The Storyteller

Devin Scillian anchors the evening newscasts on WDIV, Detroit’s top-rated local TV news broadcast for nine years running. He has won the Edward R. Murrow Award, one of broadcast journalism’s highest honors, four times; covered eight Olympiads; and broadcast live from Red Square, the Vatican and the Forbidden City, among other iconic international locales. He has interviewed many political figures and celebrities in a career that dates back to the mid 1980s, when he got his first anchor job on a Topeka station while still at KU. He’s been around.

But to hear Scillian, j’85, tell it, one of his greatest professional thrills came in a Michigan shopping mall, when a high school kid whose name he didn’t know walked up and dropped a rhyme on him that blew his mind.

If there were a checklist of anchorman attributes (and maybe there is, come to think of it—a fuzzy nth-generation photocopy tacked to the bulletin boards of news directors across America) the 57-year-old Scillian would seem to tick every box. Confident smile. Square jaw. Great hair. Just-right mix of gravitas and avuncular good nature. But he also possesses a disarmingly goofy laugh, the subtext of which seems to be Can you believe it, man?, and a reputation for humble genuineness. His news director calls him “a man of many layers, and on all those layers he performs very highly, which is what makes him so special.”

His old professor says he was “a big-timer but he never acted big time; he was just a guy and he still is.” The reputation rooted early and blossomed throughout his career; the laugh he dispenses generously—especially when discussing the myriad interests that fill his off-camera hours.

Scillian is an accomplished country music singer and songwriter, appearing frequently at festivals and music venues across Michigan with his band, Arizona Son, until COVID-19 slammed the lid on honky-tonkin’. He has recorded three albums of his own songs, and has mastered an impressive catalog of standards: Last spring, when Michigan became one of the first states to lock down in response to the pandemic, Scillian began posting a new performance every day to Instagram (where his bio reads “Journalist, author, musician … It’s complicated.”), going seven weeks without repeating himself.

A high-school theatre geek who came to KU from Junction City on a theatre scholarship, Scillian has landed cameos in several movies, including Wes Craven’s “Scream 4,” where his ease at handling a last-second addition to his lines during a 3 a.m. shoot impressed the director so much that the Master of Horror later sent Scillian a bottle of wine in thanks. He also maintains a recurring role anchoring the “Breaking News” skits on “The Ellen Degeneres Show.”

