Action as antidote

A Kansas Army wife’s keepsakes recount her trailblazing advocacy, war’s impact on the homefront.

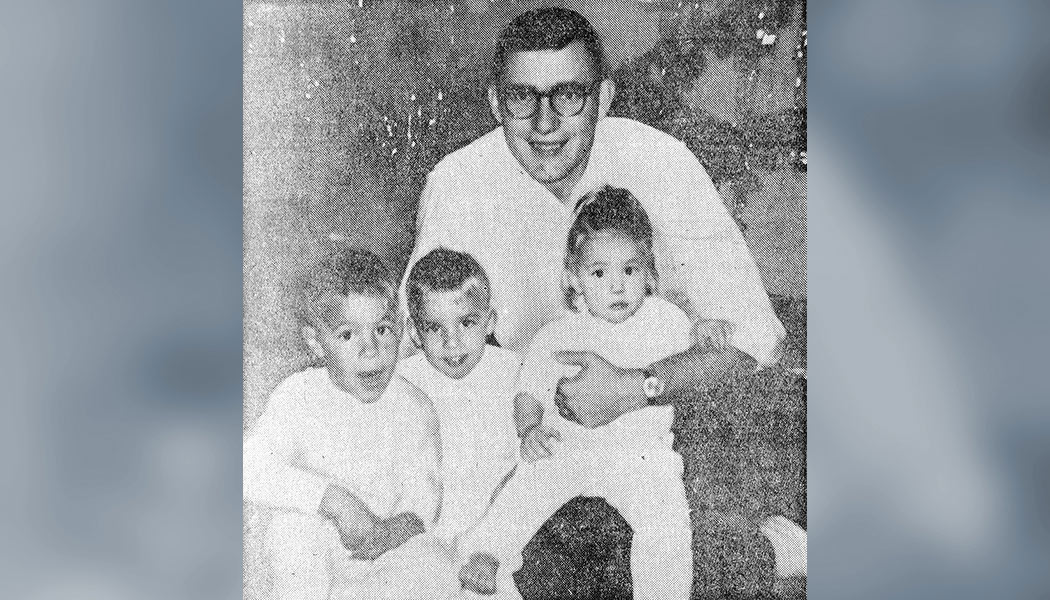

In July 1964, Army Capt. Bruce Johnson deployed to Vietnam to serve as an adviser to the South Vietnamese. In letters home to his wife, Kathleen, Bruce wrote he had no doubt in his return to her and their children, Bruce, Bryan and Colleen.

The conflict and danger escalated, however, and the United States sent in its first combat troops in March 1965. That June, just two weeks before Bruce’s expected homecoming, the family received news that his helicopter had been shot down in the Battle of Dong Xoai in South Vietnam. After radioing that all other passengers on the aircraft had been killed, Bruce vanished. Local reports mentioned a captured soldier who fit Bruce’s description—“a big American who spoke Vietnamese”—so the Army suspected he’d been taken prisoner, but knew nothing more. The wait for any further word on Bruce’s fate would last years, leaving his loved ones suspended in indefinite uncertainty, straddling hope and despair.

“When there is a death, you grieve, there’s a closure, and you can move forward. When a person is MIA, there is no closure. There is grief, but no closure,” says the younger Bruce, c’82, who was 4 when his father disappeared in Vietnam. “Waiting and uncertainty were normal growing up. We lived in it. But it didn’t mean inaction.”

