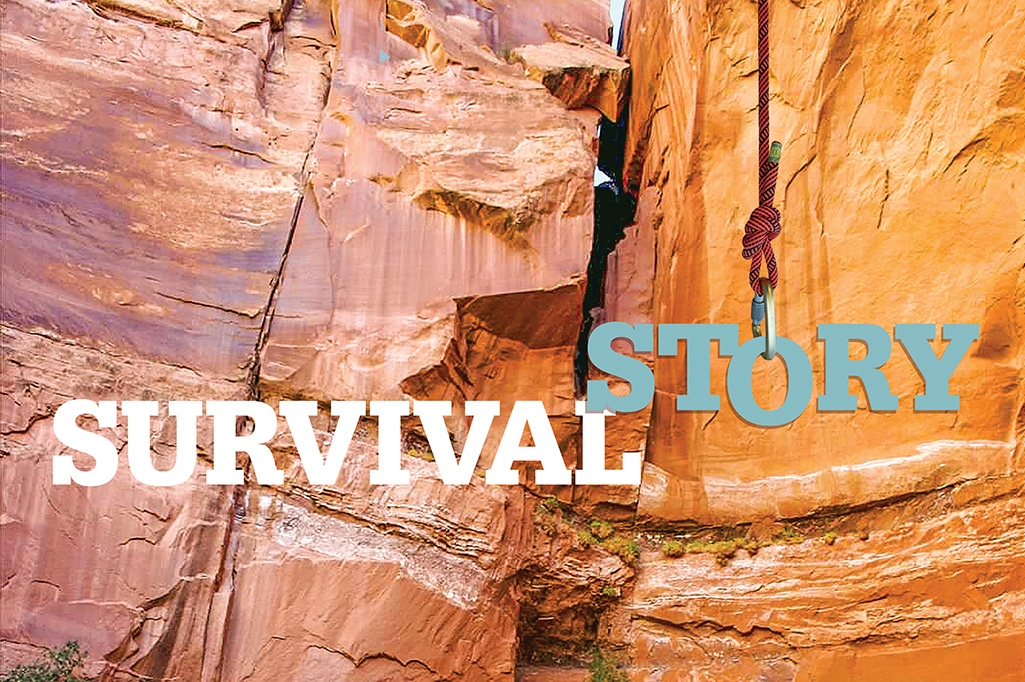

Survival Story

David Cicotello was stuck.

On a day hike in No Mans Canyon, a slot canyon in the fabled Robbers Roost area of southeastern Utah, Cicotello was in the middle of a two-stage rappel with his brother Louis. It was Sunday, March 6, 2011.

The two had hiked into the canyon’s north fork around 9 a.m., wended their way through tight sandstone rifts worn deep in the flat mesa by centuries of wind and water, and completed four short rappels—including one they set up out of an abundance of caution when a path described in trip reports as hikeable appeared more precarious than advertised. “After all,” Louis deadpanned, “I am 70 years old.”

David, then 57, “laughed like hell” at his brother’s joke.