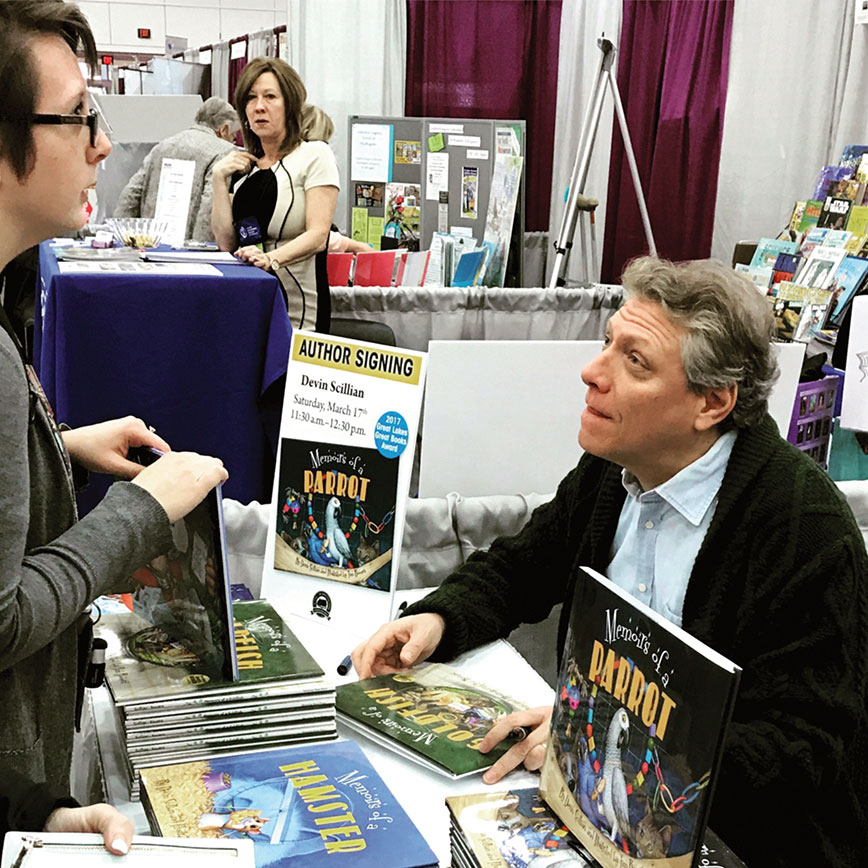

After spending years trying to publish a children’s book—he wrote his first while a KU student—he broke through in 2000 with his second effort, Fibblestax, the charming tale of a mythical boy known as “the one who gives a name to every single thing. If not for him we couldn’t talk. Or read, or write or sing …” The book, a feast of rhyme and wordplay, grew out of Scillian’s love of language, and it was followed by 19 more books for kids, most recently Memoirs of a Tortoise, part of his popular series that started with Memoirs of a Goldfish.

Scillian visits schools not only to share his books and stories, but also to inspire kids to think about the written word. He asks students if they are good writers. Most say no. Then he asks if they are good storytellers. More hands this time. “If you’re a good storyteller,” he tells them, “you’re already a good writer.”

During one visit he shared with his young audience one of his favorite words: sprocket.

“I said, ‘I just love the sound of it,” he recalls. “And one little girl held out her necklace and said, ‘I’m wearing a locket.’ Another kid pointed out, ‘That rhymes with rocket.’ In about two minutes, we’d come up with, ‘I had a sprocket in my pocket. I locked it in a locket. I tightened it with a socket. I launched it in a rocket. I used a stopwatch to clock it. And boy did that thing go.’

“We took a word that we liked, and built this whole world around it.”

A decade passes and one day Scillian is walking through a shopping mall. A high school kid approaches.

“He repeats that full rhyme to me!” he says, his laugh tinged now with delight. “From that night! I was absolutely blown away.

“Teachers get this experience all the time, but most of us who don’t teach don’t get to see the lights come on that way. Not every kid is going to turn out a writer; not every kid is going to be all that interested. But the ones that you can spark their imagination, I think that’s really worthwhile.”

People see the Hollywood cameos, the kids’ books and country tunes, “and they think I’m all over the place,” Scillian says. But the thread connecting these disparate interests is apparent to him.

“They’re all sort of wrapped up in storytelling,” he says. “I really like a good story. The ones that I tell when I’m doing a documentary or reporting on the news—obviously I work in nonfiction then—and when I turn to music and storybooks it’s a little more free-flowing, wherever I want it to go. But it all boils down to trying to tell a good story.”

As soon as he arrived on Mount Oread, Scillian jumped straight into acting.

“One of the things I really loved about the theatre was the pressure of performance,” he says. “I really enjoyed that part.”

On top of acting in University Theatre productions, he took a few broadcast journalism classes and got a DJ gig at KJHK, an early Sunday morning shift. The studio had a small TV that students were supposed to use to check time and temperature.

“One morning I’m looking around while the music is playing, and I realize there’s been an attack on the American Marine base in Beirut,” Scillian recalls. On Oct. 23, 1983, 220 U.S. Marines and 21 other military service members died in a truck-bombing that was later traced to Hezbollah. It was the deadliest attack on U.S. Marines since Iwo Jima.

“I have no idea why I thought my audience, listening to Dead Kennedys or whatever I was playing, needed to know what was going on in Beirut,” Scillian says, “but I absolutely felt this responsibility to share what was happening.” His first break-in was breathless and panicked. “It was amateur hour,” he recalls. “But by the end of the morning I was waxing on about Mideast history and political science. I think it really whetted my appetite for the fact that in television news the script changes every day.”

He came to realize that a reporter was really a writer, “and that was what I loved to do, too,” he says. He had taken a couple of English classes with professor Alan Lichter: children’s lit and creative writing. Assigned to write a children’s story, Scillian reworked one he’d written in high school. Lichter photocopied the story for the entire class to read.

“He looked at me and said, ‘You could get this published tomorrow.’ Now, he was wrong,” Scillian says. “I wasn’t able to get it published tomorrow. But what he did is he instilled in me this idea that maybe I had a talent for writing.”

His first encounter with the high-wire act of breaking a developing story that morning at KJHK brought “a number of my passions together,” Scillian says: The performance pressure he relished, the need for precision and clarity in language, the thrill of telling a story that needed to be told.

