The Art of Science (and Vice Versa)

The question was ill-conceived, ignorant and irritating, and Leonard Krishtalka was right to swat it aside. It wasn’t even a question, exactly, but more like a disjointed observation that somehow escapes the brain and, in that eternal split-second where regrets are hatched, becomes words that can’t be taken back.

Under the leadership of Krishtalka, its director, the KU Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Institute in summer 2017 was preparing to launch an extensive renovation of Dyche Hall’s uppermost research and storage spaces and its weather-battered limestone exterior, including the famous grotesques. It would not be cheap to remove, preserve and replace each of the century-old carvings, so—as the quasi-question went—even making the effort was laudable.

The building’s exterior art, after all, had nothing to do with the science happening inside, and it’s not as if brilliant and dedicated researchers and educators couldn’t do their jobs just as well, regardless of their building’s adornments, right?

Krishtalka drew a deep breath before summoning his response.

“I could not,” he replied coolly, “disagree more.”

He explained that, just as saintly statuary is mounted atop churches and cathedrals as protectors of the faithful and messengers of peace, Dyche Hall’s grotesques serve similar roles in protecting and encouraging the life of the mind.

“Perhaps the grotesques were meant to be a symbol of co-existence with nature, that we have inherited the contract to sustain the natural world in a smart fashion.”

Science, Krishtalka explained urgently, is not independent of art and art is not independent of science; each is lesser without the other. He cited University Distinguished Professor Town Peterson comparing historic images of Mexican landscapes with his own photographs to study erosion, encroachment and habitat loss; great naturalists who brought dazzling sketches and paintings of flora and fauna from exotic lands; military surveys of little-explored frontiers that always included artists and photographers; depictions of fantastic and mythical beasts created by painters working from descriptions provided by explorers who had ventured around that mysterious far bend.

“Go all the way back to the cave paintings,” Krishtalka continued. “Art and its role in spreading knowledge about the animals and spiritual systems dates back to our very beginnings.

“What we do here at the Biodiversity Institute is an act of creating knowledge through research. The grotesques, their carving, the architecture of the building, is all a fantastic act of creation, and the act of creation in sciences and art is inseparable.”

As it happens, a brilliant expansion on Krishtalka’s memorable riff is now playing out just down the Hill from Dyche Hall: the Spencer Museum of Art exhibition “knowledges,” within which any lingering doubts about the necessity of intertwining creative arts and rigorous research are forever dashed.

Under the leadership of Marilyn Stokstad Director Saralyn Reece Hardy, c’76, g’94, the Spencer Museum of Art has over the past decade dedicated energy and resources toward the same sort of passions Krishtalka expressed when it was suggested to him that art outside wasn’t really so necessary to science inside. Research in the sciences and humanities is integral to art, Spencer staff contend, and art, in turn, helps researchers find new views into the worlds they investigate.

“The Spencer Museum is an art museum that’s embedded in a research university, and so we should be serving the research community,” says Joey Orr, Andrew W. Mellon Curator for Research. “But what happens when you bring a bunch of different kinds of researchers together is that inevitably you start to talk about not just the subject matter, but how it is we produce knowledge in the first place.”

Launched in 2015 with $487,000 from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Spencer’s Integrated Arts Research Initiative (IARI, pronounced “are-e”) sought to create programming that would bring KU researchers into the life of the museum. Since 2016, IARI has awarded fellowships to nine KU faculty members, three graduate students and nine undergraduates across 14 departments.

Reece Hardy in 2016 hired Orr, then the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and he began work here in early 2017. Orr immediately began focusing IARI’s activities around yearlong themes, such as ecology and social history, and, along with identifying research fellows from across KU, he also invited outside scholars and the Lawrence community to participate in discussions, lectures and exhibitions.

