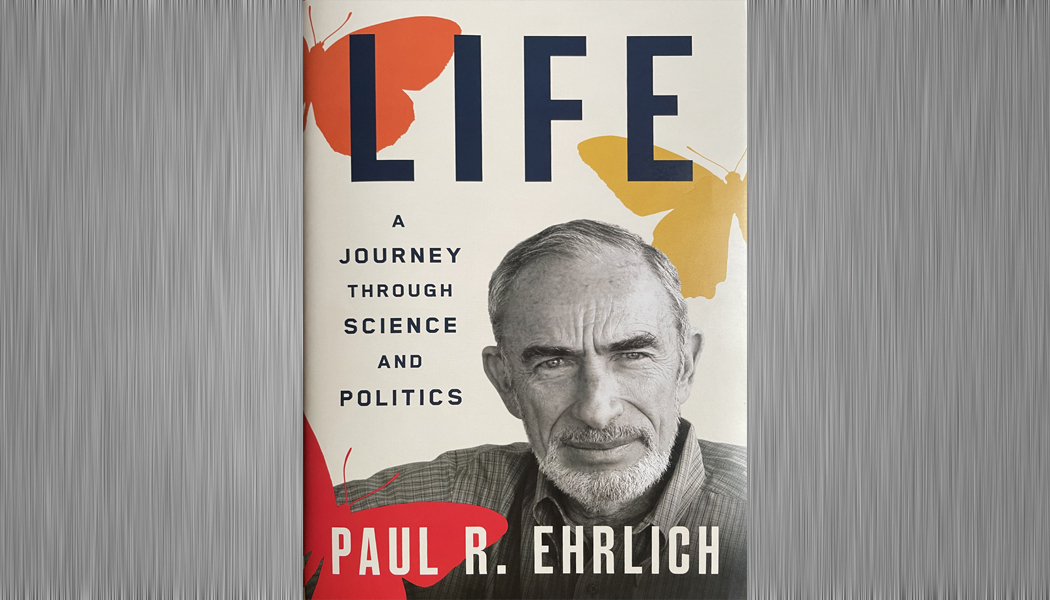

Paul Ehrlich: Citizen, scientist

KU alumnus and one of biology’s titans looks back on a life well lived in new book.

After the 1968 publication of The Population Bomb, the blockbuster book that warned humanity must control its population growth or face oblivion, Stanford biology professor and author Paul Ehrlich was labeled by critics a child-hating, anti-human “population nut” and received death threats. The book, written in three weeks and inspired by a speech Ehrlich gave in response to Rachel Carson’s seminal work of environmental advocacy, Silent Spring, struck a more harmonious chord with readers, going on to sell more than 2 million copies: “not bad,” Ehrlich, g’55, PhD’57, writes in his new autobiography, “for a book by

two academics!”

As he does throughout Life: A Journey Through Science and Politics, Ehrlich takes the opportunity, in discussing a key moment in a life bursting with highlights, to set the record straight. His wife, Anne Howland Ehrlich, ’56, was his co-author (the publisher insisted on crediting only Paul), and their preferred title was the more measured Population, Resources, and Environment. Far from “anti-human,” they were if anything too optimistic in their projections of humankind’s ability to rein in our out-of-control impact on the Earth. And while many of their dire predictions of global famine did not come to pass, as critics have pointed out, most of their broader arguments about the unsustainable relationship between people and our planet have largely held up.

The Population Bomb and Ehrlich’s 10-year run as a frequent guest of Johnny Carson on “The Tonight Show,” which began in 1969, may have marked the peak of his life as a pop culture phenomenon, but Ehrlich’s impact as a scientist and nature advocate is far broader, as Life explores with great detail and good humor. During a Depression-era childhood in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, young Paul began a lifelong fascination with butterflies in particular and the natural world in general. This “early interest in butterflies as beautiful and diverse organisms,” he writes, “evolved into a fascination with much broader scientific issues.”

He arrived at KU in 1953 to study with Charles Michener; the renowned bee expert was “the best scientist working with insects,” Ehrlich had been told, “correctly, it turned out.” Graduate school on the Hill—which earns an entire chapter—introduced him to the rough-and-tumble politics of academic science and life. Ehrlich writes that he and a KU friend “organized mixed groups of African American and white students to patronize Lawrence restaurants,” which, along with movie theatres, were then segregated. The protesters received death threats (a taste of things to come, for Ehrlich) but no actual harm, and he credits their campaign, alongside the well-documented efforts of Chancellor Franklin Murphy, c’36, and Wilt Chamberlain, ’59, for persuading Lawrence businesses to desegregate. At KU he also met Anne, in the Kansas Union, and after a two-week courtship convinced the woman who would become his partner in life and scholarship that they should marry.

By 1959, Ehrlich was ensconced as a faculty member in Stanford University’s biology department, in a job he later learned had been offered first to E.O. Wilson, another prominent bioscientist with whom Ehrlich would share the discipline’s most prestigious award, the Crafoord Prize, in 1990. “I was interested in using insects as a tool for looking at evolution and ecology,” Ehrlich announced early on, “and I wanted to use field studies (in nature, not the lab) to answer questions I considered important.”

The extent to which he did so in the course of a long and impressively varied career as a “conservation biologist with broad interests” is thoroughly detailed in the scientific breakthroughs (most prominently, the co-founding of the field of coevolution), heavily cited papers, planetwide field studies, and legions of professional partners and friends remembered fondly in Life. That he did it while enjoying fine wine, good humor and good company seems to be a sustaining joy as he looks back, from his 90s, on the long fight to convince his fellow man that survival depends on adopting a more sustainable mode of living.

“The biggest question is: How to get from where we are to where we want to go?” he writes near the end of the book. Recognizing our situation, identifying solutions, and following through with the big changes needed will be difficult, he admits. “But it has long seemed to me that the very least we should do is try.”

Steven Hill is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

/