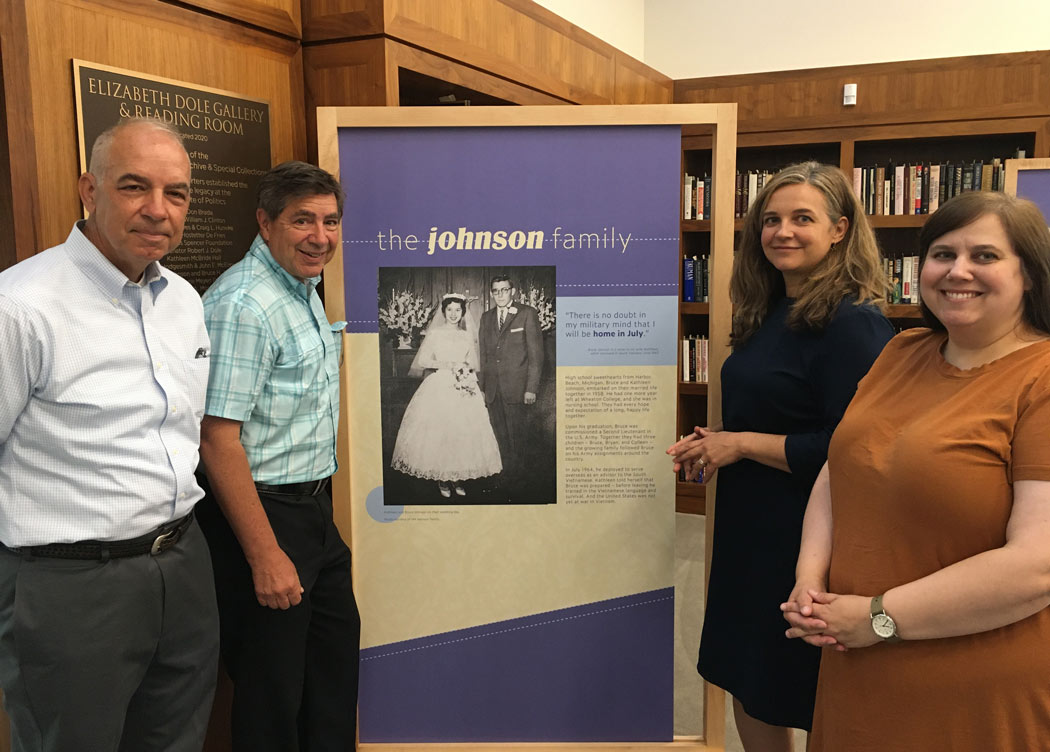

Through a selection of printed materials, the story of Kathleen Johnson’s resolve and the national movement it helped shape unfolds in the exhibition “Missing, Then Action: An Army Wife Speaks Out,” on display through Jan. 26 at the Dole Institute of Politics. The items, saved meticulously by Kathleen over the decades, chronicle her quest for answers about her missing-in-action husband and her subsequent leadership in the National League of POW/MIA Families. A telegram from President Richard Nixon, a patchwork of letters and notes, the tattered address label from a package Kathleen sent overseas to Bruce—returned as “refused”—are among the relics. The collection is at once a love story, a memoir of advocacy, a portrait of loss, and a snapshot of a long, complex war.

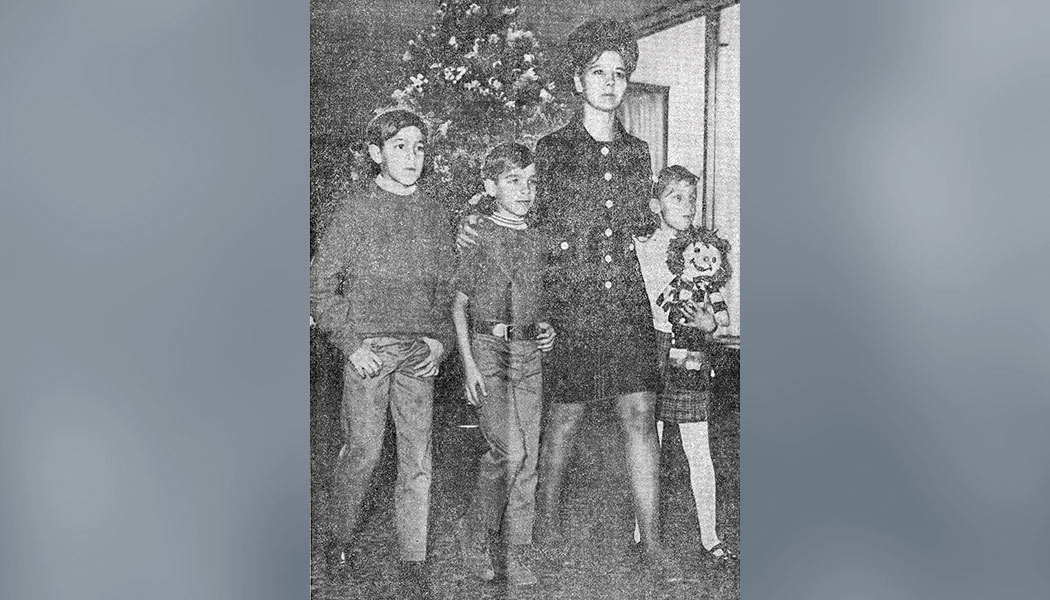

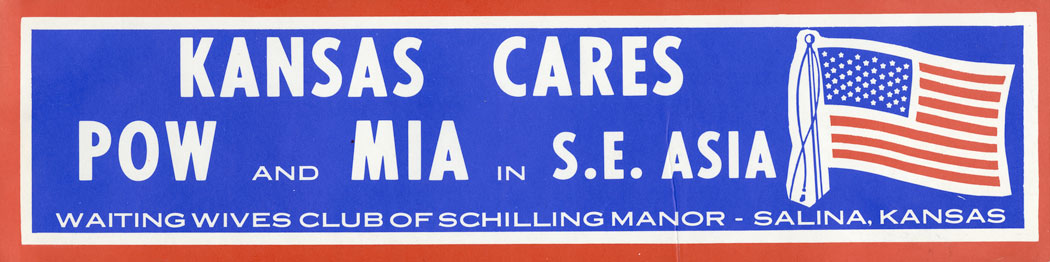

Shortly after Bruce Sr. went missing, Kathleen relocated with her three young children from Michigan to Kansas, settling at Schilling Manor in Salina. In a unique step, the military had converted the recently closed Schilling Air Force Base into housing for the wives and children of soldiers in Vietnam. There, Kathleen joined the community of waiting wives. For the next four years, as she forged ahead amid upheaval, the U.S. government remained publicly silent on the matter of missing and imprisoned servicemen, a posture the men’s families were expected to adopt.