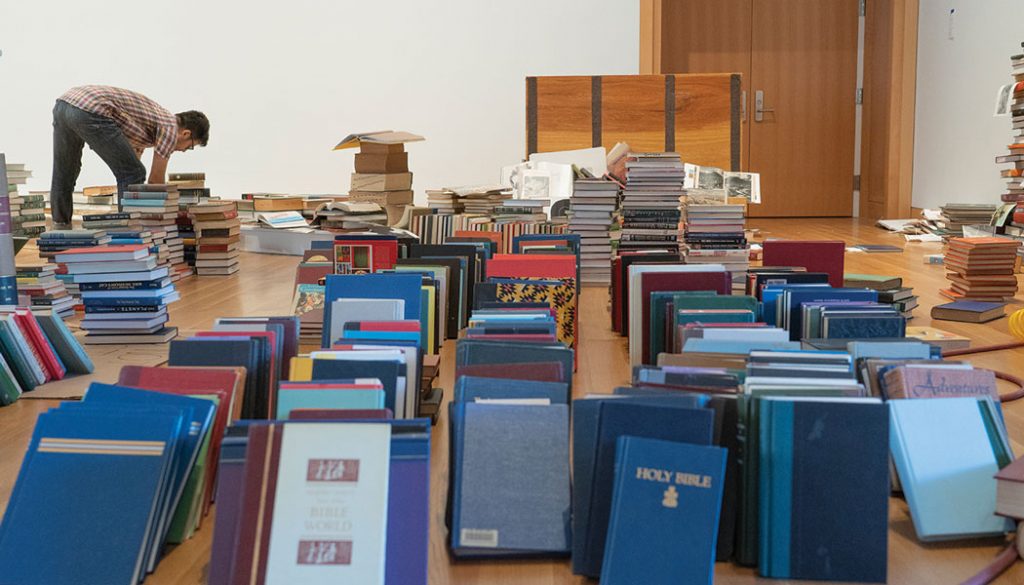

Artists Andrew Yang (left) and Assaf Evron prepare “knowledges” installations.

Psychology professor Glenn Adams used his 2018 fellowship, for instance, to explore “how knowledge institutions can prompt or promote civic engagement.” Working in conjunction with the Haitian history exhibition “The Ties that Bind,” Adams hoped to gain deeper appreciation for how a museum can enhance appreciation for cultural diversity.

“It is one of the more useful ways to raise some of the issues,” Adams says of readily accessible visual imagery. “These are difficult concepts, and the museum can be a place for people to see that.”

IARI’s string of promising successes led the Mellon Foundation in July to award the Spencer Museum an even richer grant, this time for $650,000 over five years. This semester’s IARI-affiliated exhibition, the sprawling “knowledges,” was funded with grants from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts.

“The funding that they’re getting from the Mellon and the Warhol, of course those are two highly prestigious funding sources for academics and for art,” says Andrew Yang, associate professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, whose brilliant artistic expressions of fundamental scientific concepts in earth and life sciences are among the highlights of the current exhibition. “The funding environment right now, especially for the arts, is especially tight, so the fact that they’re able to get that funding renewed is an amazing testament.

“If you’re not hitting the 1 percent in this funding environment, you’re not going to get the grant, so it speaks volumes about what they’ve developed here.”

“knowledges,” which opened Aug. 24 and runs through Jan. 5, explores four research themes previously featured in IARI programming—data visualization, ecology, social history and immigration—with contemporary installation art by Yang; 2019 Guggenheim Fellow Fatimah Tuggar, currently based in Kansas City; Brooklyn artist Danielle Roney; and photographer and sculptor Assaf Evron, of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Exactly as Orr and his Spencer colleagues intended, “knowledges” is complicated and thought-provoking while also offering playful joys of visual delights. Orr recounts that growing up in Atlanta, he had no exposure to contemporary art, so he keeps in mind good intentions for neophytes and newcomers.

“It wasn’t until I was in my 20s when I finally saw something and realized what artists are doing and what is possible,” Orr says. “So my hope is that there’s a lot of room here for different kinds of experiences. If you want to come in here and have a serious discussion about immigration or start to think about ecologies and recycling and climate science, all of that is possible. But it’s also possible just to come in and be in the space with the kind of work that you may or not have a lot of experience encountering.