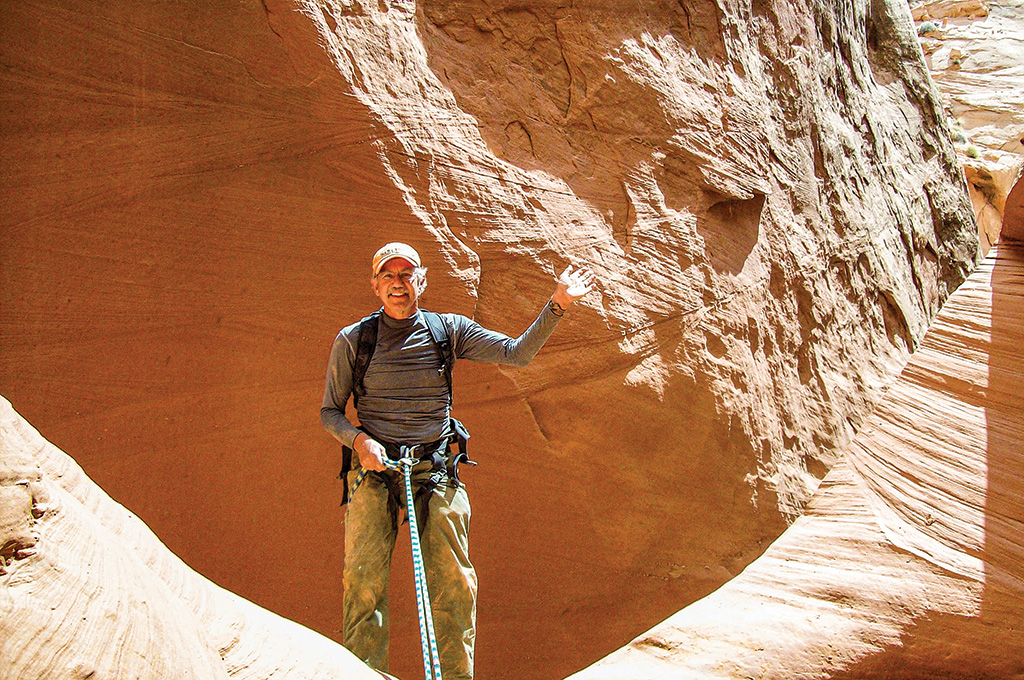

A fit, experienced mountaineer who summited most of Colorado’s 14ers before discovering canyoneering, Louis had been climbing for more than 30 years and exploring canyons for the past 13. He did three or four desert trips a year and, according to the climbers who know him best, was “meticulous” in his approach to rappelling, carefully setting the anchors that he and his fellow canyoneers used to secure the ropes for their descents. He had completed an estimated 600 rappels, many of them, in the past few years, with David. At Louis’ urging, David took up rappelling in 2006, learning first on a climbing wall near his home in Omaha, Nebraska, and later under Louis’ tutelage in Utah’s red rock country, where together they explored more than 40 canyons.

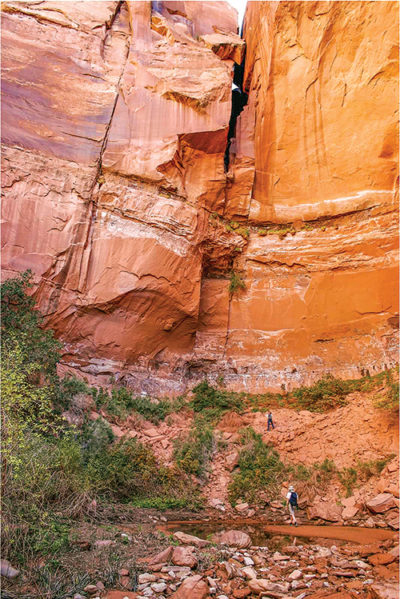

Now it was 1 p.m. and they were on their last descent of the day. Stage one was a 40-foot rappel down to a sandy ledge that was partially sheltered by an overhang from which Louis and David descended, one after the other. Once on the ledge, they pulled their climbing rope down and began rigging the second stage of the descent: a 100-foot rappel that would take every bit of their 60-meter rope to complete. They planned to eat lunch at the bottom and then begin the long hike up an old horse trail to the canyon rim, across the wind-battered mesa and back to the trailhead.

To set up the rappel, Louis started with an existing anchor point, a bolt-and-hanger secured to one wall of the cavelike ledge. To this anchor he attached a carabiner threaded with a new loop of webbing. The webbing extended nearly to the end of a 20-foot ramp that sloped steeply down to a narrow opening in the cliff face, a tall vertical slot from which the 100-foot drop began. Through a rappel ring attached to the webbing, Louis threaded one end of the climbing rope, located the rope’s midpoint and threw both strands down.

