Offbeat Tradition

When Roy Guenther and Curtis Marsh, Jayhawk musicians of different generations, sat down to coffee near Guenther’s home in Vienna, Virginia, less than a year ago, the two never expected their conversation would yield surprising revelations.

Guenther, d’66, f ’68, who has rarely returned to Lawrence, was simply eager to hear news from the Hill, delivered by Marsh, j’92, KU Endowment’s associate development director for the School of Music.

But as the two former Marching Jayhawks compared notes and memories, Guenther, who played trombone in the band, recalled the time in 1966 when a professor asked him to create a special arrangement of KU’s beloved fight song, “I’m a Jayhawk,” for the University’s 100th birthday. As he told his tale, Marsh realized that Guenther was untangling the origins of one of KU’s most mystifying traditions: the famously complicated hand clap that accompanies “I’m a Jayhawk.” Even better, Guenther was equally amazed to learn that his version of the song—which he presumed was long forgotten—endures to this day, accompanied by the maddening, manic hand-clapping tradition that even the most astute Jayhawks struggle to master.

Marsh’s curiosity about the hand-clapping habit stems from his nearly 15 years as director of KU Info, the “front desk of the University,” as he affectionately calls it. Before joining Endowment’s staff, he led a troupe of students entrusted with answering all questions about KU, especially queries about quirky customs.

“We were constantly getting questions about KU traditions,” he says. “People wanted to know the origin stories of these traditions. Some of them we were able to come up with, and others we weren’t.”

One traditions tale that remained elusive was the history of the hand clap that punctuates the fight song, composed by KU graduate George “Dumpy” Bowles. For decades the clap has been taught at Traditions Night, the annual event (until this strange semester) that marks the conclusion of Hawk Week and imparts the intricacies of KU’s culture, cheers and chants to freshmen. The University also has produced a few videos, which Marsh has appeared in, and other tutorials to help confused Jayhawks master the hand clap.

“I think one of our challenges from years of trying to teach this is that many times the person who’s teaching it is a musician,” he says. “We start talking about these musical terms and this jargon that makes perfect sense to anyone who has had to play an instrument or is a musician, but it goes over the heads of non-musicians. If we say, ‘All you have to do is clap on the offbeat,’ immediately someone says, ‘Well, hold on. What do you mean clap on the offbeat?’”

Despite KU’s best efforts, Marsh says, the clapping sequence has become diluted over the years, as different styles have emerged. “There is a right and a wrong way of doing it,” he says emphatically.

“There are some students who are doing it differently than the way we’re teaching it. You’re supposed to be clapping when the notes are not being played, and that’s crazy hard.”

After KU, Guenther settled in the Washington, D.C., area, as he began his long career at George Washington University, where he became professor and chair of music before retiring in 2014 as executive associate dean. Until he met Marsh for coffee in November 2019, he hadn’t thought much about 1966, when Ken Bloomquist, then director of KU bands, asked him to create new arrangements of the fight song for a halftime performance celebrating KU’s centennial.

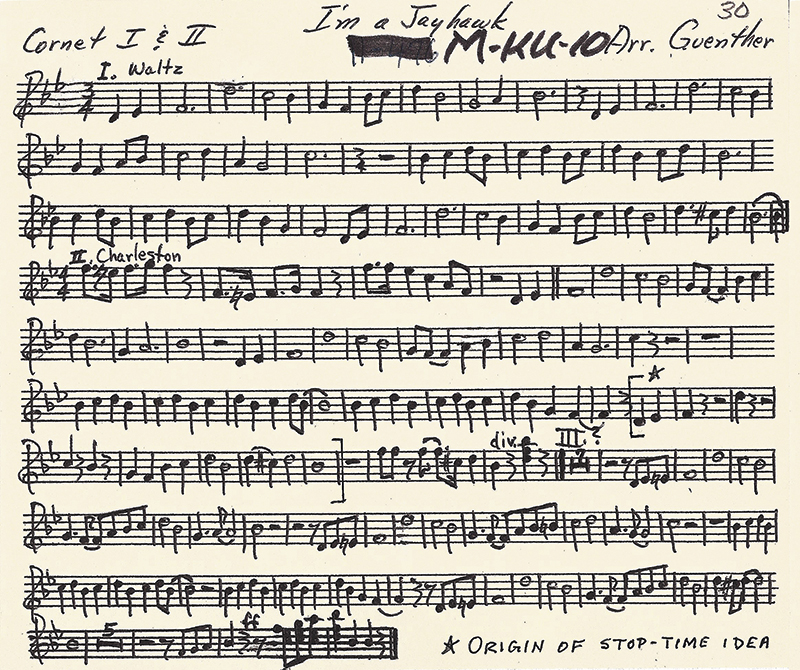

“I wrote a waltz, a Charleston and sort of a big-band sounding thing, all using the fight song melody,” Guenther recalls. “You could hear the fight song all the way through without any trouble; it just sounded a little bit different because of the different musical styles.”

As Guenther casually explained to Marsh, his Charleston arrangement included a section he called stop-time, a musical technique in which a band plays a pattern of short chords separated by silence. To create the effect, he replaced the song’s long notes with short, crisp, staccato notes in the last few bars.

“When he explained it, I said, ‘Roy, I think what you’re describing is exactly how the band plays the fight song today,’” Marsh says. “I think I’ve accidentally discovered the person who created the arrangement of the fight song.”

Marsh returned to Lawrence determined to trace the rest of the story. Sure enough, he learned that Bloomquist so loved Guenther’s stop-time arrangement of the fight song that he instructed the band to include the staccato notes throughout the entire second verse, not just the last section, as Guenther had originally written it. In the summer of 1970, Jim Barnes, f ’74, g’75, a student of Guenther’s who later became professor and associate director of bands at KU, officially rearranged the fight song at Bloomquist’s request, incorporating Guenther’s stop- time feature in the song’s second verse.

