Lessons in Leadership

When Bob Dole, ’45, began law school at Washburn University after more than three torturous years recovering from his grievous World War II battle wounds, he lugged a constant companion to every class: his SoundScriber disc recorder, a clunky hunk of hardware that captured his professors’ lectures. He could not take notes in class because his injuries had robbed him of the use of his right hand. Instead, he listened to the lectures over and over, committing much of them to memory.

The SoundScriber, part of the permanent exhibition in the Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics, is Audrey McKanna Coleman’s favorite object in the institute’s vast collection of memorabilia and papers from Dole’s decades of public service to Kansas and the nation. The vintage recorder “encompasses not only his personal experience as a wounded soldier,” Coleman says, “but it also illuminates the dynamic with which he had to attend law school—listening and recording and really fine-tuning his mental capacity—and those skills carried him throughout his career. It tells a wonderful story.”

Coleman, c’01, g’05, the institute’s new director, has devoted nearly a decade to highlighting Dole’s stories. She joined the staff as archivist and most recently served as associate director, collaborating often with Dole and his wife, Sen. Elizabeth Dole, through the years. Coleman officially began her duties as director on Nov. 29. Less than one week later, Dole died on Dec. 5 at 98.

Coleman and Director Emeritus Bill Lacy, who guided the institute’s innovative programs for 17 years, added their voices to the chorus of tributes to Kansas’ favorite son that echoed throughout December—in international news coverage and memorial ceremonies in Washington, D.C., Topeka and Dole’s beloved hometown of Russell. Coleman described Dole as a “towering figure and a bridge to our nation’s past who urged Americans to work together for a better future.” Lacy, who directed the senator’s presidential campaigns in 1988 and 1996, vowed that members of the Doles’ extended family would “do what he would want us to do: continue his life’s work of bipartisanship and public service.”

The institute’s team will dedicate 2022 public programs and exhibitions to Dole, placing special emphasis, as always, on connecting with students. Last fall the institute partnered with KU journalism students, who conducted extensive research and interviews to publish a special University Daily Kansan supplement, “Bob Dole: A life of service,” on the 25th anniversary of his retirement from the U.S. Senate to campaign for president as the Republican Party’s nominee. As part of their research, the students watched several pivotal Dole speeches, and Coleman recalls how the students marveled at his 1996 concession speech following his defeat in the general election.

“Students today do not see enough examples of leadership working in a bipartisan manner, so the project was a real expedition of discovery for them to understand that folks did work this way as a matter of course,” Coleman says. “While we celebrate the senator’s personal legacy as a point of history,” she says, “we can learn from his example and as an institute look for people who are doing that kind of work, showcase and celebrate those people and help KU students connect with them.”