David watched as his brother clipped onto the rope and began backing down the ramp. When he reached the edge, Louis paused to warn him not to trap his hands between the rope and the rock when he came down. Then he carefully eased his body, legs first, over the edge and out of sight.

It would be the last time David Cicotello would see his brother alive.

Within seconds, he was staring in stunned disbelief as the rope carrying Louis—both he and his brother’s only means of getting off the ledge—zipped through the rappel ring, over the cliff’s edge and out of sight.

“I knew in that instant that my brother had fallen,” David says, “and taken the rope with him.”

What had begun as a six-hour hike had just become a six-day struggle for survival.

From the time he started kindergarten—the same year Louis left home for his freshman year of college—David’s big brother was an almost mythical figure in his world.

“According to our dear mother he was a legend,” David recalled wryly during Nashville Storytellers: Survival, a storytelling event in January 2019 at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center. “All A’s in high school. Valedictorian. He had read every book in our hometown library.”

When David was ready to start college, in 1971, he knew only that he wanted to leave his home state of Pennsylvania. Louis, who had earned an MFA in sculpture from Yale and was teaching at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, suggested KU. David spent weekends at Louis’ house, endlessly sanding the large Plexiglas sculptures his brother was creating. Louis took him to his first Grateful Dead show, his first Asian restaurant. “At that time, I was in awe of him,” David recalls. “That was really our first period of intense bonding.”

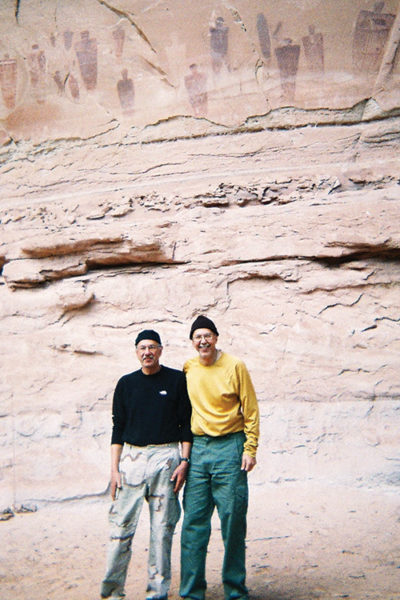

The second came decades later in the Utah desert. By then David, c’75, g’77, was working at a college in Nebraska, Louis in Colorado. They’d grown apart. But starting in 2000, on trips with a third brother, Carl, they fished and hiked and sought out remote sites that featured the ancient rock art that fascinated them. Over time, Carl focused more on the art and Louis shifted to technical climbing and rappelling, recruiting David to join him on his desert adventures.