Despite laying claim to the arrangement of one of KU’s most recognizable tunes, Guenther never knew—until his conversation with Marsh—that the arrangement he created nearly 55 years ago inspired the versions performed today, nor did he know that students had created a clapping sequence to accompany the tune.

“I’ve been back on campus, but I haven’t been to a basketball or football game since I graduated,” Guenther says, explaining that although he occasionally hears the band during televised games, he has never heard the clapping. “I didn’t know anything about it.”

After hearing from former band directors that the clap might have started with the KU Color Guard, Marsh reached out to alumni band members on social media for confirmation.

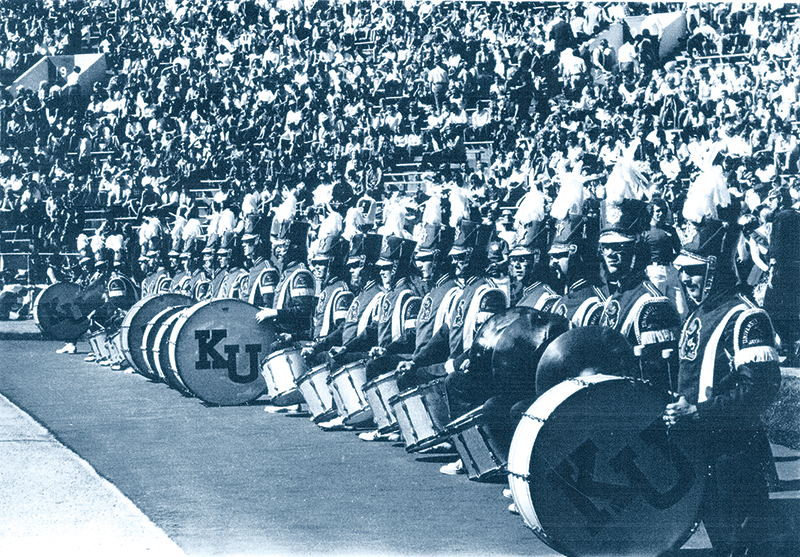

Gary McCarty, d’76, who played the snare drum with the Marching Jayhawks, was one of many to reply to Marsh’s post. He explained that in the early- to mid- 1970s the drummers grew frustrated with other band members rushing the stop-time rests in the second verse of the fight song. So, they started clicking their drumsticks together during those breaks to slow down the tempo and fill the silence with sound.

“I think it was around 1973 or thereabouts, the snare drums, we started clicking our sticks together up high, you know, right in front of our faces and then reaching out and clicking sticks with the guys on either side of us,” says McCarty, who lives in Bella Vista, Arkansas, after retiring from a 30-year career as a band director at schools throughout Kansas and Missouri. “That just became something we did, mostly to keep time going, but it added a little bit of visual stuff, too.”

A few years after introducing those stick clicks, McCarty recalls noticing that as the drumline was coming off the football field following a halftime performance of “I’m a Jayhawk,” students in the stands were clapping along to the drummers’ stick clicks. “I thought it was kind of neat they picked up on that,” he says with a chuckle. “I guess it has grown into a thing.”

When Sharon Ramsey Toulouse was hired in 2012 as assistant director of bands in the School of Music, she met one of the most essential criteria for the job: a keen understanding of KU culture as a former drum major and member of the Marching Jayhawks and men’s basketball band.

“A lot of the traditions we have now we had when I was here,” says Toulouse, f ’97, g’05, who also directs the men’s basketball band. “The claps, pregame, the run in, the high step—all of that is really big-time tradition.”

Though few KU traditions have changed over the years, Toulouse has seen the addition of new ones, including the crowd’s participation in the game-day favorite “Fighting Jayhawk.” In recent years, KU students, alumni and fans can be heard echoing an enthusiastic, “Oo-oh, oo-oh” during a portion of the song led by the brass section. The distinctive addition began with students.

“That wasn’t there in my undergrad,” Toulouse says. “It was a trombone part. When I came back years later, I think it was for Homecoming, it was like, whoa. You could hear the whole crowd doing it.”

It’s a great example, she says, of how student-led tradition develops organically. “You just can’t force it—and I’ve tried. There have been some things with the basketball band that I’ve tried to do and you just can’t do it unless they come up with it themselves.”

The same can be said of the decades-old clapping tradition that accompanies the fight song. “It is such a strong example of how students own these traditions,” Marsh says. “I don’t just mean that they start it. We can point to students deciding to walk through the Campanile before they walked down the Hill, students deciding they weren’t going to wear freshman beanies anymore. The fun story about students hanging the ‘Beware the Phog’ banner. This is another example of how these very important traditions become the fabric of Jayhawk nation. They all start from this fun activity that students chose to do.”

As for the band’s role in supporting many of these traditions, Toulouse says they take pride and ownership in their involvement. To this day, the Marching Jayhawks still click their drumsticks together and expect the crowd to clap along at the right time. “If somebody does the clap wrong, they get very offended,” she jokes.

Since learning of the legendary clap, Guenther has attempted it on his own— with limited success. “The thing that I find interesting about it is that it’s hard—and I’m a musician,” he says with a laugh. “The speed the fight song is played, to fill in those rests, the silence, with claps in rhythm is very difficult. You don’t just sort of say, ‘Oh, yes, I’m going to do this’ and start doing it. No, no, no, you’ve got to practice it.”

Make no mistake: Mastering the hand clap is “a badge of honor,” Marsh says, worn proudly by students, alumni and fans who perform it correctly. After years of struggling to find just the right way to teach it, he hopes that by sharing the history, he and others can inspire more Jayhawks to learn the clap the correct way—and at long last perform it as one.