A Star Is Born

In that particular way of busy, successful, well-rounded achievers, Jenny Raff was already exhausted when her life changed early on the cold morning of Feb. 8.

Raff, an anthropological geneticist and associate professor of anthropology, typically teaches two undergraduate courses, supervises graduate students while directing her department’s graduate studies sequence, and is principal investigator on about $1 million in grant-funded research (conducted in a high-tech, super-clean lab in the basement of Fraser Hall) into the earliest genetic histories of the peopling of the Americas.

She also is the mother of a toddler, Oliver, and despite the loving support of an attentive husband—Colin McRoberts, assistant teaching professor of business law in the KU School of Business—as well as her mother and sister, both of whom moved in during pandemic disruptions, Jenny Raff rarely enjoys a moment that’s all her own.

And so, while making coffee early that morning, she savored a rare interlude of social media brain drain. Tune in and tune out, wait for the caffeine to kick in before facing the day.

“I was, you know, reading Twitter, as one does, in the few minutes before Oliver wakes up,” Raff recalls, “and somebody tweeted at me, ‘Oh my god, look at this!’ And I was like …”

Gasp!

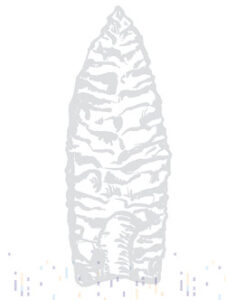

What Raff found waiting for her that morning was a New York Times review of her new book, Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas, a sweeping summary of her field meant for a general audience while still worthy of her colleagues’ interest and her own academic credentials. Years of heavy academic and creative labor researching and writing the book had contributed to her exhaustion that morning, but in an instant, Raff sensed she would now face an entirely new level of challenges.

Rave reviews in The New York Times mean the world will most definitely come knocking.

“In her new book,” wrote Dartmouth University anthropologist Jeremy DeSilva, “Raff beautifully integrates new data from different sciences (archaeology, genetics, linguistics) and different ways of knowing, including Indigenous oral traditions, in a masterly retelling of the story of how, and when, people reached the Americas.”

DeSilva praised Raff for explaining the genetic and archaeological evidence that questions previous assumptions about when and how the first people arrived in the Americas, but he also noted the humanity found throughout Origin: “lovely vignettes of life thousands of years ago,” including reflections on a family’s pain when they “placed the limp body of their 2-year-old boy into the earth” nearly 13,000 years ago.

“Through a combination of rigorous science and a universal humanity,” DeSilva wrote, “Raff gives ancient people a voice.”

The review shot Origin up through The New York Times and Amazon nonfiction bestseller lists and made Raff an instant star among KU faculty. (She was chosen as the face of the KU Center for Genomics’ successful proposal in the University’s Research Rising competition; see Rock Chalk Review, p. 10.) Raff conducted interviews on NPR, the Harvard Book Store described her as a “celebrated anthropologist,” ScienceNews.org praised the book’s “clear, nontechnical language,” and the Times even revisited Origin in a book review podcast and as the lead item in its Feb. 17 “Inside the Best-Seller List” compendium.

“It’s kind of a tour de force,” says department chair Dennis O’Rourke, c’73, g’76, g’77, PhD’80, Foundation Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, “because she covers a lot of ground both in anthropological genetics, which is her own field of specialty, but also for the amount of work she did to consult with archaeologists and Indigenous communities, community leaders and ethicists. To be able to effectively integrate those areas into a more coherent whole is a very impressive piece of work.”

Ever eager to praise others, Raff says her publisher, Twelve Books—which publishes one book a month and mounts publicity campaigns designed to engage national discussion—had faith in her book, which she describes as “a love letter” to her discipline, from the start.

“I think when I signed on with them, I had a suspicion that this had the potential to become, you know, a ‘big book,’” Raff says, “but I don’t think I was prepared for the scope.”

Jenny Raff spent much of her childhood in Springfield, Missouri, where, as she lovingly details in Origin, her father—a now-retired quality assurance engineer and “classic tinkerer” fond of amateur science projects—introduced Jenny to ethical, respectful, attentive attitudes and techniques while exploring Ozark caves.