“If you know nothing about the idea behind the exhibition and are just interested in walking through the museum in some free time, you’re probably going to have a pretty good visit.”

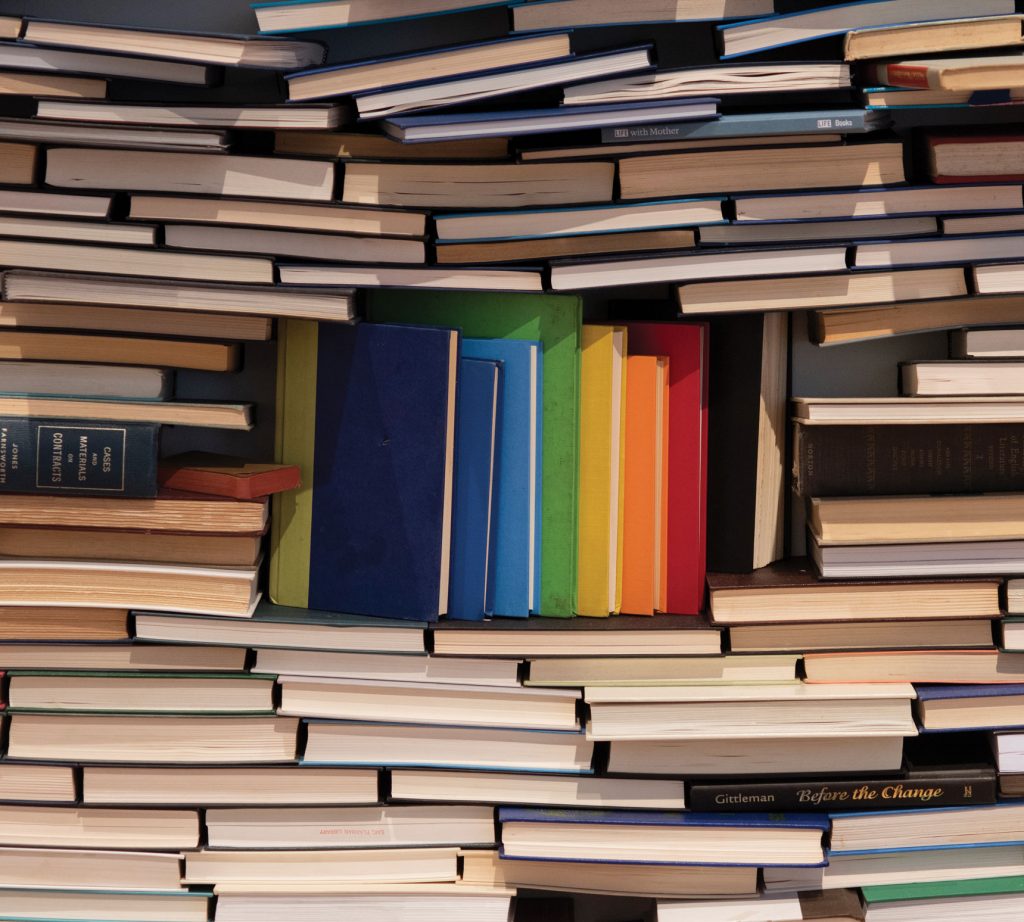

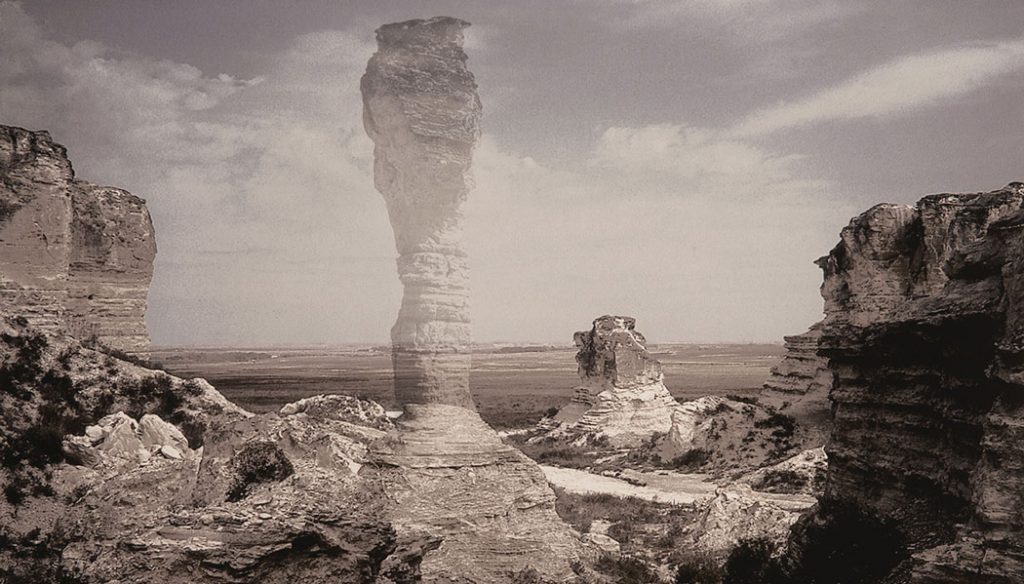

Rex Buchanan, director emeritus of Kansas Geological Survey, first encountered “knowledges” during the preview opening for Friends of the Art Museum, and he immediately immersed himself in Andy Yang’s “bibliographic rock face” of discarded books—each page of which represents 10,000 years, or the span of human civilization, in Earth’s 4.54 billion years—titled “Deep Time Library & Archive,” and a pair of installations depicting Kansas landmarks Cobra Rock and Castle Rock.

A “knowledges” installation, completed in the Sam and Connie Perkins Central Court.

Yang, who earned a biology PhD at Duke University, made three research trips to KU before the installation, and during one of those trips he met retired geological survey photographer John Charlton, c’75, g’83, and found within Charlton’s archives images of Cobra Rock and Castle Rock before and after the iconic limestone formations collapsed. Yang ghosted the before-and-after images atop one another, and hung those photographs on the wall next to his bibliographic re-creations.

Buchanan, a Kansas Public Radio essayist and Kansas Alumni contributor, delighted in sharing nomenclature: “The technical term for those spires is ‘hoodoo.’ Cool word.”

He was impressed by the ghosted images, noting that the typical method for comparing such images is to hang them side-by-side, with the viewer’s eyes darting back and forth, and he admired the way “Deep Time Library & Archive” depicts stratographic layers of geologic time.