He switched his major to journalism but stayed active in theatre, appearing in a dozen productions before graduating. The summer of his junior year he landed an internship at WIBW in Topeka, and parlayed that into a job as the anchor of the Saturday noon newscast. From that moment on, as he moved into full-time broadcasting in larger and larger markets—Decatur, Illinois; Tyler, Texas; Oklahoma City—he sought jobs that guaranteed time at the anchor desk and time to report stories in the field. Gradually, Scillian says, “I became very intoxicated with writing the first draft of history every day.”

Scillian’s reporting has taken him to Olympiads (2016 in Rio, right), Capitol Hill (with U.S. Rep. John Lewis, above) and world capitals (Moscow, left). “’I’ve been extremely fortunate to interview presidents at the White House and more than a few celebrities over the years, but the interviews that have really stayed with me are much lower in profile.” Among them: “A lovely and genteel old fellow whose name I have forgotten on the streets of Cambridge, England. After talking about the excitement of the Olympics coming to England, he told me, ‘Well, it’s been lovely chatting with you but I’m afraid it’s beginning to impinge on the cocktail hour.’ It was 11 in the morning.”

By 1995, Scillian was ready to step up to a top-15 market; that spring he signed a contract with WDIV to join the Detroit station as a reporter for a year before moving into the slot held by Mort Crim, the legendary news anchor (and the inspiration for Will Ferrell’s character Ron Burgundy in “Anchor Man”), who was planning to retire.

On April 19, Scillian was in bed at 9:02 a.m. when a massive boom rocked his neighborhood, more than 10 miles from downtown Oklahoma City.

His wife, Corey, ran outside, as did most of the neighbors. “We were sure it was right in our neighborhood, because it was so loud and so concussive,” Scillian says. “And of course it turned out it was all the way downtown.”

A truck bomb rigged with 7,000 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer and diesel fuel had been detonated, destroying the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building and killing 168 people, including 19 children in a day care inside the complex.

Scillian spent 14 hours on air that day, breaking the shocking news of what is still the deadliest incident of domestic terrorism on American soil. NBC piped the KFOR feed to a disbelieving nation, and CNN spread it around the world. The news director at WDIV left Scillian a voice message: You’re already making your debut in Detroit; we just didn’t know it was coming so soon.

Max Utsler, then on leave from KU’s William Allen White School of Journalism, where he was an associate professor in the broadcasting track, was working at KPNX-TV in Phoenix.

“The way that coverage unfolded that day, he had to be a reporter, he had to know what questions to ask to advance the story, and he did that flawlessly,” recalls Utsler, now retired. “To me, that’s one of the real positive things about him. Some folks get a case of what we call ‘anchoritis,’ and they start thinking they’re TV stars instead of journalists. He never went that route at all, and it really showed in Oklahoma City.”

The traumatic, deeply emotional experience, Scillian says, “was the worst day of my life, and yet it also turned out to be a very powerful sermon for me on the potency of not only journalism, but love.”

After 10 years in the news business, Scillian admits he’d “gotten a little cynical” about the world.

“I’d been to some awful places. I’d been to L.A. to cover the gang problem. I’d been to Haiti, the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, where little kids the ages of my kids were playing in sewage in the streets. I’d been to the Mideast, where hatred seemed to be baked into the stones. And it’s still crazy to me that the worst day of life turned me back into an optimist. Because the lesson for me of Oklahoma City is, for every one or two truly evil people there’s a million more ready to drop everything and run to help people they don’t even know. And that’s a world I can live in.”

It’s a lesson he draws on a lot these days, when deep polarization has poisoned the public sphere and his chosen profession is under attack from the highest levels of government. Practicing journalism now, Scillian says, using a memorable phrase coined by a friend, “is like being stuck in the dunk tank on a psychotic midway.”

In late March, as WDIV cut away from live coverage of a White House coronavirus briefing in which President Trump accused the media of writing “fake news” about the pandemic in hopes of damaging his reelection bid, Scillian felt moved to offer a defense of his fellow journalists.

The Detroit Free Press called it “a rare step” by an anchor with “a solid reputation for delivering the news with fairness and impartiality.”

“It’s dispiriting, because I’m telling you right now American journalists are working in insane conditions to try to bring you the latest in a situation that is unprecedented for all of us, and I’ve never been prouder of the people in this building, of my colleagues at papers and television stations and radio stations all over the country,” he told viewers. “So regardless of your support or nonsupport for the president, I’m begging you not to tolerate attacks on a lot of journalists right now who are working their tails off.”

“Fabulous,” says Kim Voet, WDIV news director. “Absolutely fabulous. I stood up and clapped in the newsroom. I really did. I think that journalism has been under fire, and I applaud him immensely for standing up for journalists that day.”