Her mother, then a nurse, returned to school at what was then Southwest Missouri State University for undergraduate and graduate degrees in neuroscience, then completed her PhD at Indiana University after the family left Springfield. As with her father, Jenny also tagged along with her mother—whom she describes in Origin as “my first and greatest science teacher”—

becoming encoded with a passion for scientific inquiry and insights into academic life.

“I was really, really privileged, but I didn’t see it at the time, because, of course, I was a kid and I was complaining about having to spend all day on campus in the summer,” Raff says. “But I spent a lot of hours in labs, and that really instilled in me a profound love for biological sciences.”

As an undergraduate at Indiana University, where she went on to earn dual-major doctorates in the departments of biology and anthropology, Raff’s first advanced archaeology professor fit central casting’s image of the macho, dashing scientific explorer whose “tanned and deeply lined face, which attested to decades of excavating outside in the hot sun, served as much a badge of authority as the air of absolute certainty in his words.”

Raff recalls hastily writing in her notebook, preserving the great man’s proclamations, “There are no sites in the Americas that predate the Clovis culture.” An undergraduate in no position to argue or even imagine otherwise, Raff became “completely convinced.”

Clovis, referencing a culture identified with the early 20th-century discovery of remarkable stone points in the New Mexico desert, dated the first people of the Americas to about 13,000 years ago. The theory, as Raff learned, became entrenched—and remains so, in some obstinate corners—despite modern discoveries pushing the timeline back at least another 7,000 years. It wasn’t until she began working with her graduate adviser that Raff first learned that most geneticists had already grown weary of the “Clovis First” model.

A detailed accounting of how Clovis First came to dominate the field, and its subsequent displacement, occupies extended passages within Origin. The methodical, thrilling scientific journey—which is unfolding still, with KU researchers at the forefront of the hunt for answers—tickles the modern human imagination, as evidenced by our sudden passion for DNA tests to learn about personal ancestors and hit television documentaries that dramatize the scientific chase.

“We tend to have a curiosity about where we came from as a people,” O’Rourke says. “It seems to be something that has always fascinated people.”

As Raff makes abundantly clear, with writing and presentation accessible to anyone with even a passing interest in human origins, the search continues for answers to when and how the earliest peoples of the Americas arrived and flourished. And yet, as Origin attests, the fieldwork and laboratory explorations are not the whole story.

Not even close.

Raff opens Origin by recounting the 1996 discovery of “an extraordinary window into the past”: a cave on the northern tip of Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. Beyond its scientific wonders, the event is emblematic, in Raff’s telling, of the right way to conduct such investigations. Scientists on the site immediately contacted local Haida and Tlingit tribal councils and asked their permission, and blessings, to proceed. (Haida councils chose to defer to the Tlingit, as the Tlingit communities of Klawock and Craig were closest to the site.) Because tribal elders were consulted early and often, community members eventually agreed, with strict conditions: The work must cease if it is determined that the cave was a sacred burial site, the tribes must be kept abreast of any scientific discoveries before they are made public, and, of course, their ancestors’ remains must be reburied as early as possible.

In an interview with Raff, local archaeologist Terry Fifield recalled that “council members wondered who this person might be, whether he was related to them, how he might have lived. It was that curiosity about the man that inspired the partnership at the beginning.”

Over five seasons of fieldwork, scientists determined that seven human bones and two teeth, all scattered by carnivores, belonged to a man in his early 20s who lived on a seafood diet and had apparently engaged in long-distance trade for the high-quality stone used to make his weapons and tools for Arctic hunting.

He roamed that region 10,000 years ago, and his remains, Raff writes, were at the time the oldest in Alaska.

Remarkable to the scientists, but not the Tlingit, whose history and tradition teach “that their ancestors were a seafaring people who have lived in this region since the dawn of history.” Given a tribal name that translates to “Man Ahead of Us,” the ancestor’s remains were reburied in 2008; thanks to the respectful interactions with his modern descendants, scientists were also allowed to sample a small portion of his bones for future DNA analysis—which has now revealed yet more detailed stories about his origins and influence.

