Urgent Delivery

The photo looks like a scene from an Indiana Jones movie.

With a cooler suspended from a strap around his chest, a UNICEF health worker harnessed to a cable carefully pulls himself across a swift- moving river in India. Heart racing, eyes focused on his hands as he grips with right, then left, he must trust the strength of his arms, the cable and the harness to reach his destination unscathed.

Precarious? Sure. But it’s the most expedient way to deliver life-saving vaccines to children living in isolated villages beyond the opposite bank.

In the global health community, harrowing treks like this are called “the last mile.” And there’s something far more serious at stake than a fictional archaeologist’s fortune and glory.

Vaccines save an estimated 2.5 million lives each year, according to the World Health Organization. But they’re only as effective as their ability to reach people everywhere on the planet with their medicinal value intact.

Eight thousand miles from that Indian river, KU researchers help vaccines survive their journeys.

In laboratories overlooking the Research Partnership Zone in KU’s West District, pharmaceutical chemists David Volkin and Sangeeta Joshi have assembled a team of scientists with the specialized expertise to help build vaccines that are more affordable for low- and middle-income countries and capable of surviving the volatile path from manufacturer to child in vulnerable regions.

On the strength of three new research grants and a service contract totaling about $10 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Volkin and Joshi recently launched the Vaccine Analytics & Formulation Center (VAFC) within the KU School of Pharmacy. Although Volkin has conducted vaccine research at KU for a decade and Joshi for twice as long, they now are turning their team’s attention almost entirely toward advancing vaccine candidates for the developing world.

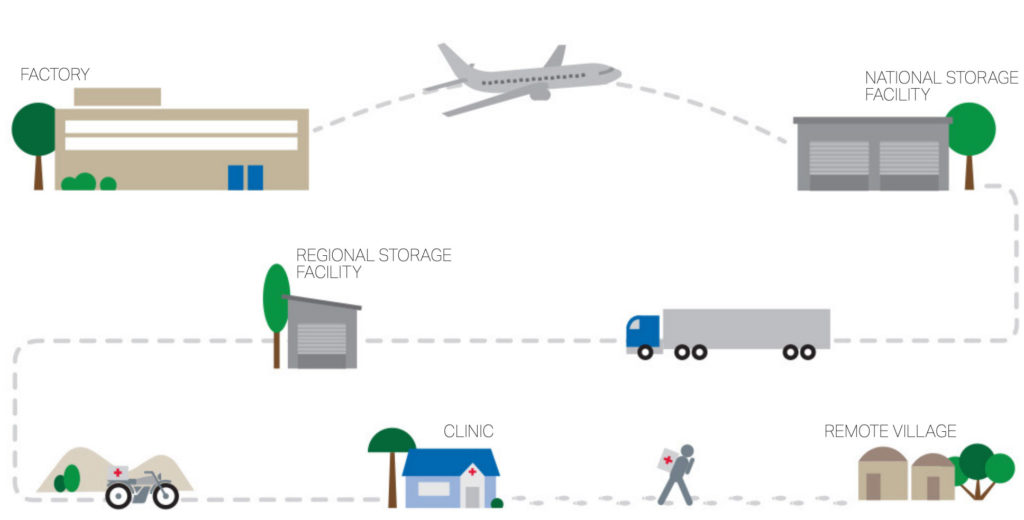

It’s a mission with unique challenges. All vaccines pass through a complex, refrigerated “cold chain” designed to preserve their immune-boosting properties during shipment and storage. But vaccines destined for developing countries must also be capable of enduring harsh conditions that might arise during “last-mile” treks across inhospitable terrain. The resolute workers who brave those journeys and the children who stand to benefit from their deliveries inspire KU’s scientists to do their best work every day.

“We certainly feel a sense of urgency because the vaccine candidates we study could have a large impact on public health,” says John Hickey, c’06, PhD’11, scientific assistant director at the VAFC. “But we must be systematic, thorough and guided by sound science. The safety and efficacy of these vaccines are paramount.”

