Smoke screens

Research shows youth vulnerable to persuasive vaping ads

Yvonnes Chen, associate professor in the William Allen White School of Journalism and Mass Communications, is a marketing and messages expert, which is evident in the alluring title she chose for one of her popular courses: Mindfulness and Meditation in the Media.

“It sounds really interesting, and it is. I love the topic,” Chen says. “It’s about asking our youth to examine their media consumption more critically while incorporating mindfulness practices into their daily life. How can we stay more mindful despite emotions that we may be experiencing? How can we acknowledge those emotions without being dragged down the rabbit hole? How can we empty the trash in our mind so we can stay calm and be able to bring out the skills we have to face any difficult situation?”

One difficult situation in particular has lately been a focus of Chen’s research: e-cigarette marketing and advertising aimed at youths ages 11 to 17.

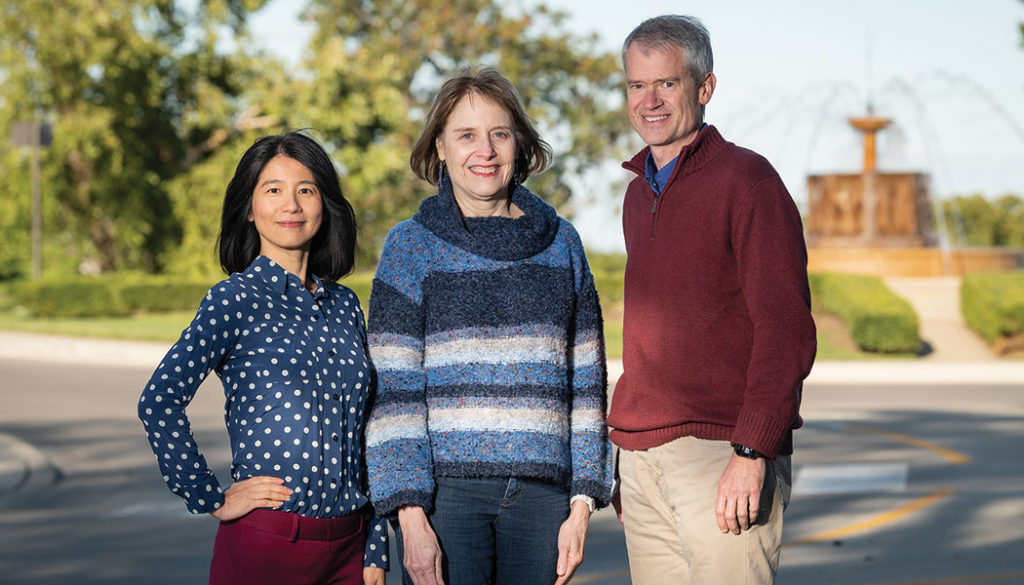

With Chris Tilden, c’86, g’92, research project manager at KU’s Center for Public Partnerships & Research, and Dee Katherine Vernberg of the Lawrence-Douglas County Health Department, Chen organized focus groups to better understand how youths perceive vaping ads and whether they view them critically.

“They are very aware,” Chen says of the study’s findings, “yet they are not critical of those ads. That would be the bullet point summary, and I think it’s a very dangerous thing.”

Funded by a Centers for Disease Control grant to the health department, the study was part of a community tobacco assessment that examined e-cigarette marketing’s inroads into youth culture. Recent reports of vaping-related deaths and illness have heightened awareness of e-cigarettes’ danger, and a leading manufacturer recently said it would halt online sales of its sweet and fruity flavored refill pods. Regardless, Chen warns, hopes for less youth demand should be tempered.

“I’m afraid that it may be a little bit too late,” she says of anything less than outright bans to prevent youths from accessing vaping products. “I don’t think the illnesses can truly scare off the adolescent who truly intends to use.”

Chen did uncover a hopeful message, however, in related research aimed at teaching young people to be more critical of commercials for sugary drinks. She says the research showed, surprisingly, that as students learned to analyze hidden messages in those ads, they also gained awareness of misleading ads in other consumer categories, such as exercise equipment commercials.

“When you teach one group of participants about viewing ads more critically,” Chen says, “they are able to transfer that skill to a different context.”

Yet vaping ads remain stubbornly effective. “Our work highlights adolescents’ trust for those ads without even questioning the content,” Chen says. “It really suggests that it is not only the persuasive power of vaping ads, but also the difficulty of doing tobacco prevention efforts.”

She describes “media literacy” as a complex process that goes far beyond the “just say no” concept of drug abuse prevention. It requires consumers to ask informed questions: Who is being targeted and who is doing the targeting? What information is missing? What are the persuasive tools being used?

Such skills need to be taught not only to adolescents but also to their parents and guardians.“We assume adults actually know a lot, but, to be honest, adults also need to be educated. Adults still need literacy training,” Chen says. “It’s not only important, it’s urgently needed.”

RELATED ARTICLES

/