Moments of Inspiration

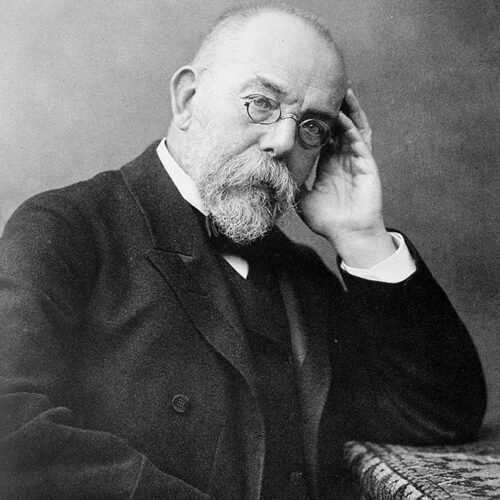

Decades before winning the 1905 Nobel Prize for identifying tuberculosis as a bacteria-borne disease, among other insights that saved millions of lives and became bedrock of modern medicine, the newly minted physician Robert Koch found himself thrust into service as a Prussian army surgeon during the Franco-Prussian War. The conflict lasted but a year, from summer 1870 to late spring 1871, yet the wounds that men inflicted upon men provided, at terrible cost, urgent opportunity to advance the science of healing.

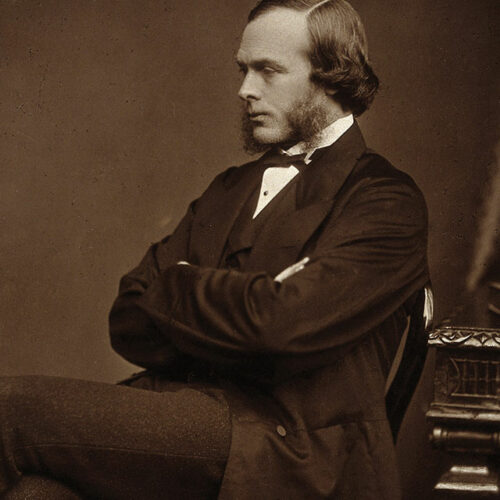

A mere five years earlier, the English surgeon-scientist Joseph Lister, practicing in Scotland, had changed a single patient’s fate, as well as the world’s, by applying carbolic-acid solutions before and after surgery on 11-year-old James Greenlee’s open tibia fracture. As orthopedic surgeon David Schneider writes in The Invention of Surgery, a book hailed as “bold and compelling” by The Wall Street Journal, “what would have been routine amputation was instead uneventful healing, and James was discharged six weeks after injury.”

When the French and Germans took up arms, it was, notes Schneider, m’94, m’95, “the first war in history fought with accurate guns and cannons.” The antagonists’ powerful projectiles impaled filthy bits of clothing deep within ravaged flesh and bone; unlike the French, who still treated open wounds with “greasy salves” and suffered 70% mortality rates from post-amputation infection, German surgeons embraced “Listerism” and doused wounds with carbolic poultice, “with the end result that, for the first time in warfare history, fewer men died from infections from their wounds than from the trauma itself.”

LEFT Robert Koch (1843–1910), pioneering physician who unlocked the secrets of culturing and identifying bacteria. RIGHT Joseph Lister (1827–1912), perhaps the most important surgeon in world history, the physician scientist who introduced sterile technique and antiseptic surgery. Historic photographs and captions from The Invention of Surgery, courtesy the author.

When Koch emerged from his wartime service, during which he had helped prove the efficacy of the breakthrough that allowed surgeons to actually heal their patients—until Lister and his contemporaries, sick people usually improved their chances of recovery and survival by staying clear of physicians and surgeons, Schneider notes—the student of microscopy pioneer Jacob Henle might have been expected to alight in one of Germany’s great academic hubs. Instead, the quiet, studious physician in 1872 settled with his wife and child in the Prussian hamlet of Wöllstein, now a Polish town called Wolsztyn, where they moved into a two-story Gothic structure that became their home as well as Koch’s medical clinic and research laboratory.

Throughout The Invention of Surgery Schneider disavows “granular” theories of medical history, and instead embraces “eureka moments.” The carefully told tale of a cloistered rural health officer throwing himself into solving the deadly puzzle of “woolsorters disease,” otherwise known as anthrax, for example, is presented in a fastpaced and, considering the subject matter, surprisingly charming narrative.