When the global health community launched the Decade of Vaccines, it envisioned a world in which all individuals and communities could enjoy lives free from vaccine-preventable diseases by 2020. Despite great strides—including a 73% reduction in measles deaths and the near-eradication of polio—one in five children worldwide are still missing routine vaccinations, resulting in about 1.5 million deaths each year.

To help meet this urgent need, the Gates Foundation builds coalitions to move promising new vaccines from discovery to delivery. KU scientists at the VAFC are among the catalysts in that pipeline.

“We’re here to facilitate translational medicine,” says Volkin, the Ronald T. Borchardt Distinguished Professor of Pharmaceutical Chemistry and principal investigator on the VAFC’s Gates Foundation awards. “When one of our partners discovers a new vaccine candidate, we address analytical and formulation challenges to ensure the vaccine will remain stable and potent as it advances from the laboratory into clinical trials.”

Oluwadara Ogun, Ying Wan and Ozan Kumru work in the VAFC lab to analyze and formulate vaccine candidates. Photo: Dan Storey

VAFC scientific staff, postdoctoral fellows and graduate students are working on dozens of collaborative projects supported primarily by the Gates Foundation and its global partners, including nonprofit organizations, academics, biotech companies and developing countries’ vaccine manufacturers. The three most recent Gates Foundation grants provide directed funding to KU to evaluate:

• New formulations of HPV vaccines that contain multiple doses in a single vial and remain potent during long-term storage. Special preservatives extend the shelf life of the vaccines so they can protect many children.

• Various formulations of a rotavirus vaccine candidate that could be added to existing pediatric combination vaccines. Combination vaccines take two or more vaccines that could be given individually and put them into a single shot, reducing cost and the number of health care visits required.

• Low-cost formulations of immune-stimulating antibodies that can be delivered orally to protect against infectious diseases, a strategy known as passive immunization.

The life-saving benefits of KU’s work on these and other Gates Foundation projects will be compounded by the organization’s open-access policy.

“I really like their commitment to publishing research results,” says Joshi, director of the VAFC and co-investigator on the grants. “The hope is that once our work is shared with the scientific community, other researchers and developing countries’ vaccine manufacturers can build on our results to produce vaccines that meet the needs of specific countries and regions.”

On the third floor of KU’s Multidisciplinary Research Building, modern finishes and natural light connect VAFC laboratories, offices and common areas. The bright, open environment mirrors the collaborative spirit of the scientists working within the space to help people around the world.

“Given the complexity of analyzing and formulating vaccines, all aspects of our work are collaborative,” Hickey says. “Teams can range from two or three scientists to half of our group. We all have unique backgrounds that coalesce not only to design and execute a study, but also to strengthen and expand all of our knowledge.”

The foes in their quiet battle—microscopic pathogens that spawn diseases like rotavirus, polio and tetanus—elude the naked eye. But they’re not invincible. Vaccines weaponize our bodies against infection by introducing a weakened or killed form of the disease-causing virus or bacteria. Healthy immune systems respond by developing antibodies—an army of biological soldiers ready to mount a defense anytime they encounter the invader in the future.

Scientists in the VAFC are the drill sergeants in this scenario, running vaccine candidates through an analytical and formulation boot camp:

• They start by reviewing published research and conferring with collaborators about their experience with the candidate.

• Next, they examine the vaccine from every possible angle, running it through state-of-the-art instrumentation in the lab to understand its structure and determine how it might respond to stresses commonly encountered during manufacturing, storage, handling and administration.

• Then they synthesize all of that knowledge to design and implement a formulation strategy. That often involves adding an adjuvant—an ingredient that boosts the body’s immune response to the vaccine—and any number of excipients—substances that help stabilize the vaccine at the molecular level.

• For vaccines intended for the developing world, the KU team also emphasizes formulation approaches that can lower costs, including compatibility with other vaccines (combination vaccines) and preservatives (multi-dose vaccines).

• Manufacturers then use those formulations to ensure that every vial of vaccine they produce is identically safe, potent and stable.

A complete characterization and formulation project for a new vaccine candidate might take several years of rigorous, daily attention.

