Statistics for Smarties and Other Fun Stuff

Whether he’s using humor to help students embrace their stats class, writing heavy books with a light touch, or recording his bubblegum pop podcast— yep, bubblegum music—Bruce Frey prefers the sunny side of the street

Side A: All the Statistics Hits!, feat. Professor Bruce Frey

Destinies can, and often do, swerve with the slightest nudge, a glance that steals a heart or a comment that calls forth action to alter everything. Professor Bruce Frey still recalls the moment when his professional fortunes first found direction.

One sentence, with as many syllables as words: “Bruce, are you smart?”

Frey, c’85, PhD’95, was a doctoral student in educational psychology at the time, working as a graduate teaching assistant with his first crucial KU mentor, Professor Nona Tollefson, “who was sort of famous at the time for just being the greatest professor there ever was.” One day he received an unexpected phone call at home from Tollefson’s colleague Professor Neil Salkind, whom he had not met.

“Bruce, are you smart?”

A simple question, but, for most of us, difficult to answer; because he answered as he did, Frey gained another mentor—and focus for what to that point had been a scattered scholarly career.

“You know, if I had given a different answer than I did, who knows? I’d be working at Family Video to this day. Or I’d be a DJ in Topeka,” Frey says. “But I said what I thought was the truthful answer, which was ‘yes.’ And so Neil hired me for a project he was working on. He was running a journal. He needed some help with that. And then he began writing books. And not necessarily scholarly books, but books for normal people.”

Because he answered in the affirmative, Frey, professor of educational psychology, started down a path that eventually brought him back to KU as a faculty colleague of Salkind’s, and—thanks in part to their shared appreciation for the offbeat and unexpected—their mentor-mentee relationship morphed in a professional collaboration that has continued beyond Salkind’s 2017 death.

One of Salkind’s enduring textbooks, Statistics For People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics, this fall was released in its seventh edition, with Frey writing revisions and updates as co-author.

“That was a very successful book, and he had Bruce in mind all along,” Leni Salkind says of her late husband’s plans for Statistics For People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics. “Bruce has the same kind of sense of humor as Neil did.”

We promise this won’t be a story about statistics, but even if it were, that wouldn’t be a bad thing—at least not as Salkind and Frey present it in their book. Nearly every page includes passages of empathy and humor, repeatedly asking students to trust their assurances that this time the dreaded topic will be different—and it is.

Readable, understandable, interesting and even fun—all of which can also be said for Frey’s own stats book, Statistics Hacks: Tips & Tools for Measuring the World and Beating the Odds.

We do acknowledge, however, that we are nowhere near qualified to present the evidence of successful statistics presentation, but there is this:

Appendix I: The Brownie Recipe

You have probably worked hard on this material, whether for a course, as a review, or just for your own edification. And, because of all your effort, you deserve a reward. Here it is.

“They were really good,” Leni Salkind recalls wistfully. “You couldn’t just have one.”

Statistics, Frey says, are “the one topic that, even for graduate students, scares most people, because it’s so different from anyone’s experience.” An acknowledged authority in research design and classroom assessment, Frey explains that good students build on what they’ve already learned, so they rarely begin a course without a base level of understanding.

“Then when they come to statistics,” he says, “it’s this whole weird, separate thing.”

When he taught introductory statistics, Frey treated the first day of each semester as a “therapy session,” during which he and the students would face their anxieties. Gaining comfort with statistics might not be easy, but it is possible, and important, and so say colleagues who don’t even teach it.

“Statistics,” contends Google Earth co-creator Brian McClendon, e’86, research professor of engineering, “is the most useful class one can take in high school or college.”

Frey anticipates students’ discomfort with the topic because he once shared it. In fact, he was never anywhere near a statistics course until he made his unanticipated return to KU as a graduate student.

He grew up in Topeka, where he gained lifelong affection for pop-culture touchstones such as comic books, Saturday morning cartoons, quirky little paperback adventure stories based on popular TV shows, and, especially, radio. His father, Don, a psychiatric clinical social worker at The Menninger Foundation, collected old-time radio recordings, and around 1980 launched his own show, “Memories of You,” a free-form Saturday program that ran for years on KTOP-AM.

Frey came to KU in 1981 as a film studies major. When it dawned on him that the nearest production studio was in Hollywood, Frey took his degree back home and went to work in a video store—“At least that was kind of related to film studies”—then followed his father’s lead and became a DJ at KTOP. As he tired of the minimum wage work, Frey took notice when a friend enrolled in KU graduate courses to study school psychology.