“The peopling of the Americas,” Raff writes, “is not simply an esoteric bit of science and history, important to only scholars and intellectuals. It is a story of resilience, compassion, intrepidness, adventure, and loss.”

Such respectful interactions had never before been the norm. Raff shares difficult histories of how colonists used “scientific” and even Biblical justifications to plunder the continent, and how even as the modern scientific method emerged, respect and heartfelt caring were too often not part of scientists’ agendas. Notably, Raff even explains in fine detail the subtle differences and meanings among various English-language terms for peoples of the Americas: Native peoples, Native Americans, Indigenous peoples, American Indians, Indians, Amerindigenous, Natives, First Nations, First Americans, Paleoamericans.

“Jenny is a very enthusiastic person,” O’Rourke says. “She loves the field. She loves the question. She likes the challenges, especially confronting the unpleasant parts of the history of the discipline. We all could wish they didn’t occur, but they did, and she’s quite enthusiastic about finding ways to make sure those kinds of excesses never happen again, and being far more inclusive and respectful in the work that goes on in the future.”

University Distinguished Professor Rolfe Mandel, g’80, PhD’91, one of Raff’s colleagues in the search for the earliest people of the Americas, notes the respectful attitudes Raff illuminates in her book are also evident in her very presence within KU’s department of anthropology.

“Some people have a hard time parking their egos at the door. She does not,” Mandel says. “She’s very cordial, very humble, extremely humble for what she’s accomplished. I’ve seen people, especially in academia, who are just the opposite of that.

“She’s a role model. I can’t say enough good things about her. We’re really lucky to have her.”

Raff hopes Origin can help educate the public and students in her field about the right way to approach and conduct genetic and archaeological research. She’s nervous, though, about being seen as preachy toward her scientific colleagues, the majority of whom, she says, need no reminders from her about how to conduct their inquiries.

Raff is also nervous about being tagged with the exact descriptor Mandel used: She does not see herself as a role model, especially for young women scientists striving for continued gains in access and inclusion.

“That implies to me that I’ve got things figured out, and I really don’t,” Raff says. “I don’t think that my life should be a good model for younger women who want to get into the sciences, just because I always do everything the hard way. And that’s not the way. They don’t need to do that.”

While writing Origin, Raff had to carve out long weekends in libraries and even writing retreats in quiet hotel rooms.

“But, you know, there are some sacrifices, right? I’ve been an athlete my entire life, and I had to completely give that up. So I don’t have a good work-life balance at all. I’m struggling to regain that. I kind of thought I would get back to it after the book was out, but the book has taken off in a way that I didn’t expect.”

Raff grew up as a devotee of martial arts and even had a couple of “very abbreviated, not very glamorous, not very distinguished” amateur fights.

Her sister, Julie Kedzie—a graduate of of the University of Iowa’s vaunted creative writing program whom Raff describes as one of her most important editors during the writing of Origin—was the star in the family. Raff says Kedzie was an “extraordinarily good” mixed martial arts pioneer, fighting out of a top-flight club in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which allowed Raff the opportunity to “train with some of the best MMA fighters in the world, because they all cycled through there.”

Raff says she stopped training during her pregnancy, a pause that extended through the pandemic and the writing of Origin. She is eager to return, to again embrace sweat and physical exhaustion, in part to rekindle a lesson she derived from rigorous martial arts training: She can “take a punch and still keep going.”

“But that applies more generally to the rest of my life. Writing this book was such a monumental task, and I’d never written or done anything on this scale before. It was so frustrating, but I think it was my martial arts training that got me through the hard parts, knowing that I just have to show up again and again, keep showing up every day, keep working hard and be patient with myself and trust the process.

“And, at the end, it will be over one way or the other, when the bell rings or when the book is sent to the publishers.”

Or until a tweet arrives, announcing that the work is far from finished.

Not even close.