“I think it’s a real interesting idea,” Buchanan says of an exhibition melding arts and geology, “because we all have these silos that we live in. Historically, that connection was very close. Before the days of photography, geologists were famous for being really good sketch artists, and it’s just as applicable in the biology world, where people have drawn specimens for years and years and years.”

Impressing the director emeritus of Kansas Geological Survey within the exhibition’s opening moments: a promising start.

Yang’s installations for “knowledges” also drew on research and artifacts from the Biodiversity Institute’s Paleobotany Collection, KU Recycling, Spencer Research Library and the Lawrence Public Library, and he also delights visitors with depictions of his daughter Stella’s “stoichiometry,” or relative quantities of substances within a whole, at birth and as a 40-pound 7-year-old. For the sculpture of Stella’s bodily makeup when she was born, Yang used such natural ingredients as water, rock sugar and oyster shells; after her seven years on Earth, he chose plastics, fossil fuels and fertilizers, all of which she’d been exposed to during her young life.

“When I first saw this piece,” Orr recalls, “I asked him if he felt he was reducing his daughter to a mathematical equation. He said, ‘No, it’s just the opposite. I’m trying to make the point that we have an intimate connection to the earth. We don’t have to think about 4.54 billion years as something abstracted from us; it is us.”

Evron’s installation ponders the question, “How do we take something from the world of ideas and turn it into an object in the physical world?” For “knowledges,” he translates colors that are possible on a computer screen into 3-D rocklike sculptures; if a perfect representation of a given color is a sphere, the oblong pieces Evron created from medium-density fiberboard and epoxy represent the color’s imperfect translation when moved from a computer screen to printed materials.