“I thought, oh, those are the people who give tests and they do counseling with kids, and I loved the idea of both of those things,” Frey recalls. “I always loved multiple-choice tests, I loved IQ tests, I loved ‘Jeopardy!’, all that stuff. So I said, I’ll be a school psychologist, and I applied, very naively, to the school psychology program at KU.”

One problem: His uninspired undergraduate GPA hovered below 3.0. Because he was a whiz at tests, however, Frey scored high enough on entrance exams to be admitted “on a sort of double-secret probation,” which he promptly flubbed.

“I essentially flunked out,” Frey says, explaining that school psychology, especially 7 a.m. team meetings during his practicum, was not his thing. Statistics, research design and measurement courses were, and he still relishes the first “aha!” moment, in Tollefson’s stats class, when he realized that he not only understood the topic—“because it was being taught well to me,” he notes—but he could also help others understand, too.

Given no other option Frey switched departments and, finally, flourished.

“Being a good teacher was important to me,” he says, “so I gave it a lot of thought, and I tried to be creative and innovative even as a young grad student teaching other students.”

After earning his PhD—“It was just sort of by chance and sideways that I ended up getting a doctorate in quantitative methods”—Frey took a couple of “real world jobs” involving statistical research, yet maintained his connection with KU by teaching courses, including classroom assessment and introduction to research, that senior faculty preferred to avoid.

When he finally landed a tenure-track position in the School of Education and Human Sciences, Frey, now Budig Teaching Professor, became that rarest species in academia: full-time faculty hired by their undergraduate and graduate alma mater.

“You want voices and ideas from somewhere else, not just people you’ve created,” he says. “Even if you know an internal candidate is going to be a great teacher and a good reseacher, there is still a sort of taboo against that.”

Frey, though, isn’t the only such example at KU. Turns out, he’s not even the only one in his home.

Side B: Echo Valley: The Original Bubblegum Music Podcast, feat. Professor Bubblegum

Bonnie Johnson, professor and director of KU’s vaunted urban planning program within the School of Public Affairs & Administration, came to KU in the mid-1980s from Oklahoma, intending to make her way to law school after studying political science. She originally thought she’d spread her wings at an eastern school, but fell hard for Mount Oread at first sight.

“The campus was just what I had always imagined of this ‘university on a hill,’” Johnson says. “It is that fictional university. And, they had a good political science department.”

Shortly after moving into Hashinger Hall, during Country Club Week her freshman year, Johnson, c’90, g’92, g’94, PhD’07, met a new grad named Bruce Frey when he returned to visit his Hashinger friends. They soon became a couple and have been together ever since.

“Hashinger Hall, being the creative arts residence hall, was huge for both of us,” she says. “We were able to find our people, creative people, people who weren’t always welcome in the mainstream. It was home, and to this day our best friends are from Hashinger. It was my family, and still is.”

After earning her undergraduate degree in political science—with the late Professor Burdett Loomis as a mentor—and Latin American studies, Johnson completed master’s degrees in political science and urban planning, and, while maintaining a long-distance relationship with Frey, took planning jobs in Amarillo, Texas, and Liberty, Missouri, before returning to Kansas to work for Johnson County. She caught the teaching bug by filling in at KU for faculty on sabbatical, and returned for a doctorate in political science and public administration. (Hers was the last PhD awarded by the combined department before public administration split off into its own school.)

Johnson’s vision of a university on a hill turned out to be the map of her life: education, career, family, love.

“One of my favorite memories of our first, early dating,” Johnson says, “is sitting on the steps of Hashinger Hall, looking out at the sunset, and he said, ‘Someday, all this is going to be ours.’ And here we are. We got married in Danforth Chapel. We’re full professors at KU. It is just amazing. We are a KU love story. We’re so KU.”

As with many girls of the 1970s, Johnson grew up listening to David Cassidy and The Partridge Family records. When progressive music arrived in the early ’80s, Johnson drifted away from the bubblegum pop of her childhood and never gave it another thought—until her husband announced that he was going to create a bubblegum pop radio show.