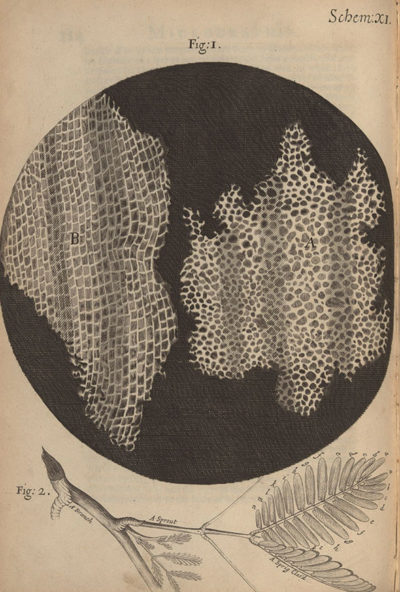

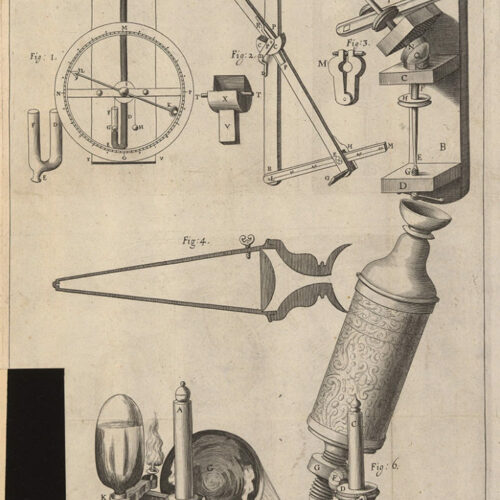

Anthrax arrived in Koch’s village in 1873, spread to humans the following year, and arrived yet again shortly before Christmas 1875, when a frightened constable dropped on Koch’s doorstep the bloated carcass of an animal suspected to have died from the disease. The young physician promptly analyzed the beast’s blood under his microscope. (“Happily for mankind,” Schneider writes, “Koch lavishly drained his bank account” to purchase the best microscopes then available, “obsessively examining tissues and experimenting on animals from his backyard collection.”) Koch saw the same bacteria he’d chronicled in earlier local outbreaks.

Recalling his mentor Henle’s dream of isolating contagious organisms to prove, once and for all, the fatal powers of bacteria, “Koch had a spark of inspiration.” Schneider sets a scene of Koch “exiting the rear doors” of his old home to pull a healthy rabbit from its backyard cage. He acquired a blood sample with a tiny slice to the rabbit’s ear and verified with his microscope that the blood was free of the suspected bacteria. He then injected the healthy rabbit with blood from the carcass delivered to his doorstep. Citing Koch’s “singlemindedness and obsessive focus,” Schneider speculates that he likely endured fitful sleep, and arose the next morning, Christmas Eve, to a full clinic of patients, whom he saw in his upstairs exam room.

Because he visited Wolsztyn on one of eight research trips throughout Western Europe and the United States, Schneider offers the simple yet illustrative observation that the exam room where Koch treated patients overlooks the backyard. In those hours before he could return to the garden, where he later found the rabbit dead and the journey of his life’s work suddenly thrust in motion, Koch had to have been filled with anticipation, and likely paced from clinic to laboratory to window.

Listening to his own moment of inspiration, Schneider thought to look down.

“In the middle of the floor is a slightly angled strip of wood running across the grain of the rest of the floorboards,” he writes. “This is the border between his clinical and research space,” the vestige of a solitary scientist pacing his way through anxious experiments. “In this tiny little town, hours and hours from the closest academic bastion,” Schneider continues, “a self-funded and eccentric young voyager laid the foundation for modern medicine.”

Dave Schneider was an eighth-grader in Manhattan, where his father, J.E. Schneider, chaired the equine program at Kansas State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, when he saw a CNN report on Dr. Frank Jobe. Then becoming well-known among sports fans for elbow and shoulder surgeries that famously salvaged injured pitchers’ careers, Jobe was filmed on the field at Dodger Stadium, mingling with players, and, in that mysterious way that destinies can suddenly galvanize, a sports-mad Kansas boy become obsessed.

“When my dad got home that night, I told him about it,” Schneider recalls from his Boulder, Colorado, home, “and he said, ‘Yeah, Frank Jobe, he’s very famous. He’s an orthopedic surgeon.’ And I was like, ‘That’s what I have to be.’”