“For many years, the wives did what the military and the government asked them to do, which was to be silent and wait,” says Sarah Gard, senior archivist at the Dole Institute. “These were women who were there to raise families and be supportive of their husbands, then were thrust into a totally new situation. They tried to play by the rules, but came to the realization that that wasn’t working.”

In 1969, several of the wives, including Kathleen, broke their silence, reaching out to legislators and media to try to bring attention to prisoners of war and missing-in-action soldiers in Vietnam. In December 1969, Kathleen was one of 26 wives and mothers invited to the White House to meet with President Nixon and the first lady. The visit was a turning point for the cause’s visibility as well as for the women at its helm, who had the opportunity to meet, unify and strategize. The National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia officially became an organization in 1970, with Kathleen serving as a founding board member. “Missing, Then Action” documents her many efforts to seek answers, raise awareness and appeal for humane treatment of POW and MIA troops, from speaking before members of Congress in Washington, D.C., to collecting signatures in Salina.

“This shows the really personal side of war—not just numbers and battles,” Gard says of the exhibition, acknowledging the Vietnam War’s complicated politics and legacy can make it a daunting subject to confront. “The Johnson family story encompasses a lot of the war, and you can experience it through one person and their family. That can make it a bit more manageable, but no less heartbreaking.”

The younger Bruce remembers the TV coverage of the POWs arriving home in 1973, and watching, gripped, as the men stepped one by one from the plane. “As each one emerged: ‘Is that him?’” he recalls wondering about his father. “I realized that if he wasn’t on that plane, then he probably wasn’t coming back.”

On Feb. 15, 1978, nearly 13 years after Bruce Sr. had gone missing, the Army changed his status to “presumed dead.”

For his namesake, his time at KU, beginning in 1979, was an integral part of healing, allowing him to, he says, “let go of a season behind me and grab hold of what lay ahead.” All three Johnson children attended KU, receiving financial support through Public Law 91-584, which authorized educational assistance for children of missing and captured soldiers. Some of the Johnson siblings’ children have become Jayhawks too.

In fact, “Missing, Then Action” owes its existence to a rainy day in Lawrence in 2017. While visiting his daughter Hannah, c’17, g’19, Bruce, looking for an indoor activity, read about the Dole Institute’s exhibition “The League of Wives: Vietnam’s POW and MIA Allies and Advocates.” When he and Hannah stopped by, Bruce saw his mother’s name in the exhibition and chatted with staff about Kathleen’s ties to the League of Families, laying the groundwork for what has become a close relationship.

In another bit of serendipity, Sen. Bob Dole, ’45, was an early ally of the League of Families and crossed paths several times with Kathleen, one of those being when he asked her to speak to a subcommittee of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in April 1970. Dole’s work on behalf of POW and MIA soldiers is a lesser-known aspect of his public service, which makes “Missing, Then Action” a fitting addition to the institute.

“These exhibits have been a critical part of our developing exhibit program, which strives to highlight untold leadership stories through our collections,” says Dole Institute director Audrey Coleman, c’01, g’05. “The experience of Vietnam’s POW and MIA wives is poignant and thought-provoking, lending us new insights on military service, women’s leadership and patriotic dissent. ‘Missing, Then Action’ is particularly special because it tells the story of a fellow Kansan.”

To create the exhibition, which was made possible by ITC Great Plains, Dole leaders enlisted the eye of architecture and design student Olivia Korte, a’22, who had worked at the institute and been a member of its student advisory board. On her approach to designing “Missing, Then Action,” Korte says: “I tried to pull out bigger themes, and what really stood out to me was the unknown and the waiting. I tried to think of physical ways to represent those.”

The most prominent symbol is a doorway, the place where the gaze often fixes while waiting, wishing for someone’s return. Korte also incorporated Kathleen’s handwriting—a common thread among the items in the exhibition—and touches of 1960s and ’70s aesthetics, her overall goal to make the space “poised and elegant” like the wives themselves, she says.

Kathleen Johnson Frisbie is 85 today and moved from Salina back to Michigan three years ago. She has not been able to visit the exhibition, but Bruce, Bryan, e’84, and Colleen, b’84, attended its opening June 14.

Following their mother’s example of what Bruce calls “living the solution,” Bruce and Bryan have for the past 10 years been deeply involved with two organizations whose work aims to benefit children who are growing up without fathers. Higher Ground at Lake Louise is a camp in Michigan that offers programs and a supportive community for children whose fathers are absent and for single mothers. Psalm68five, founded by Bryan, provides scholarships for children to participate in such retreats. “It’s an opportunity to make a difference in the lives of a bunch of kids,” Bruce says of the endeavors. “It’s very redemptive.”

RELATED ARTICLES

/