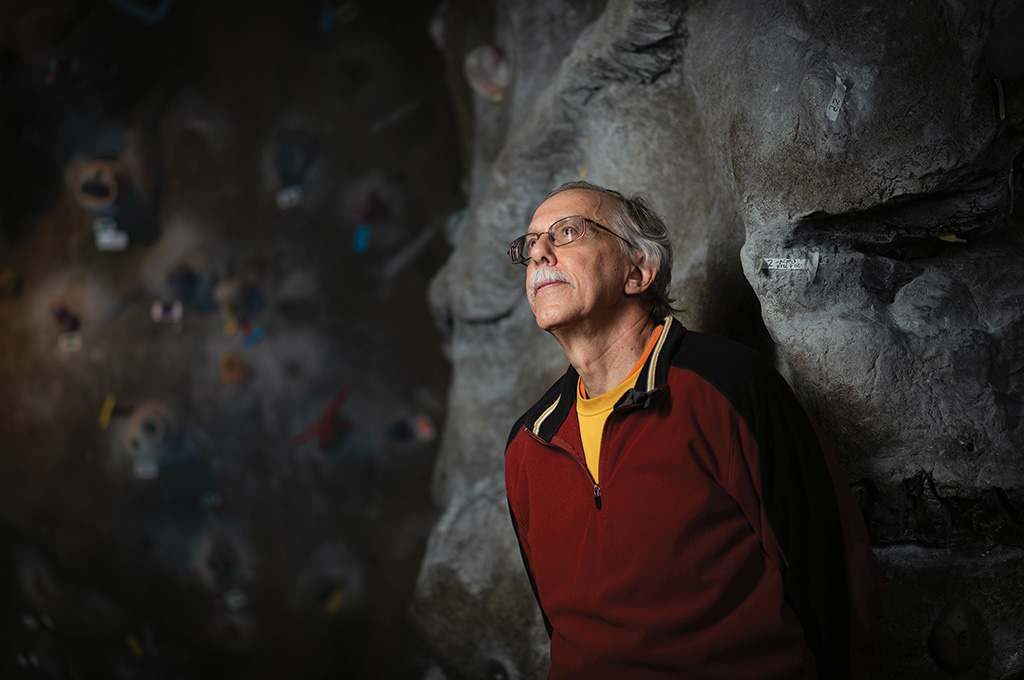

During a campus visit in October, speaking to the KU Rock Climbing Club, David described how his older brother challenged him to embark upon such a demanding sport in his 50s. Step one was rope training on an indoor climbing wall.

“He was serious about, ‘Get it done before you even think about getting on a rope with me,’” Cicotello told students. “I had to learn on the gym wall to be technically proficient, but he taught me more in the field than I ever learned in the gym.”

David was pupil to Louis’ master on the weeklong trips, which Louis planned in fine detail, down to the nightly dinner menu. He gathered wood for the massive campfires Louis built, prepped ingredients for the gourmet meals that Louis, an accomplished amateur chef, cooked. But as David grew into a more capable climber under his brother’s tutelage, the age difference between them seemed to disappear.

“I think Louis and I developed a relationship of equals through these trips to Utah because things fell away,” David says. “We were in the moment, enjoying each other’s company.” In the desolate Utah wilderness, conversation came easy. “We could run the gamut from deconstructionism to who’s gonna win the pennant, all along enjoying this wonderful canyon country we loved.”

Robbers Roost is a beautiful but severe landscape of slick red rock and prickly cactus, fragrant sagebrush and stunted cedar. Jack rabbits, wild horses and outlaws are among the tough critters who’ve called it home. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid found the deep, mazelike canyons an ideal hideout, and they cached fresh horses and food stores to sustain their Wild Bunch gang through long stretches on the lam. One of its chief charms—for bank robbers—is also one of its deadliest: remoteness. No Mans Canyon, where David and Louis were exploring, is two hours from the nearest paved road.

The Roost’s unforgiving nature was most famously illustrated by the experience of Aron Ralston, a 27-year-old canyoneer who in 2003 amputated his arm to escape a slot canyon where he’d been pinned by a falling boulder, then nearly bled to death on an 8-mile walk before having the good fortune to cross paths with a family of hikers. The site of his desperate struggle for survival, Bluejohn Canyon, is only 15 miles from where Cicotello—with a shock of realization Ralston would surely recognize—was quickly coming to terms with his own dire predicament: Robbers Roost is an excellent place to lose yourself, but one hell of a tough spot to get found.

David couldn’t see Louis, but he could hear him.

Soon after he eased over the edge, Louis had called to him: “It goes fast.”

“He was letting me know it’s a free rappel,” David says. “You’re not touching the rock face as you go down.”

Louis had one firm rule in the field, which he only rarely suspended: The most experienced climber goes first. Though he had guided David through about 125 descents, he was always looking out for his younger brother, always offering tips, urging caution.

“Then in the next moment,” recalls David, “he said, ‘Oops, the rope is short.’”

A 60-meter rope is 197 feet long; doubled to form two even strands—as it must be to accommodate the belay device that acts as a brake and allows a rappeller to control his descent—it reaches 98 feet. If it is folded unevenly, creating long and short sides that reduce the amount of double strand available to hold the belay device, the effective reach is shorter. For a rappeller, a rope’s usable length is only as long as its shortest strand.