Born in Fort Collins, where his father taught at Colorado State University, Schneider spent his early childhood in Nairobi, Kenya, where his father helped found the University of Nairobi’s veterinary school. The family then moved on to Manhattan, which Schneider recalls as an idyllic boyhood haven, with wide-open spaces to roam along with a college town’s intellectual energy.

Schneider joined his father on ranch calls, “getting to be there with the blood and guts in a way that my kids weren’t able to with me. I was literally holding surgical retractors as a little kid for my dad. I was holding knives. I knew how to sew. I learned to use a needle driver 10 years before I got to medical school. The advantages that I had were just ridiculous.”

At Oral Roberts University, Schneider’s creative writing teachers were impressed enough to suggest that he could make his living as a writer; he tucked their encouragement away for later inspiration, but first he headed to the KU School of Medicine, where Schneider spent the summer after his first year doing stem-cell research in the lab of the eminent pathologist and bone researcher H. Clarke Anderson, focused on a type of brain tumor called meningioma. Schneider recalls that when his investigations revealed that the brain tumors in question—donated for his research by neurosurgeons from across Kansas City— secreted proteins that signal and control bone growth, proving his initial theory, the formal, reserved professor “jumped out of his chair,” tears in his eyes.

“It was like I told him I won the Nobel Prize,” Schneider says. “That experience of having an idea that turned out to be true was this incredible moment. That set the path for me.”

Schneider spent a full year in Anderson’s world-class pathology lab following his second year of medical school, and the prestige of placing research papers in important orthopedic journals no doubt helped Schneider land a fellowship with his original inspiration, Frank Jobe, a serendipitous closing of the loop that still delights Schneider. Now established as one of the world’s busiest and most respected elbow and shoulder surgeons, Schneider and his book were featured sources in an April 13 New Yorker magazine story about the advancements and dangers of modern implant surgery, a professional passion that Schneider explores in detail in the final chapters of The Invention of Surgery.

He practices with a large orthopedic surgery group in Denver, and says that rather than constantly grinding to maximize surgical procedures, and revenue, he and his colleagues support one another’s outside interests. “We give each other room,” he says. “We try and be real.” One of the partners owns a distillery with her husband, many coach youth sports, and, five years ago, Schneider began carving out time to pursue his dream of researching and writing a historical narrative about the long arc of modern surgery.

Ever since he was 10, when he pulled down Volume 8—“H”—of his family’s dazzling new World Book Encyclopedia, and became “arrested with wonder” upon finding clear acetate sheets illustrating progressive layers of the human body, Schneider has devoured any worthwhile book about medicine and its history. It is not a hobby he recommends.

“You can get a huge book about the history of surgery that you could never read,” he says. “You would just never be tempted, nor could you physically pull it off, to read the whole thing.”

He wanted a different fate for his book.

Late one evening, a Scottish man was brought to Schneider’s trauma center with a shattered shoulder. After surgery, Schneider met with the man’s wife, also Scottish, and when he found out she was a professional writer, he told her about his book project, in particular his notion that he might include some personal anecdotes to illustrate the education of a surgeon.

“She said, ‘That would lend immediacy to your entire work. You should consider doing it for every chapter.’” It was 2 a.m., Schneider still fresh from emergency surgery, the woman still processing her husband’s injury, and they ended up chatting about writing for half an hour. “Right then and there, I knew: She’s right.”

It’s a huge gamble, even for an experienced author, but Schneider pulls it off. One such passage describes the exhausted surgical resident being stopped on his way out the door, headed for much needed sleep, by the father of a 24-year-old sawmill worker whose four severed fingers had been too mangled to reattach: “Would it be possible take the fingers from my hand and put them on my boy?”

Another vignette tells of a 16-year-old boy, so badly injured in a car accident that killed three classmates that he’d “started to smell like death,” being brought back to the land of the living by a visit from his dog, Honey, a family request that Schneider had been too exhausted to deny, despite his fears of infection. “I told you,” the father said, “there was something about our son and that dog.”

Six months later, Schneider encountered the boy and his father. “Travis, this is one of the surgeons who saved your life.” Travis looked so healthy that Schneider did not recognize him. The father continued: “Dr. Schneider was also there when Honey brought you back to life.”

“Struggling for words,” Schneider writes, “all I can say is, ‘It’s nice to meet you, Travis.’”

The expanse of Schneider’s curiosity and intellect is evident in the starting point he chose for his history of surgery: 5,000 years ago, when people in South America, Africa and Asia all began spinning and weaving wild cotton into material that could be written upon, as with the Egyptians, who transformed their ubiquitous papyrus reeds into durable sheets.