“My work is research based,” Evron says, “and the Spencer—especially ‘knowledges’—is a place where this kind of work that is research based can happen. It’s so-called experimental because you’re not sure where you end, but you’re confident in your way.”

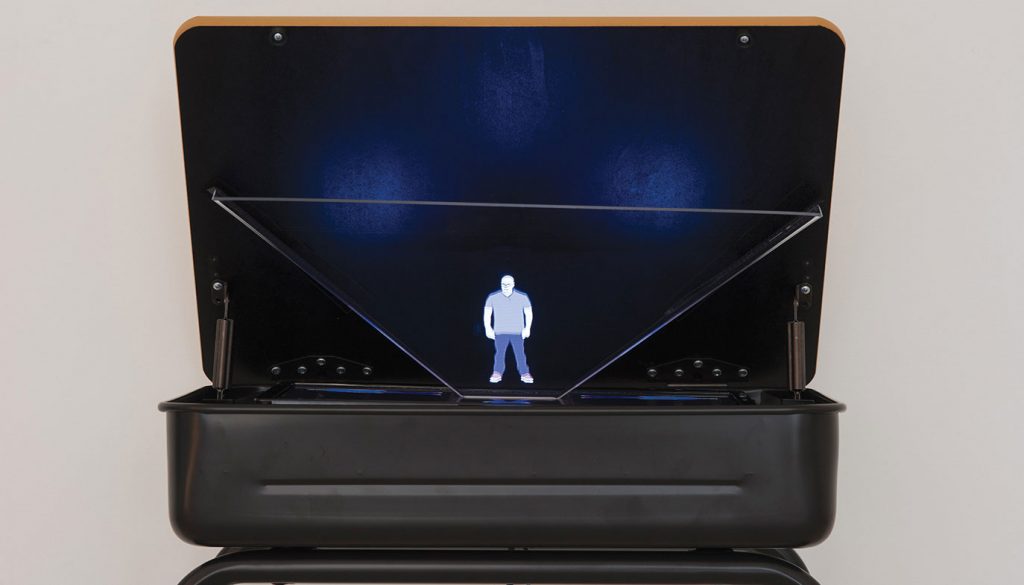

For her installation, Tuggar created eight school desks, each fitted with plastic prisms that play animated holograms of actors reading scripts Tuggar wrote about people within academia who have been harmed by racism, sexism or restriction of their freedom of inquiry.

Roney, too, explores repression, rejection and loss of freedom, but not within academia. Instead, she is inspired by immigrant communities and other marginalized people who live under constant surveillance and imminent threat of arrest and deportation. “PUBLICS,” a 12-camera sculpture of Nest security cameras, is linked to monitors accessible only by specific immigrant communities around the country that have passwords to view exhibition visitors. (A sign at the “knowledges” entrance alerts patrons to cameras in use.)

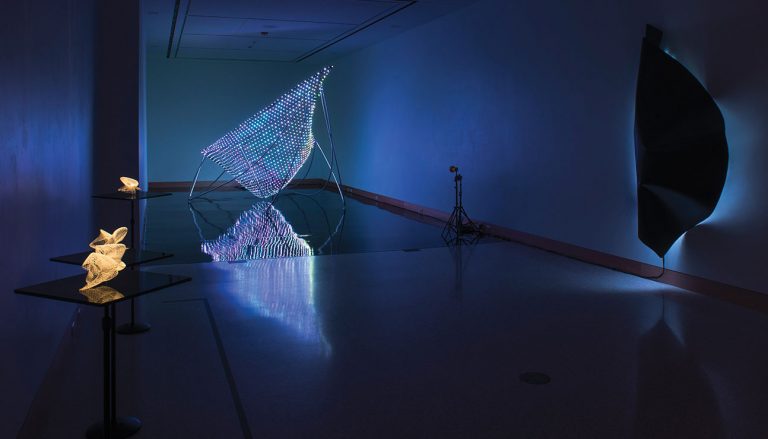

Nearby, “Strata: Bending Fields of Relation,” is a mesmerizing dance of voice-driven animation of immigrant voices playing out on LED mesh in a darkened gallery.