“I can’t see my brother, but I can picture what he’s just described. The ropes have been set up uneven. Sheer panic came over me in that moment.”

Louis had run out of rope short of the ground. David doesn’t know how high above the scree Louis found himself, but what he said next leads David to believe that his brother judged the distance manageable.

“In the next sort of nanosecond, he said, ‘No biggie.’”

In the eight years since his brother’s fall, David has replayed the scene over and over in his head. Interviewers, friends and family, sheriff’s deputies who investigated the accident, all have asked how much time passed between those words and what happened next.

By David’s estimation it was three, maybe four seconds. Not much time to say, Hold on, Louis. What do you mean, No biggie?

But it was also a lifetime that ticked by, a history of being together that had become deeply grooved by decades of relating big brother to little, master to student.

“He said, ‘No biggie.’ And when my brother said, ‘No biggie,’ that meant, ‘OK, I’ve got it under control, this is gonna work out, no problem.’ He’s the experienced one; he knows what he’s doing. I’m not gonna question him.”

Panic turned to terror in the next moment as David watched the rope zip through the rappel ring and disappear.

“He didn’t cry out. I heard no crash, no hard landing,” he says. “But I knew what had happened: My brother had fallen.”

He called Louis’ name three or four times, but got no answer. Without the rope, there was no way down the cliff; he’d have to climb back the way they’d come. Forty feet of smooth red rock and an overhanging ledge stretched above him. It was an act of desperation, but he had to try, had to get to Louis. Unable to secure a toehold, he kept tumbling back onto the ledge. At some point, he heard Louis groan below. He screamed his name again but got no response. If he could just get back to the canyon rim, he might be able to find a path to the bottom, to Louis. Miles stretched between him and the help his brother needed, but what it came down to, in the end, was the first 40 feet. There was no getting past it.

Dejected, in shock, his mind ablaze with fear and grief, he sank down on the rocks and wept.

Ralston did three things climbers and canyoneers would check the box against,” Cicotello tells the KU rock climbers.

“He went alone. He didn’t leave a map. And he told nobody where he was going.”

Clad in the same hiking clothes he was wearing in 2011, with his backpack and its meager contents that day spread behind him on a table in the Ambler Student Recreation Fitness Center, he pauses to let this lesson sink in a moment.

“My brother and I left a map, people knew where we were going and we were together,” he finishes. “And shit still happened.”

Photos: Steven Puppe

A certain amount of risk is unavoidable in climbing, as his audience knows well. Every rope and harness and implement comes with a bold-print warning sewn right onto it: Climbing is dangerous.

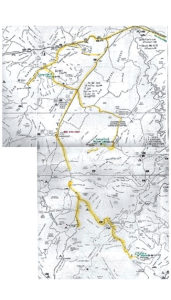

The Cicotellos did take precautions. Before leaving home, David printed out a map on which he highlighted the three campsites where they would stay, the canyons they planned to explore and the roads they’d drive to reach them. He scrawled phone numbers for the federal Bureau of Land Management and the sheriff’s departments in the three counties they’d be in, and left the map with his girlfriend, Rhonda Hoffman.

On the last night of their annual trips, David and Louis always stayed in a hotel and called home to let loved ones know they were safe. When they did not check in on Thursday night, as planned, Rhonda and Louis’ wife, Millie Yawn, would know something was wrong. Rescue crews would start looking for them the next day.

“My mantra became, Get to Friday. I couldn’t go up, I couldn’t go down. I was stuck. I had to survive until Friday.”

He inventoried his supplies: One orange, one energy bar, a small bag of cashews, half a turkey sandwich, a 16-ounce bottled water and a liter of tea with a lemon wedge he’d sliced that morning.