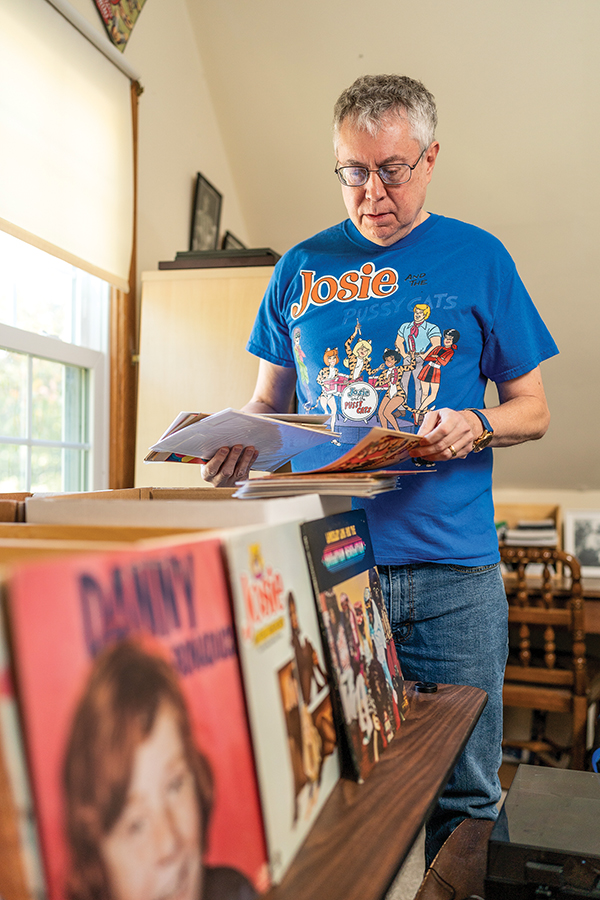

Even Frey was never a big bubblegum fan. He adored doing a fun weekly show with his father on Audio-Reader, but Frey craved a satisfying creative outlet, ideally a radio show of his own, and hit on the idea of bubblegum pop when he came to the realization that he admired classic rock ’n’ roll but didn’t much enjoy it.

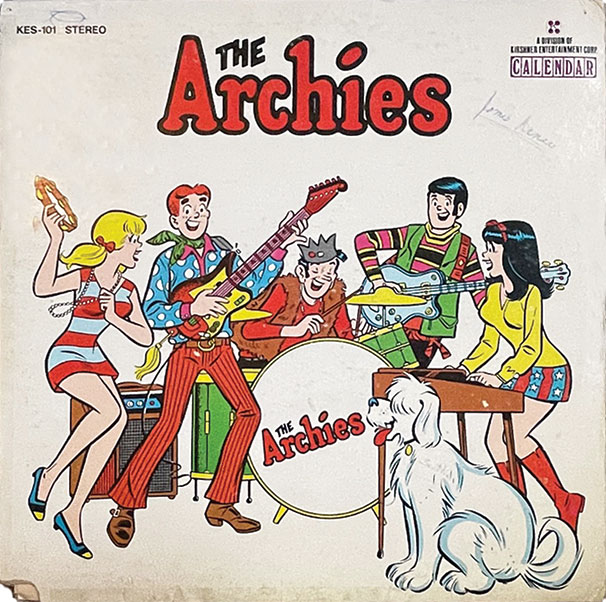

He preferred happy music, lightweight, catchy pop tunes that spoke to the “13-year-old brain in me,” and promptly identified an overlooked niche in the crowded world of radio: sweet, innocent, bubblegum, brilliantly engineered to speak to lovesick 11-year-olds.

“What if I did a show where I treated that with the same respect we give classic rock? Suppose I played a Brady Bunch song and pretended it was as good as Pink Floyd? That would be fun.”

With a format forming in his mind, Frey pitched the idea to KANU/KPR, and was told something along the lines of, cute idea, not for us. He tried again a year later; still no. That’s when Frey began assembling his own production equipment, including a good microphone and open-source editing software, and created the first episodes of a show set in the Lake Wobegon-esque fictional town of Echo Valley (a nod to the Partridge Family tune), where he would serve as mayor and citizens young and old listened only to bubblegum music.

KPR passed a third time, so Frey turned to podcasting. Eight years and more than 150 episodes later, he is now one of the world’s leading authorities on the genre, with more than 5,000 hard-to-find songs—the great majority of which were donated by fans or found online—in his iTunes library and a fully formed Echo Valley universe playing out for devoted bubblegum enthusiasts around the world.

For the first 20 episodes, Frey hosted the show as himself; it was University Distinguished Professor Neal Kingston who suggested he adopt the persona “Professor Bubblegum.” Professor Steve Lee—who had flunked Frey out of the school psychology graduate program years earlier and, as Frey notes, has been gracious enough to never mention it since—suggested Frey bundle the shows in seasons, with distinct narrative arcs. Another friend suggested the sidekick “Kid Bubblegum” and created and maintains Kid’s @bubblegum_music Twitter account.

And serving as producer? The one whose opinion he values the most, and who, miraculously, came to appreciate the historical significance and musical talent underpinning bubblegum pop.

“I thought it sounded really cool, kind of back to what brought us together,” Johnson says of her husband’s wacky idea. “When I was in high school, I was in theatre and forensics, and a friend and I did the school report on the local radio station every other week, so I have some radio, and I grew up loving comic books as well. That’s the glue that binds us.