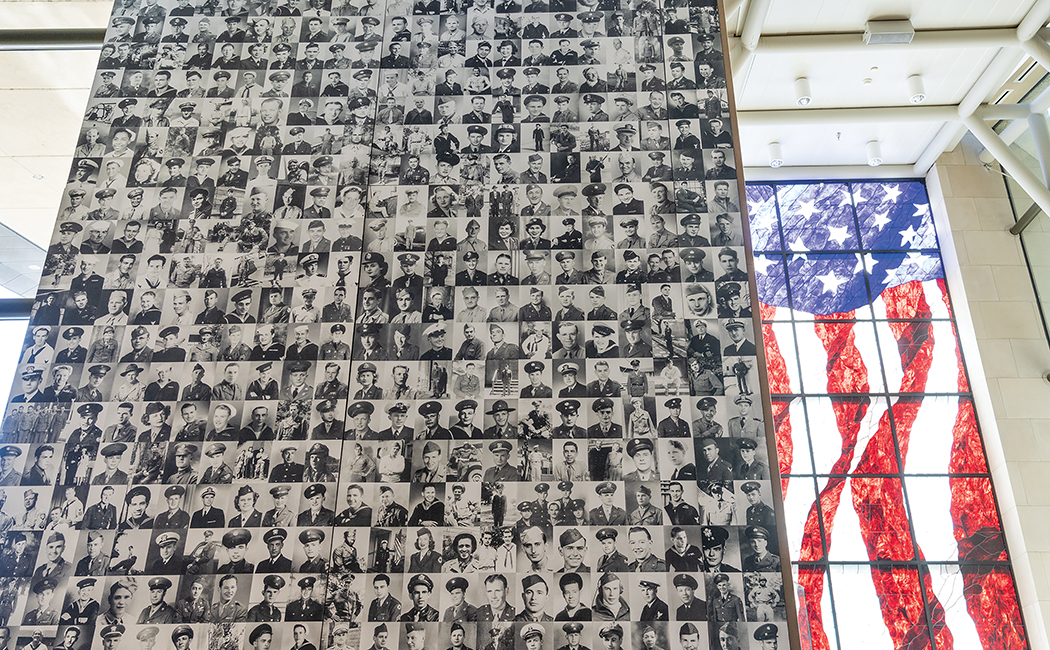

Since the institute opened with fanfare in 2003, visiting speakers and honorees have included elected and appointed officials from all echelons of government, including former U.S. presidents and foreign leaders; scholars of history and politics; journalists and political strategists; and advocates involved in issues past and present. In addition, military veterans remain an abiding presence through events sponsored by KU’s programs in military studies on the Lawrence and Fort Leavenworth campuses and in the soaring Kansas Veterans Wall of photos in the institute’s Darby Gallery. (A new online tribute continues to collect digital photos and bios of veterans from all recent wars).

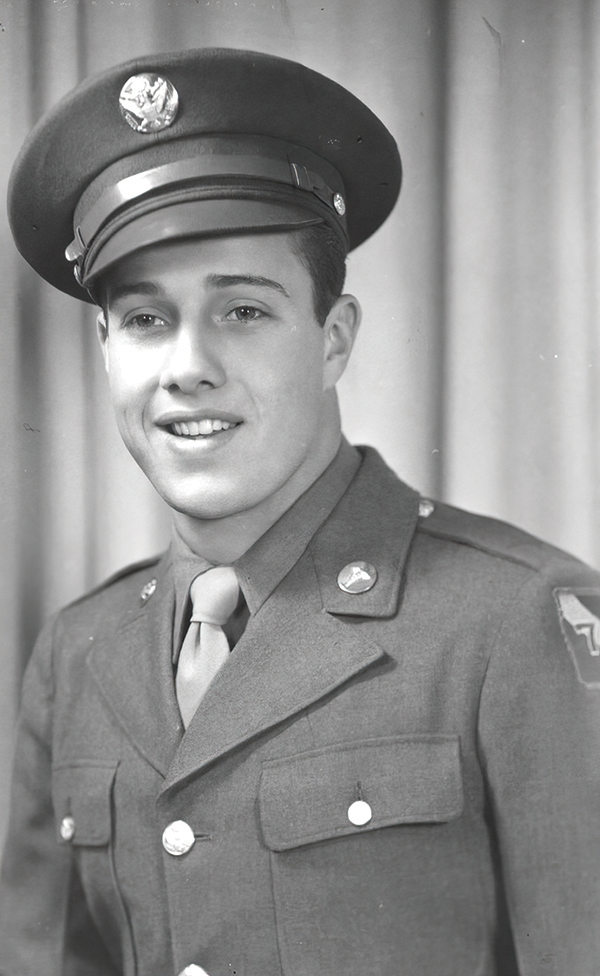

During construction, the planning team invited Kansas families to send photos of their loved ones who, like Dole, had served in World War II. One family sent a photo that is especially dear to Coleman: a portrait of her grandfather, Ray “Bud” Brown, of Emporia, who served as an Army lieutenant, landing in Normandy in August 1944 with the 95th Infantry. He helped liberate the city of Metz and fought in subsequent battles in Germany over 105 days.

Before she began her career, Coleman, then a graduate student in museum studies, often stopped by to see her grandfather’s photo. “That personal connection has made it especially meaningful for me to be here,” she says. “I’ve always had this feeling about him and the Greatest Generation—that I needed to do something to pay them back for the sacrifices they made.”

Her grandfather died at age 98 in June 2013, the same year she traveled to Washington, D.C., for her first visit with Dole. Coleman beams as she recalls meeting him at his law office. “I’m not sure what I expected, but I didn’t expect the warmth and attention that I got from him and his staff,” she says. “It speaks volumes, and it’s reflected in his papers as well—the generosity of spirit that he has, a willingness to listen to who you are and where you’re from and what you’re doing and what you want. Our relationship got off to a great start, and it has been a real pleasure to serve him over the years.”

Today Dole’s records stretch the length of four football fields end to end, Coleman says. Yet to be opened are boxes of papers from his post-Congressional career, when Dole championed the campaign to create the World War II Memorial on the National Mall and, after the monument’s completion, personally greeted countless fellow veterans who visited the landmark.