Over the next six days he rationed his food carefully. He ripped the backpack apart and used the foam padding to keep warm at night, when temperatures dropped into the 30s, by slipping it under his shirt and pressing it to his chest. He used spare socks as ear muffs and filled a stuff sack with sand to fashion a makeshift pillow. He blew a safety whistle daily and made a HELP sign to dangle over the ledge, though he knew odds were long that anyone would pass near enough to hear or see either. In all their visits to Robbers Roost, he and Louis encountered other people only twice.

He passed the hours tracking clouds and contrails that drifted across the crack of sky overhead. He watched birds wheel and light on the canyon walls where the shadows morphed into shapes that he began to recognize and anticipate with each passing day. At night, Orion stalked in and out of view, marking time. He gathered stray bits of tinder and lit fires that burned out quickly, more for comfort than for heat. He used his knife to carve into the sandstone walls his name—only a letter or two at a time to lengthen the diversion—and a hashmark for each day on the ledge. He sang. He prayed aloud. The 23rd Psalm particularly resonated: Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.

“Because I was in my own kind of valley,” he says. “That psalm says walk through the valley. Don’t stop. Because if you stop, you get stuck.”

Twice he doubted his prospects for rescue enough to entertain a risky scheme. In his pack he carried an etrier, a nylon climbing ladder about 8 feet long; a 25-foot static rope; and two 25-foot pieces of webbing. He twice tied these pieces together—on Wednesday and again on Thursday—before deciding not to risk his life on a jury-rigged rope. “I decided if it came to that,” if rescuers did not find him, “I’d sit down and let it come.”

By Friday he had only an inch of water left. He refused to drink the last sip until he was sure rescue was imminent; staring at an empty bottle seemed too deflating.

The sandwich had gone bad before he could finish it. So had the tea. Only the cashews remained, and he’d stopped eating them because he was so dehydrated that they turned to gum in his mouth. He’d lost 15 pounds, and frostbite gnawed at his toes and fingers. He spent the day in a hopeful mood, waiting for the sound of a helicopter, but as the shadows stretched longer and longer then deepened to darkness, no rescue came. He lay down to sleep worried that his worst fears had been realized.

Late that night, he heard the whop, whop, whop of an approaching chopper. It passed overhead, then dropped below the canyon rim and turned to shine its spotlight into the slot.

And then it flew away.

“They didn’t see me,” David says. But at least he knew they were looking.

The next morning, Saturday, they were back early, hovering outside the ledge. This time they saw Louis’ body at the base of the cliff, saw David where he stood waving his HELP sign.

He had made it. He was saved.

Throughout his six days on the ledge, David pushed grief to the back of his mind in order to focus on survival. Once he was rescued, it came flooding back.

In the hospital in Moab, doctors rehydrated him and treated his frostbite. He cleaned up and asked to see a priest. “I needed to unburden what I was feeling, which was guilt that I could not do something for my brother,” he explains. “Fear turned to grief very quickly. I had survived and my brother didn’t. That was the next emotional hurdle I had to get through.”

Back home in Tennessee, where he’d moved in 2010, he relied on his parish priest, his physician and a grief counselor to work through the trauma.

“I was devastated. I was weeping too much. I would think of Louis and just come unglued. Every time I laid my head down to sleep for about six months, I was right back in that slot. I was still stuck in the valley.”

David would startle awake at night, Hoffman says, “like he was still there on the ledge.” People wanted to know what had gone wrong. “There was a lot of Monday-morning quarterbacking from everyone, and that was hard on him.”

The counselor had him write letters to Louis to tap into his anger.

“I was pissed at Louis, and I had to deal with that. He decided what he decided to do, and I had to come to peace with that decision.”

No one knows exactly what happened on the rope. The theory is that Louis believed he was close enough to the ground to basically jump the rest of way, that he believed he could rappel off the short end, land safely and keep the rope intact. Then with David’s help he would rearrange the strands evenly to allow a safe descent for his brother.

We have no idea the distance he had to cover, but it’s clear the landing went badly, because Louis’ body was recovered some distance from where he would be expected to land on a straight vertical drop, and the autopsy indicated a broken pelvis. The force of his fall pulled the rope down behind him.

