Present Perfect

I am drinking a beer one fall afternoon at a tavern just off campus; a young man sitting at a table next to me, stoned from smoking a joint, is talking in that slow motion way about the war. He is 25, he says. Or 24. He doesn’t know whether you start counting your life at the end of the first year or at the beginning. In any case, he won’t have long to go before they can’t draft him. The world, he says … but he drifts off into himself for a moment. Things don’t hang together these days, he says when he comes back. He has a friend who nods in agreement; she is wearing a peasant dress, and her hair is braided in four strands so that when she brings it around her shoulder, it lies like a soft rope between her breasts. Music thumps from a jukebox. There is also Canada, she says.

From behind the counter, the waiter calls out a first name; a sandwich is ready. Outside, the class whistle blows: It is 4:20, and soon the place will be jammed with students stopping by for beer. The world, the young man says to his friend, is getting, you know … you know (and here he can’t find a word for the world and so starts to slip back into himself again) … thick, he says at last. Yes, says his friend. The autumn sunlight checkers the floor and tables. Thick, he says again, as if finding in the world both the meaning he has in mind and its opposite meaning as well. Thick.

The year was 1963; the year is 1983. In fact, this is a composite scene from cuttings and scraps of memories 20 years apart. We are all overly fond of our private déjà-vus (they’re like watching some old movie of our lives that is being run by the gods), but there is a more profound and unsettling fascination in watching the characters from one era move with apparent ease through the drama of another era. It makes you wonder what does change and what you should say about what hasn’t changed. You feel as if you are a stranger to both sets, even though you have been there each time, and even though it is nothing but one world straddling two decades. Indeed, 20 years have passed since I left the Hill, and now, as I write, they have come back again. All through the autumn, I have watched the sets and characters of the ’60s being assembled. The past seems to be speaking in the present tense.

In 1963, the campus was as innocent as the Indian Summer that burnishes it every autumn. If you were a student writer in those days, you drank your beer in the Gaslight Tavern. The Abington Book Shop was next door, and John Fowler was the owner. In the back of the store, he edited and published the literary magazine Grist Two. There was no Grist One. John had created something of a tiny rebellion in our orderly world of fraternity rows and dorm hours by publishing volume after volume—each a different edition—of a literary magazine that never seemed to go forward, and it didn’t seem to have a past. “Grind a Little Grist” was its motto. We didn’t quite know what that meant, but it had a slight edge of defiance about it, and many of us had come from high schools, my own included, where literary magazines had to be “official.” Grist Two was gentle and firmly unofficial.

There was something defiant and unofficial about the Abington Book Shop as well. To start with, you could buy your books from some place other than the Kansas Union Bookstore, where you never quite believed that all the stuffed Jayhawks and football sweatshirts betrayed a fondness for books themselves (although there always seemed to be an ample supply of This Is My Beloved and various volumes of Rod McKuen’s poetry). In the Abington, you could find genuine books: an autographed copy of Yeats’ The Vision that I regret to this day not buying; the Garnett translation of War and Peace that Simon and Schuster published during World War II and that had the genealogy of the characters as an appendix. There were wonderful old Heritage editions of the classic novels, including the generous volume of The Brothers Karamazov that took two hands to hold when you read it. In the Abington, you could buy the hardback edition of L.R. Lind’s translation of The Aeneid and then walk over to his office in Old Fraser and get it autographed.

But most important, the Abington held nothing but books. There were no cat calendars, no sunset photograph posters, no blank volumes entitled All I Know About Women. On all the walls, and on both sides of a wall that ran down the middle, and even in the back room with its mimeograph machine on which John printed Grist Two, there were books only, so that you had the feeling—maybe for the first time—that books had a life beyond Watson Library or the reading list for a course. And the beauty of the Abington was that it was virtually on campus, so that, classes finished, you could walk along the Boulevard to the Gaslight to drink, and, in between beers, you could amble over to browse the books. It gave you a slight buzz of defiance because it was so close to everything that was orderly, suburban, official.

