Native remains, sacred objects found in museum storage

KU leaders have pledged repatriation.

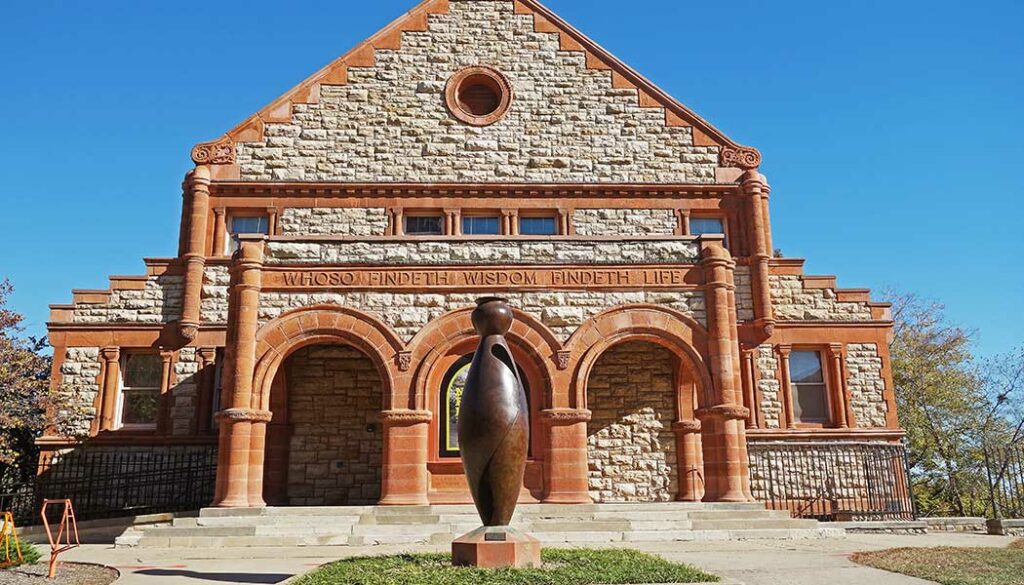

The University in September announced the creation of an advisory committee, which includes representatives from KU’s Office of Native American Initiatives and the Indigenous Studies program, as well as Native staff and faculty, to guide long-overdue repatriation of culturally unidentified individual remains, funerary and sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony stored in Spooner Hall and Lippincott Hall Annex.

In addition, KU will hire a repatriation program manager to coordinate compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and serve as a liaison to tribal nations and various agencies. KU began the search in late October to fill the new position.

In 1990, Congress approved the act to establish criteria for tribal nations to reclaim human remains and funerary objects held by museums. At that time, KU researchers were known to have begun the difficult task of identifying the cultural heritage of ancestral remains and sacred items collected by earlier generations of researchers, but “the process was never completed,” according to campus emails sent by senior University leadership. “The continued possession of these human remains causes great pain for many in the Native community and beyond.”

The University’s failure to comply with NAGPRA was uncovered, according to emails from Chancellor Doug Girod and Provost Barbara Bichelmeyer, by Natural History Museum and Spencer Museum of Art staff.

“As a university, we must continue to give attention to the difficult truth that culturally unidentified individual remains, funerary objects, sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony remain on our campus,” Bichelmeyer, j’82, c’86, g’88, PhD’92, wrote Sept. 23. “The Provost apologizes to our Native community and recognizes the painful process of repatriation. To fully understand the implications of this situation, the University will prioritize the needs of our Native American community while continuing to support, listen, and learn.”

Noting that the University has “grown to be an institution with a distinguished record of research and innovation,” the difficult truth, Bichelmeyer acknowledged, is that research and collection practices of earlier eras “are interwoven with settler colonialism. As we grow, learn and work to right the harm created by those practices, new updates and disclosures come to light.”

Bichelmeyer and Girod have pledged that the University will consult with tribal nations in accordance with NAGPRA; support Native community gathering opportunities and spiritual leaders who can assist students, faculty and staff; audit all collections for updated inventories; move the Indigenous Studies program out of Lippincott Hall; and create institutional repatriation policies and procedures.

“The intent in sharing this announcement,” Bichelmeyer wrote, “is to publicly apologize to tribal communities and peoples, past, present and future, and to apologize to the tribal nations across North America.”

Photo by Chris Lazzarino

/