“This is a room that is completely silent, but it’s all about the voice, and sound,” Orr says. “She’s calling them ‘mantras.’ A chorus of a favorite song, a favorite saying, and she turns it into an animation that then dances across this LED mesh that’s resting on the sculptural structure. When you’re watching it, it is one phrase from one voice that she’s slowed down. In between the animations, the sculpture goes dark for just a moment. You are never seeing conversations or lots of voices, so this is, in some ways, its own kind of portrait.

“She describes it as radical beauty. She wants to take this population and make them beautiful and illuminated and turn them into light in the middle of the institution without divulging any information about them or making them vulnerable in any way. In a sense, she’s trying to take technology and use it for advocacy.”

When consideration is given to voices animated by happy, dancing lights—the voices of marginalized and repressed communities hounded relentlessly within a country that savors their labors while rejecting their humanity—the effect can be staggeringly overwhelming.

“That,” Orr says with a small smile, “is why we put a bench in here.”

Programming for “knowledges” will include an Integrated Arts Research Initiative Colloquium, Nov. 5-7, which in turn leads into the Nov. 7-9 Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities (a2ru) Conference, hosted by KU, which will feature presentations on creativity in research by 16 KU researchers and panel discussions with the four artists featured in “knowledges.”

During her 2017 IARI fellowship, Associate Professor Cécile Accilien, interim chair of African and African American Studies and director of the Institute of Haitian Studies, visited artists’ studios in New Orleans with Tyler Allen, c’18, in preparation for the exhibition “The Ties that Bind” and an honors seminar on connections between Haiti and Louisiana and, by extension, the entire United States.

“It has been so incredibly powerful for me to have a space to bring together my love of art with my love of literature and my love of teaching. I love the museum. When they are done the right way, as ours is, they are an incubator for an incredible body of knowledge.”

Assistant professor of design Hannah Park arrived at KU last year and quickly found her way to the Spencer. Last summer she completed an IARI fellowship, along with undergraduate design fellow Sophia Schippers, for research into “Project Lemonade,” a mobile lemonade truck Park is designing to promote mental wellness for college students.

“I think the Spencer is really acting as a hub for creative scholars who are looking for partnerships or collaborations when they are pursuing any project out of their boundaries,” Park says. “These days, a lot of problems that we have are complex. They are problems that cannot be solved by one discipline anymore. The Spencer takes this integral role in mediating and orchestrating those people who are desperate to find those collaborations.”

A few days after the opening of “knowledges,” Joey Orr, Saralyn Reece Hardy and Celka Straughn, Andrew W. Mellon Director of Academic Programs, mingle in the museum’s Sam and Connie Perkins Central Court, relaxing, chatting, sharing thoughts about the exhibition, IARI programming and what might be in store for the future.

The question is ill-conceived, ignorant and perhaps even irritating: Given the success of “knowledges,” are they prepared to continue to reach even higher, take even greater chances?

Awkward pause … which Orr finally breaks: “Have you met Saralyn?”

Reece Hardy smiles, but she perhaps seems faintly uncomfortable by the premise of both question and answer. It all feels so … serious.

“There has to be joy in the work,” she says. “There has to be a joyfulness. Even an institution has a countenance, a joyful countenance, and we have fun every day. We can’t wait to get to work.”

She ponders topics of expertise and inclusiveness and research and collegiality, and how the Spencer Museum of Art must strive to always do—and be—better.

That won’t be easy to achieve, comments one of the group, and Reece Hardy pounces.

“Easy? Who wants to do something easy? Boring!”

As ever, anything but. Not with the knowledges happening at this time within this space.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Fatimah Tuggar’s affiliation with the Kansas City Art Institute. According to Spencer Museum of Art officials, Tuggar is based in Kansas City but is not employed by KCAI.