The University once copied John Fowler’s bookstore in a wonderful little shop near the exit of the Undergraduate Reading Room in Watson Library, so you had to pass it on your way in or out. It had row upon row of new paperback editions: all of Faulkner in the Vintage series; a boxed paperback set of Durrell’s Alexandria novels; City Lights editions of the Beat Poets. There were even literary magazines: The Paris Review, Evergreen, Esquire (which you had to buy if you wanted to read the latest Borges story). The store did not last long, and I never knew why, although I suppose its demise was as predictable as the destruction of Old Fraser.

So the writers drank at the Gaslight. Two or three other kinds of students had their special taverns, too. If you were a language major, you drank your beer at the Bierstube on Tennessee Street. There were steins on the wall, and the conversation ran to travel and the translations of Faust. There always seemed to be some argument going on about the nature of German Romanticism, a phenomenon that, if you believe the German majors, influenced American literature and life more than Huckleberry Finn and sliced bread put together.

Up from the Bierstube on 14th Street, the theater students gathered at the Jayhawk Café, which was run by an open-faced man they called Buffee, who, at the end of the evening, would clear his tavern by announcing over the PA system that it was time for all froggies to hop on home—and then he would croak in a most pathetic way, as if he were the only frog left on a dark night at a lonely pond in western Kansas.

You could always tell when a play was in production because the stage hands and actors would pour into the Jayhawk just before last call to buy a string of pitchers, taking them to the high-backed red booths that were like tiny rooms. The waiters couldn’t see over the edge to tell whether you needed a refill, so the custom was to hold your glass in the air and call out some number (81, I think it was) whose meaning we didn’t know, except that it got you a refill. As a phrase, it wasn’t as rebellious as “Grind a Little Grist,” but it had something to it.

After the theater students made it into the Jayhawk, Buffee would pull the shades to signal to the liquor law people that the café was closed. If you told him there were other people coming along from play practice, he would leave the door unlocked, and the students could drift in for half an hour or so to join their friends in the booths. (I saw Moses Gunn, the wonderful actor, come in the Jayhawk late that way one night. He looked around, and Buffee pointed to a booth in the back where he knew Moses’ friends were.) After a while, Buffee would lock the door for the evening, a single action that left us night owls feeling slightly privileged, snug and convivial.

At these taverns, you had not only a sense of place, you had a place to talk, and by inference and association, you had something to talk about: poets, plays, professors. There were other taverns then, as there are now, where you listened to music or danced or got drunk in chugging contests. But those places seemed common and predictable, not unlike rush week or football games. There was a story going around then that a parent sized up the drinking habits of the students and offered to pay his son’s beer tab at one of the taverns where intellectual debate seemed to be the ambiance. Nobody was ever certain which tavern it was, so the story centered on whichever one you happened to frequent. We didn’t know it at the time, but we were part of a larger drama that was about to open.