Ancient libraries. Translation. Mathematics. Parchment codices. The printing press. Woodcut printmaking. Moveable type. The Renaissance. The Age of Discovery. Copernicus. The birth, in Venice, of modern glass. The Scientific Revolution. Halley. Newton.

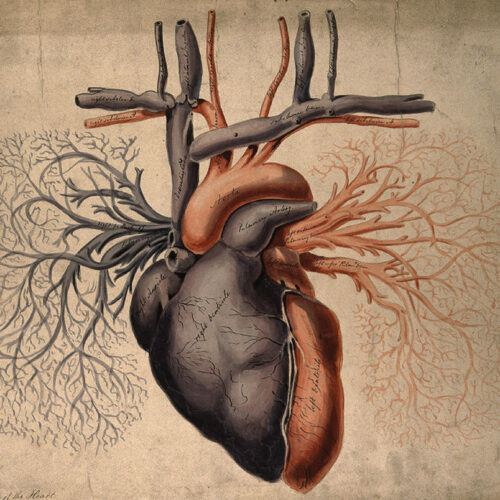

“The rise of surgery, in retrospect, followed a simple pattern: enhanced connectivity among scientists and physicians fueled discovery and communication, small groups of investigators learned how the human body functions, doctors in the 19th century untangled the cellular basis of disease processes, and 20th century surgeons discovered remedies,” Schneider writes. “Each advancement (with its own sub-advancements) rested upon an earlier breakthrough.”

Within the pages of The Invention of Surgery, Schneider describes, in precise detail, the choreography of a modern operating room and the sensation of wielding a scalpel. (“Cutting skin feels like slicing into a fresh peach.”) How it feels to be seated before a 1543 copy of Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica. The “magic in the air” of the University of Padua lecture hall where Galileo once taught, and, next door, the low-ceilinged, heavy-timbered anatomy theatre within which Hieronymus Fabricius passed the baton of the earliest legitimate anatomical study to the Englishman William Harvey.

Physical and metaphorical doors closed to even the most respected academics, Schneider concedes, were opened to him because he is a surgeon, an initiated member of the tribe. He repaid this entrée by diligently and respectfully reporting, researching, reading and writing. For two years, one of the world’s busiest orthopedic surgeons carved out 30 hours a week for his book: 10 hours each Saturday and Sunday, with another 10 reclaimed from late nights during the week or taking the occasional Tuesday off from work. On a typical weekend, he’d arrive at a coffee shop near his Boulder home by 7 a.m., order a large latte and breakfast sandwich, lunch on cheese slices and apples, and power through mid-afternoon with more coffee. Grueling sessions earned the rewards of mountain hikes with his wife, Wendy.

The process will soon begin again, as Schneider dives into his next book, about Joseph Lister, the surgeon who “laid the cornerstone for modernity.” Previous Lister biographies pay too little attention to Lister’s wife, Agnes, Schneider argues, and “completely miss the magic of the Lister story. And that magic is their marriage.”

Schneider says he has already visited every archive in the world that holds their materials, including research papers and personal letters written and received. He’s visited every house that Lister ever lived in, except his birth house, and he and Wendy even reproduced the Listers’ Continental vacations, hiking the same Alpine routes. Despite their fitness and athletic clothes, the Schneiders found themselves “huffing and puffing” on routes that the Victorian surgeon and his wife, clad in formal period clothing, trotted with ease, thanks to their daily walks of 10 to 12 miles.

“Every once in a while in life, the best person is the best person, and that’s Joseph Lister and his wife,” Schneider says. “They’re the most inspirational, magnificent characters in science I’ve ever encountered. Just truly incredible.”

Schneider happily describes himself as a “storyteller,” and clearly he is, but, as with his book, the stories that spark his imagination and wonder are about far more than monumental people doing momentous things.

He describes his father as “a legendary, unique guy, a big, huge, powerful man, but also a very kindhearted guy.” Schneider’s reverential memories transport him back to the day when he saw this towering figure hunched over a tomato plant.

“Why do you like gardening so much?”

He was working on a little tomato plant,” Schneider recalls, “and this great big guy just looked up at me and says, ‘I think it’s like everything in life. I just like to watch things grow.’”

Whether solving anthrax or growing tomatoes, the fundamental formula remains constant: It’s all about the magical moments of inspiration.

The Invention of Surgery

By David Schneider, MD

Pegasus Books, $28.95