“Every day is a new challenge, a new discovery,” Hickey says. “And that’s what drew me to science in the first place.”

Through its specialized work, the VAFC is preparing a new generation of scientists like Hickey with the interdisciplinary expertise to help improve the lives of people who have the most urgent needs and the fewest champions.

John Hickey and Kaushal Jerajani, g’20, are among VAFC scientists collaborating with global partners to advance vaccine candidates for the developing world. Photo: Dan Storey

“Training of students and postdoctoral scientists is a key role for us,” Volkin says. “We’re working in a highly specialized field. You don’t get a college degree in how to make vaccines. You first must have a really good science background, and then you must learn how to apply it to this field.”

While earning his doctorate in microbiology at KU Medical Center, Ozan Kumru, PhD’11, took a vaccine development course on the Lawrence campus, learned about the VAFC and successfully applied for a postdoctoral fellowship.

“I underestimated how much I would learn and the challenges of vaccine formulation and development,” says Kumru, now a scientific assistant director at the VAFC. “Our work with the Gates Foundation is very rewarding to me personally. I feel like we are really making a difference in helping to bring stable vaccines to the developing world and saving lives.”

Formulating vaccines requires knowledge from various disciplines, including cell biology, microbiology, virology, genetics, immunology, pharmacokinetics, biochemistry, biophysics, physical chemistry, pharmaceutical chemistry, and more.

“When you first join the lab, the learning curve is steep,” Kumru says. “I’ve received more training than I ever thought possible, and I’m constantly learning more. There are new challenges in every project, and technology is rapidly evolving. It really is an exciting time to be in science, and I feel like I have found my calling.”

The VAFC’s growing relationship with the Gates Foundation also includes a $17.6 million Grand Challenge Grant awarded in 2017 for a collaboration with University College London and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Through this ongoing project, Ultra-low Cost Transferable Automated (ULTRA) Platform for Vaccine Manufacture, the researchers are attempting to standardize the development of new recombinant protein vaccines and produce them for less than 15 cents a dose.

After that, it could still be a decade or more before a new vaccine travels “the last mile” to children in the developing world —for good reason.

“Vaccines can take up to 20 years to develop before they are ready for widespread use,” Volkin says. “Vaccines are very difficult to produce at a large manufacturing scale, and vaccine clinical trials require very extensive, multiphased testing to ensure their safety and efficacy.”

The long road to vaccination

Vaccines must be kept between 35 to 45 degrees from the factory to some of the most remote places on earth.

For Volkin and Joshi, who have made this type of vaccine development the top priority of their professional careers, every milestone achieved is exciting.

“We’re advancing new vaccine candidates at the VAFC,” Joshi says. “Hopefully one of these projects will lead to a new vaccine for use in the developing world. That would be a dream come true for me.”

“One thing I’ve learned is the importance of finding purpose and meaning in your work,” Volkin says. “After spending 20 years as an R&D scientist in the vaccine and biopharmaceutical industry, I came to KU 10 years ago to develop a research program for something I really feel passionate about, and I have found it with our new mission here at the VAFC.”

A similar passion fuels research and teaching throughout KU’s School of Pharmacy, says Dean Ronald Ragan, p’84, g’97, PhD’98. Several years ago, the University asked each school and department to answer, in one sentence, the question, “Why do you do what you do?” The School of Pharmacy’s response? “Because the discovery and delivery of effective medicines enhance and extend lives.”

“I’m struck by how accurately and powerfully that statement describes the work that Dr. David Volkin, Dr. Sangeeta Joshi and the entire VAFC team do each and every day,” Ragan says. “We’re proud of the positive impact they have on the world, and particularly on those places that are not as fortunate as we are here in America.”

—Paget, c’99, g’01, is director of external affairs for the KU Office of Research.

19.4 million infants in need

In 2018, an estimated 19.4 million infants worldwide were not reached with routine immunization services such as three doses of DTP vaccine. About 60% of these children live in 10 countries:

Angola

Brazil

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Ethiopia

India

Indonesia

Nigeria

Pakistan

The Philippines

Vietnam

Source: World Health Organization