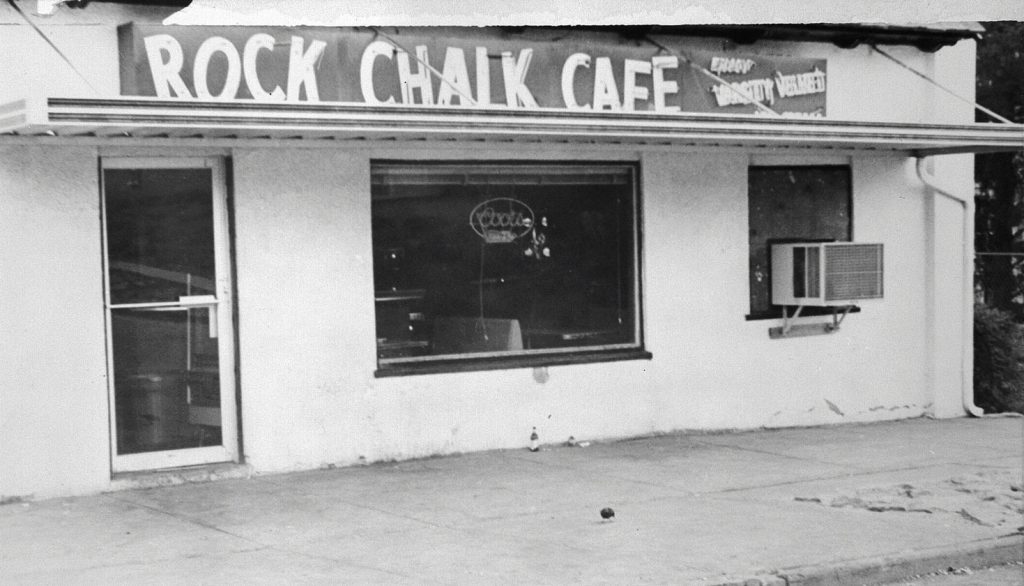

Down the boulevard from the Gaslight was the Rock Chalk Café, the setting of the scene at the beginning of this account. There was something different about the Rock Chalk. For one thing, it had a resident dog: Thor, a large white German shepherd since celebrated in Ed Dorn’s poem “The Great White Dog of the Rock Chalk.” All through the ’50s, the campus dog had been Sarge, a genial Golden Retriever who daily prowled Strong Hall basement begging food and who, on autumn Saturdays, barked at the opposing team’s mascot down at the football field.

Thor was different from Sarge, much like the students who gathered in the Rock Chalk were different from the ones who sat on the tables in Strong basement, reading the University Daily Kansan and talking about keg parties and barn dances. He was thin and something of a loner, although he was always around the Rock Chalk. In the language of the day, he was laid back, mellow. No doubt he violated some law by sprawling under the café tables among the cigarette butts, the rolling papers, and the hash pipe ashes.

There was something different about the students who drank at the Rock Chalk. Like the students of the Gaslight and the other bars, they tended to live off campus in small apartments, preferring an independent life to the dorms or the fraternity houses. And true, you thought of the Rock Chalk as the place where the philosophy majors congregated, so if you wanted to bone up on your Marx for a Western Civ exam, you could always go there and find someone who had read Das Kapital, or at least knew someone who had. But while the rest of us were hauling our courses and our studies out of the classrooms and into the taverns and cafés for talk, the students (and non-students) at the Rock Chalk were talking about things that went beyond the classroom, beyond the textbooks, and well beyond the weekend barn parties and midweek sing-alongs. It was through their portal that the ’60s flowed and flowered.

One autumn afternoon, I walked down to the Rock Chalk to have a beer and meet a friend. In the distance, I could hear the band practicing for the weekend game. I got a draft and took it out onto the front porch and sat on the steps to watch the students. From the alleyway east of the café, a couple appeared: a young woman with a long braid of hair draped in front of her so that it ran down between her breasts, and an older man, say in his mid-20s, who was wearing a plaid shirt, and whose great bushy beard and pony-tailed hair made him striking in something of a religious fashion. He had a pair of tweezers in his hand; he looked at them for a moment, then blew some ash or paper off the prongs and put them in his back pocket. There is always Canada, he said as he sat down. Yes, she said. It doesn’t do any good to get married, he said. No, she said. Not when they’ve got your number. The world, he said … and then he seemed to drift off into himself in a fashion I had never seen before. His friend sat down beside him, took his hand and put her head on his shoulder, her wonderful braid running over both of them. There’s always Canada, she says.

