Natural woman

The world according to Dolly subject of Smarsh’s newest nonfiction

In her 2018 book, Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, Sarah Smarsh took a sledgehammer to the myth that America is a classless society, using her own upbringing in south central Kansas to look at the barriers the globalized economy raises to working-class families like hers. A finalist for the National Book Award, Heartland spun whip-smart critiques of the systemic roots of income inequality while also paying tribute to the strong, hard-working people in Smarsh’s life, especially her mother and grandmother. More than culture criticism, the memoir gave working-class women a voice.

While finishing that project, Smarsh, c’03, j’03, was taking on another: A journalism fellowship sponsored by FreshGrass—a grassroots music foundation that publishes the esteemed music journal No Depression—commissioned her to write a four-part series on Dolly Parton.

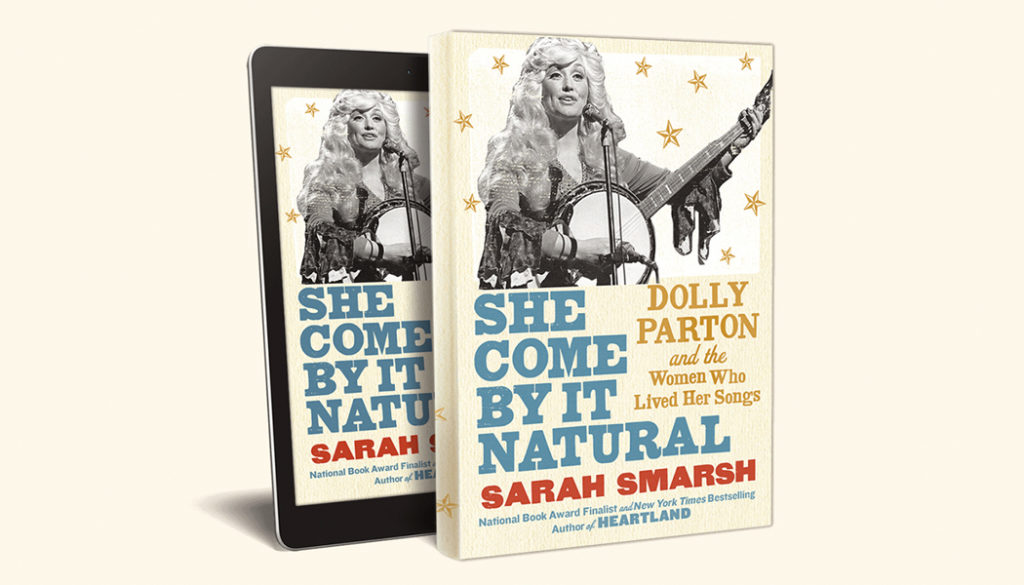

She Come By It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs, a slightly edited version of the series No Depression published in 2017, brings the same savory mix of biography and analysis to bear on a woman who, Smarsh convincingly argues, is the most successful female artist in country music history.

The big surprise, for both country fans and for those who see the singer from Tennessee’s Smoky Mountains as a caricature, is by how many measures that “most successful” title applies.

Smarsh examines Parton’s legacy as music and film star, savvy business magnate and genre-busting global pop-culture icon, arguing that she’s a feminist role model for women unlikely (as is Parton herself) to use the term. Given the importance life experience holds in all of Smarsh’s writing, it’s no surprise that the “women who lived her songs” are to a great degree the same women who formed the bedrock of Heartland—her mother, grandmother and Smarsh herself.

“In my family country music was foremost a language among women. It’s how we talked to each other in a place where feelings weren’t discussed.”

“I was a reader, when I could get ahold of something to read,” she writes in the introduction, “and literature showed me places I’d never seen. Another art form, though, showed me my own place: country music.” Education opened up a broader world, in other words, but country music affirmed that the world she grew up in was integral to her identity, not something to escape from.

Among the more powerful anecdotes Smarsh shares is an admission that country songs were often as close as her family got to emotional communion. “In my family country music was foremost a language among women,” she writes. “It’s how we talked to each other in a place where feelings weren’t discussed.” For her and her mother, this happened most often in the car, not face to face but side by side, rolling down a country road with the radio on. “Listen to the lyrics,” her mother would say.

Though she didn’t get an audience with Parton, Smarsh has plenty of extant interviews to plumb—including some cringeworthy TV appearances where Oprah Winfrey, Phil Donahue and Barbara Walters all asked her to stand so they could scrutinize her famously curvy figure. She also draws to good effect on Parton’s autobiography, Dolly: My Life and Other Unfinished Business, and her movie roles, especially “9 to 5,” in which she and co-stars Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin turn the tables on their male chauvinist boss, a precursor to #MeToo power shifts. Smarsh also explores Parton’s ongoing moment in today’s pop culture maelstrom, where the 74-year-old has been name-checked by Nicki Minaj, celebrated as a kind of kitschy female goddess and hailed as a hero by LBGTQ youth, for whom she’s long expressed support.

The power of She Come By It Natural lies not in new revelations about Parton’s personal or public life, but in how Smarsh draws out the impact she has left on the culture. Exploring Dolly’s role as an entrepreneur who made all the right moves, from leaving a professional partnership with the domineering singer Porter Waggoner to controlling her own publishing rights and opening a series of successful ventures that have allowed her to inject millions into the Appalachian region where she grew up, Smarsh finds a woman who leads by example. Calling Parton “a skillful ‘uneducated’ ambassador for feminism,” she notes that “most women I grew up among in rural Kansas do not know who Gloria Steinem is, but they know the lines in Parton’s late twentieth-century movies by heart and recognize themselves in her image.” Women should be given the freedom “to do feminism however they please,” she writes—Parton’s way or Steinem’s way—because “both charted the course for us to nominate a woman for president in 2016.”

By tracing how Parton’s music grew out of her childhood poverty, Smarsh finds a connection not only to her own life, but also to the lives of working-class women. For those folks, she argues, Dolly’s songs are not just songs, they’re a way of life. And those songs—and presumably the women they speak to—are far more multidimensional than some give them credit for.

RELATED ARTICLES

/