Scillian’s hard-earned credibility gave his words more punch, Voet believes.

“He’s always been somebody that never lets his opinion get out there in the way of a story, and I applaud him for that too. What made his comments that day even more poignant and more powerful is that he is not someone who puts his opinion out there. If you listen to the comments that he said and the way he said it, he wasn’t yelling from a mountaintop; he wasn’t preaching. The message he conveyed is one that is and has been sung by many true journalists for quite some time. People like Devin are the epitome of true journalism.”

Scillian followed up with an essay more fully explaining his thinking on the topic, while also confessing his ambivalence at sharing an opinion on the air.

Seven months later, that ambivalence lingered.

“I still believe, just as I was taught at KU, in the idea of a neutral journalist,” Scillian says. “I tell people all the time, ‘My job is to be an aggressive Switzerland every day.’ I work really hard to control my temper and my emotions. But that moment, when I was watching our newsroom and newsrooms all over the country working in such extreme circumstances, to hear reporters being disparaged when the flow of reliable information to me seemed so critical as the pandemic was breaking out and people had to be able to trust what they were being told on television, on radio, in the papers—I thought that was a poorly chosen moment to go after reporters.”

The response from readers was better than expected, he says, with even some supporters of the president agreeing that this was not the time to wage war on the press. Similarly, the response to the Sunday morning public affairs program he started, “Flashpoint,” typically runs about 50-50.

“Half the people write to complain they can’t understand why channel 4 puts a liberal like me on the air every week, and the other half can’t understand how an unabashed conservative like myself can look in the mirror every day,” Scillian says.

“I’ve always thought that’s a fairly good sign; if I’m an equal opportunity offender, maybe I’m doing something right.”

Scillian remembers graduating from KU and thinking, Now I have to pick one thing to do for the rest of my life?

“I was a little despondent because there were so many creative things I like to do and explore,” he says, laughing this time at his younger self.

“I don’t know why I thought that. It’s been really gratifying to realize that of course you don’t just do one thing with your life, and I could continue to explore all these other passions of mine.”

Among his 20 children’s books, One Kansas Farmer and S is for Sunflower, both written with Corey, d’85, g’86, a ceramic artist, are particularly meaningful. “That was really, really fun to work on those together,” Scillian says. Special too is Memoirs of a Goldfish, which won several kids’ choice awards and, as a Michigan Reads selection, was read by every fourth-grader in the state. While Memoirs of a Tortoise, published in May, tackles a serious topic—the death of a long-lived pet’s owner—for the most part the books offer a break from worldly cares, Scillian allows.

As the run-up to the November election raised the stakes (and the temperature) on our political differences, an urge to step away from the carnival, if only for a little while, was understandable. Many must have it. But when the midway is your beat, taking that break is harder—and perhaps doubly important.

In that spirit Scillian started posting songs to Instagram during lockdown from his Grosse Pointe Park home, singing and accompanying himself on guitar, piano, mandolin, ukulele. Urged on by his 5,600 followers and fans who sent requests, he continued the Quarantine Interludes, as he calls them, daily for two months and intermittently after that.

“What it did for me every day to think about something else and pour some thought into a guitar or piano was such a great refuge,” Scillian says. “It really turned out to be an oasis. And books are the same: Anytime that I can kind of run to my creative space it usually feels like a bit of a vacation.”

On nearly every school visit, Scillian finds himself in the library, where he seeks out his favorite childhood book, My Side of the Mountain, the classic adventure tale by Jean Craighead George.

“I always go look for My Side of the Mountain, just because I want to make sure it’s still there,” he says. “I don’t need to read it. I have it at home. I’ve practically got a lot of it memorized. I just want to touch it. I think that’s one of the things I’ve always appreciated and come to love about books is their permanence. I’ve always stayed very, very attached to the books that meant so much to me when I was a kid.”

After Scillian started writing his own books, he received a letter from a father. His son’s favorite book was Cosmo’s Moon, which Scillian published in 2003.

“He wrote to tell me that they had read it every night before bed for six months. I wrote it and I don’t think I could read it every night for six months,” Scillian says, again with the laugh. “I just stopped to think, ‘Is that little boy one day going to go into a library when he’s older and look for Cosmo’s Moon just because he wants to make sure it’s still there?’ That’s a feeling that kind of overwhelms me.”

Not the cranked-up-crazy-carnival brand of overwhelm, you understand. More like, Man, can you believe it?