My own friend came along. There was a demonstration against the war that afternoon, he said, and so we left to watch it. The first thing you noticed about anti-war demonstrations was the cameras pointed at you: There were long-barreled lenses held by men who stood on top of buildings and along the fire escapes; there were 35-millimeters that were clicked into your face as you came along into the crowd. And then there were the wide-angle fish-eyes that got everyone in one photograph that you imagined was later spread out on a table where various official people looked over you (not unlike most of the students themselves, who, standing in groups well clear of the protest, laughed among themselves, stared, straightened sweaters or pulled at collars to get them to come out of the V-necks in a trim and symmetrical fashion).

I tend to think of those times as street theater, a kind of loose-knit play that might have been directed by Julian Beck and acted out over miles of stages and years of scenes. I remember realizing, that afternoon, as I saw at the heart of the crowd many of the students who gathered at the Rock Chalk, that they were of the world in a way in which I was not. Thor was there. You could not hear the marching band playing in the distance. There were hand-scrawled banners and placards badly tied to their poles and sticks. Someone gave a speech, and at the end we all sang either “We Shall Overcome” or “Give Peace a Chance,” I don’t remember which. The University, I thought as we left, is of a different world. Many of us at that time were caught in the middle.

Now, 20 years later, I stop at the University to listen to a general of some sort who has come to campus to talk about peace and war—and about various missiles he wants to set up in Europe. A number of students and faculty have shown up to protest his thinking. Once again, there are the cameras: heavy-duty Nikons of the national press; smaller Pentax models used by the campus newspaper. Across the street a team works: A man takes your picture as you come along, and a woman with a notebook comes up to ask you to spell your name. Then she writes it out and shows it to you so you can see that it will be printed correctly in the magazine for which they work.

Across the street, a television crew sets up its video equipment. The demonstrators have a banner attached to two poles, held taut so that the bright bold printing is clear and unwrinkled: “Peace.” One of the leaders has arranged the group so that there is an open shot of the sign. The video man peers into the eyepiece of his Sony; the demonstration leader looks back and, thinking the banner might be a bit too high, tells the students holding the poles to lower it a bit.

“Peace,” it says in area newspapers; “Peace,” it says on the television stations and in the Daily Kansan the next morning as the mild students of Wescoe Beach sprawl along the steps, reading the sports page and looking for taverns with good happy-hour deals. “Peace,” it might say sometime in a national news magazine.

From the Kansas Union, I walk on down the Boulevard past the aluminum trailers where the Gaslight and the Abington used to be (Annex A, Annex B, Annex C, they are marked) and the Rock Chalk Café, now called by some other name I don’t choose to remember. Students sit casually on the porch. The afternoon light seems filtered it is so soft. Some music I don’t know is coming from inside, and I go and get a beer. The place is empty. I look around as if I might find a genial ghost. The Great White Dog is not there. The papers that are scattered on the tables and chairs are full of news about Lebanon and Central America. Just like the general said, we seem to be sending missiles to Europe for Christmas. The man behind the bar tells me there must be a demonstration today because he has no business. In the distance you can hear the 4:20 whistle blow. Someone’s marijuana smoke lingers. I sit down at a table off to one side and notice for the first time a young man by a window. He is talking to himself, saying something about going to Canada to see his brother. The world seems thick to him; or something seems thick to him. It is difficult for me to hear him because he is talking only to himself. When he turns 26, he says, they can’t draft him. He is 24, or 25. I finish my beer and go back outside.

Jogging down the street are two young women. They are wearing shorts and short-sleeved shirts, and the late afternoon sunlight enhances their wonderful tans and their beauty. Their outfits match in a way; both wear those tiny radio headsets that you see everywhere. They jog on in silence, though in their heads there is music. I wonder whether they know, or whether the young man talking to himself by the window in the Rock Chalk Café knows, that they might well be characters in a people’s play. If it is anything like the previous one, the drama will be sprawling and profound, taking in even those of us who have remained mostly an audience to it all.

Robert Day, c’64, g’66, is a frequent contributor to Kansas Alumni and the author of the new book Protests Past: Short Stories and Essays on College and University Life in America, from which this essay is reprinted.