“His miscalculation ended with his death, and stranded me for six days and potentially could have caused my death,” David says. “I had to deal with that.”

The annual report “Accidents in North American Climbing,” published by the American Alpine Club to document the year’s most significant and teachable climbing accidents, classified the cause as rappel error/ropes uneven.

Louis used a piece of white tape to mark the center of the rope, David writes in the report, but “it was not always firmly attached to the rope, and he repeatedly vowed to ‘fix’ the position of the tape more securely as a future project when he was at home.” The rope had been properly coiled and marked when they set out that morning, David says, but he believes the tape was displaced from the midpoint during one of their prior descents. “As we threaded the rope for the second stage of the exit rappel, we watched for that piece of tape on the rope, and when it came near the rappel ring, we stopped threading,” David wrote. “We based everything we did from that point on what we thought was the middle of the rope.”

When he threw the ends down, Louis did not check to see that both strands touched the ground. Nor did he tie stopper knots in the ends, a safety measure to prevent someone from rappelling off the rope. (“Holding the ends of a rappel rope and coiling it until coming to the center, combined with knotting the ends with stopper knots are both recommended,” advised an editor’s note on the American Alpine Club report.) After realizing the ropes were uneven, he could have tied off and consulted with David about what to do next. He could have used a jumar, a piece of gear in his pack that allows a climber to ascend a fixed rope, to climb back up.

Instead, he judged the problem he faced to be one he could solve.

“Part of my grief and guilt is tied up in that moment, when I relied on my brother’s signal, ‘No biggie.’ And never thought for a moment to intervene. To say, well, what are you gonna do?”

A big part of David’s recovery was realizing it was his brother’s decision, not his own inaction, that led to the accident.

“I had to come to grips that my brother chose to do what he did,” he says. “It wasn’t anything I did, or that I chose not to intervene.”

In the end, the thing that tore them apart was the thing that holds them together.

“I loved my brother, and he loved me, and in those moments in the canyon you didn’t have to speak it, you knew it. And that to me is the wonderful peace that will always reside with me. I’m sure he never imagined what he was about to do would have led to what happened. Absolutely not. But it happened.”

When David first returned from Utah, in 2011, a stack of messages awaited from news outlets wanting to hear his story. He wasn’t ready. Now, sharing what he’s learned is part of his determination to avoid getting stuck in grief, to keep pushing through the valley.

“My survival story is not only in that slot canyon, but there was survival out of that canyon. I kept that canyon inside me because there was trauma that I had to get through.”

His survival story is unique, but it’s not better than anyone else’s, he says: Many of us find ourselves stranded on a ledge by divorce, bankruptcy, a bad medical diagnosis. He hopes a book he’s writing about the ordeal and his recovery from it, as well as the speaking engagements that he’s leaving the classroom after 40 years in higher education to devote more time to, will help others dealing with their own trauma. The same goes for a gift he announced during his October visit to campus. The David Cicotello and Louis Cicotello Memorial Fund will aid graduate students in English who are facing a pressing need other than tuition and fees. It’s meant to offer a boost to someone who needs a little help surviving a rough patch in grad school.

It’s one more way of honoring Louis, who guided David to KU in the first place.

Had things gone according to plan that March day in Utah, the brothers would have enjoyed lunch at the bottom of the final rappel, perhaps marveling at the path they’d traced together and the imposing, red-streaked rockface that is the exit to No Mans. Then they’d gather their gear to complete another of their canyon rituals.

“We loved to make that cross-country trip across the mesa to go back to where we had parked,” David says. Unexpected wonders often lay along the way, just waiting to be discovered. Once they found a cache of chert where earlier inhabitants had shaved arrowheads, the chips and broken tools reminders that humans called this forbidding landscape home long before they happened along, and would continue to long after the Cicotello brothers were gone.

“You wouldn’t get that,” David says, “if you were on the trail all the time.”