Since 2017, the institute also has collected Sen. Elizabeth Dole’s records. Coleman first worked with her on the 2016 exhibition and programs marking the 40th anniversary of the 1976 presidential campaign when, shortly after the Doles’ marriage, President Gerald Ford chose Bob Dole as his vice presidential running mate and Elizabeth became a force on the campaign trail, a role then rare for candidates’ spouses. Because Kansas City had hosted the Republican convention in ’76, the institute staged an anniversary event at the Kansas City Public Library, and the house was packed with people sharing their memories, Coleman says. “That is what is really exciting to me—connecting the collections to people who really care, and building a sense of community.”

Memories and lessons of the past, combined with debate of present-day issues, continue to enliven the institute’s programs. Coleman credits longtime director Lacy for his creative approach to connecting with the public through bipartisan events and leadership training for students. “Bill ran a very entrepreneurial environment, which is unusual for a place like ours at a large public university,” she says. “He really gave us free rein to develop online platforms and K-12 programming and exhibits, using the materials we have to tell stories that are unique to this place and both the senators’ legacies.” During the pandemic, the institute’s online programs for young students, including Girl Scouts throughout the region, have thrived under the guidance of public education coordinator Julie Clover, c’10, g’12, Coleman says.

She also cites an important 2015 series, “commemorateADA,” on the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, as an example of the institute’s many collaborations and distinctive role in tracing the trajectory of American politics. Working with community leaders, KU students and Ray Mizumura-Pence, disability history specialist and KU lecturer in American Studies, the institute highlighted mileposts on the long road to the 1990 law, a culmination of Dole’s national leadership in disability rights that began with his first speech on the Senate floor in 1969.

Historic change required 21 years of advocacy, education, negotiation and, above all, vision of a goal more important than the next news cycle or even the next election, Coleman says. “It’s kind of freeing if you think about it, if you can engage with a long-term perspective and break out of short-sighted partisan animosity that we’re just locked into and we’ve come to expect.”

Coleman says KU students’ participation through special events or projects including the ADA celebration, last fall’s special University Daily Kansan and the institute’s Student Advisory Board is vital to the mission of preparing the next generation of public servants.

One of those students is Catherine Magaña, a Wichita junior. As a freshman, she attended the institute’s Party on the Patio, an annual August event featuring a visiting journalist or political strategist, and immediately felt at home. Weekly student discussion groups soon became a mainstay of her schedule, she says. Now a political science major, she coordinates all activities for the group, which includes about 50 students who participate in monthly meetings, special events with visiting speakers and, in election years, voter registration drives. “One of the things I’m most proud of is seeing such a resurgence of student involvement after being online during the pandemic,” Magaña says. “The institute has made me much more interested in public service, perhaps in state or local government.”

Magaña has her eye on law school or graduate school in public administration, and she has gained plenty of experience interviewing notable visitors to the institute. Last August during Party on the Patio, she talked with Catie Edmondson, Congressional correspondent for The New York Times, and on Feb. 3 she interviewed a former student advisory board member who heeded the call to service: Julia Groeblacher, c’10, now a foreign service officer for the State Department who has worked at U.S. embassies in Moscow, Baghdad and Kabul.

Wide-ranging interviews and conversations are central to the institute’s programs, especially as examples of the civil discourse the institute steadfastly encourages, Coleman says. “The only way you can change minds and move forward is to engage with people who don’t believe the same things that you do.”

Her words echo Dole’s declaration during the institute’s gala opening dedication in 2003, when he called for the “kind of politics where conviction coexists with civility, and the clash of ideas is never confused with a holy war.”

For Coleman, the cause is personal. “My kids will be in college in 10 years. I want this to be a place where they want to go, a place that will give them the tools they need to be leaders and citizens for the rest of their lives,” she says. “We’re building the future of the institute—and our country—right now. We have a lot of work to do.”

Dole’s optimism endured, even amid the turmoil following the 2020 election. In early 2021, he wrote a column to be published after his death. On Dec. 6, his words appeared in several national newspapers:

When we prioritize principles over party and humanity over personal legacy, we accomplish far more as a nation. By leading with a shared faith in each other, we become America at its best: a beacon of hope, a source of comfort in crisis, a shield against those who threaten freedom.

Our nation’s recent political challenges remind us that our standing as the leader of the free world is not simply destiny. It is a deliberate choice that every generation must make and work toward. We cannot do it divided. …

Our nation has certainly faced periods of division. But at the end of the day, we have always found ways to come together.

We can find that unity again.