“But who knew he would do it this long? I was like, OK, this will be a hobby for a little while, but it just keeps going.”

Beyond the music, which she’s grown to truly enjoy, Johnson sees value in “Echo Valley” for its representation of her husband’s values: kind-hearted, easygoing, avoids taking himself too seriously, a bit of a ham, looking out for others as others looked out for him.

“With the bubblegum podcast, you can listen to it just to have some silly fun,” Johnson says. “You can listen to it to learn about the roots of pop culture. You can listen to it for just the story of visiting Echo Valley, where all of your favorite cartoon characters come to life. And if you listen to the podcast over time, it tells a story of Professor Bubblegum and his mentee, Kid Bubblegum, who he takes through the ups and downs and angst of his teenage years.

“And so that’s very like an academic. You’re mentoring someone. He has his intern that he mentors on the podcast, and bubblegum music saves him.”

LINER NOTES

Professor Frey’s books are available for order online, including e-book versions for purchase or rent—yes, rent—as well as at your local library, if it’s any good. “Echo Valley: The Original Bubblegum Music Podcast” can be found online at echovalley.podbean.com, YouTube and on your preferred podcast platform, if you’re into that sort of thing. Multimedia maven Professor Bubblegum is crushing YouTube with his concise yet comprehensive history video, “The Golden Age of Bubblegum Music,” viewed 1.1 million times; Professor Frey has notched 469 total YouTube views for his charming student film from Hashinger Hall circa 1984 and a fairly hilarious cellphone video of him winning a professor prize at a KU football game, after not telling his family why they were there and suggesting that his wife be ready to shoot video of Gale Sayers during an on-field ceremony while he “went for snacks.”

Q&A interview that follows originally published in Kansas Alumni magazine, issue No. 4, 2021; questions have been condensed for clarity and also because some of them were … kinda wordy, to be honest.

Reprinted with permission.

Kansas Alumni: We’re thrilled that Professor Frey and Professor Bubblegum both took time from their busy schedules to join our correspondent over expense-account breakfast at Milton’s Café, in beautiful downtown Lawrence, for a lively Q&A sure to be of interest to their many fans.

Q: What’s your favorite song?

Frey: I’ll give you the scholarly answer here. There are two bubblegum songs that I will mention. Both were No. 1 hits, both were massive hits. Some scholars argue that one of them is not bubblegum.

Q: Bubblegum scholars?

Frey: Many would argue that it’s just a solid pop/rock ’n’ roll song. David Cassidy had a great pop voice …

Bubblegum: … purely by chance, by the way. When he was cast in the show, they didn’t think that he would actually sing. They were going to let a studio singer sing for him, but one of the great pop voices ever …

Frey: … so a lot of people would say, no no no, it’s too good to be bubblegum pop, but The Partridge Family of course was a fictional band that didn’t really exist.

Q: Wait, what? They didn’t really drive around in a groovy bus?

Frey: And they didn’t live together in a house somewhere in a fictional California town. And, except for David Cassidy and Shirley Jones, the kids didn’t actually sing on any of the recordings. I mean, Susan Dey didn’t actually sing on any of those records. But, as I say, “I Think I Love You” is, in fact, the best pop single ever made. So if it’s a bubblegum song—which I would say it is, because it’s sung by fictional characters—then that’s my favorite bubblegum song.

Bubblegum: There’s never been a better record than “I Think I Love You,” by The Partridge Family. In any genre.

Frey: There’s some Beatles stuff that’s perfectly fine, but none are better. “Let It Be” is a good song, but it’s no better than “I Think I Love You.”

Q: Uh-oh. We’re going to get letters. Will they be the fun kind of letters?

Bubblegum: At least we could have that argument without feeling bad about your fellow man.

Bet you thought we forgot. You deserve a reward. Here’s your brownie recipe, Professor Salkind’s favorite, from Statistics For People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics.

1 stick butter

4 ounces unsweetened chocolate

1⁄2 tablespoon salt

2 eggs

1 cup flour

2 cups sugar

1 tablespoon vanilla

2 tablespoons mayonnaise (Professor Salkind: I know)

6 ounches chocolate chips (or more) 1 cup whole walnuts (optional)

Preheat oven to 325; melt unsweetened chocolate and butter in a saucepan; mix flour and salt in a bowl; add sugar, vanilla, nuts, mayonnaise and eggs to melted chocolate-butter stuff and mix well; add that to flour mixture and mix well; add chocolate chips; pour into an 8” x 8” greased baking dish; bake for about 35 to 40 minutes, or until tester comes out clean.

(P.S.: “If you think [mayonnaise] sounds weird, then don’t put it in. These brownies are not delicious for nothing, though, so leave out this ingredient at your own risk.”—Neil Salkind)