Road to Recovery

Jolie Lippitt was ready for a new start in 2018. She liquidated her possessions in Madison, Wisconsin. Then she packed what remained into two suitcases and, clutching her preschooler’s hand, boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Topeka.

By then she’d invested in herself to earn seven years of sobriety and move beyond the traumas she carries. Her biological parents, struggling with alcohol use and criminal activity, were unable to care for her or provide a safe childhood. Her mother “couldn’t find a new way to live” and died when Jolie was 10. Jolie’s history includes 11 foster care homes by the time she turned 6, sexual assault, domestic violence, joblessness, substance use and struggles with her mental health.

“I came here with the intention to bloom where I am planted,” she says of her move to Kansas.

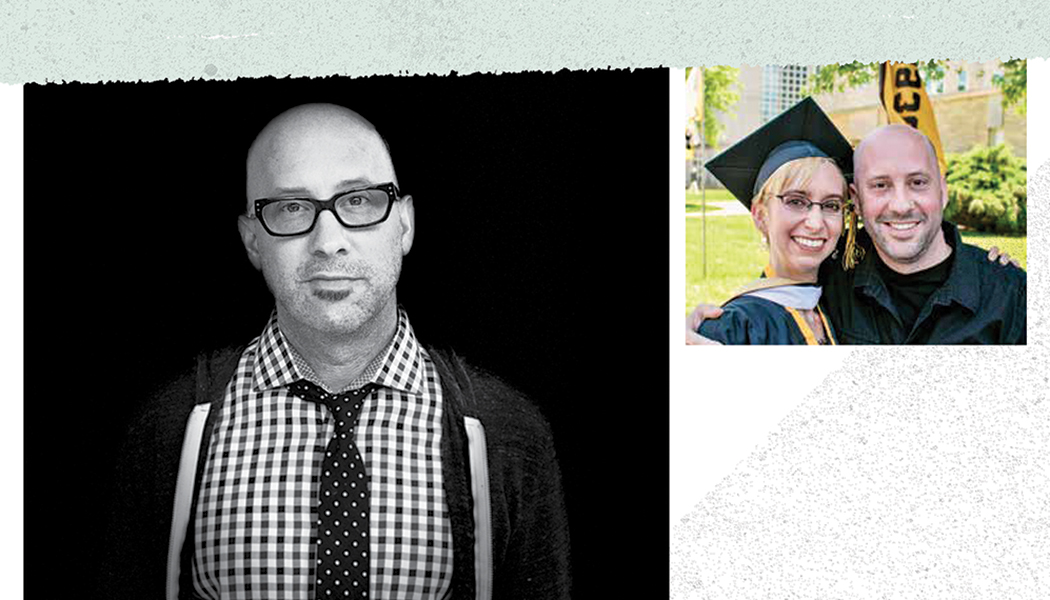

When Heartland Regional Alcohol & Drug Assessment Center (RADAC) took a chance on hiring her despite limited work experience, it provided additional training through the Douglas County Peer Fellows program, in which participants complete 750 hours of work experience and 150 hours of training. Through the program, Lippitt met people like Bruce Liese, professor of family medicine and psychiatry at the KU Medical Center, who helped her apply her lived experiences to assisting others in restoring their own lives.

“Everything from trauma, recovery, to learning how to navigate life: It’s empowered me and enabled me to kind of be that light in the darkness for somebody else,” Lippitt says.

She is one of the scores of people whose lives have intersected with the Cofrin Logan Center for Addiction Research and Treatment since it was established four years ago through a gift to KU. Cofrin Logan Center scientists and students have navigated the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic for more than half of the center’s existence, a time when substance use and deaths attributed to addiction increased dramatically in the United States.

The center’s impact reverberates in the community that forms through the center’s online and in-person peer support groups, which attract local participants and people from across the country. It multiplies through partnerships with community health programs, the graduate students the center trains, and researchers who strive to meet the underserved needs in Black, Latino, Indigenous and LGBTQ+ communities. As the center grows, its activities are informed by the insights and opinions of the people it aims to help.

Treatment for addiction is everywhere, says Dan Logan, c’75, who with his wife, Gladys Cofrin, gave $2 million to establish the center that bears their names. In the past decade, he and Gladys noticed that the number of treatment facilities in Florida had ballooned to meet the rising numbers of people with substance use problems across the country. Little was known about the treatment centers’ track records for success, says Logan, who lives near Gainesville and is a retired emergency room physician and professor of medicine. “People who know nothing about addiction can hang out a shingle and start treating people,” he says of the treatment industry. “It was our hope in creating the center that we could offer treatment that was informed by research to deliver the most effective interventions.”

As a couple who have experienced substance use disorders and long-term recovery, they also wanted to channel their gratitude into helping others.

“This is one of the ways we could give back a little of what we received,” Cofrin says. “We wouldn’t have the life we have now without the gift of recovery.”

Their support helped recruit Richard Yi, professor of psychology, from the University of Florida to KU to direct the Cofrin Logan Center. He has built the center’s infrastructure and staff, developed community partnerships and helped bring in $4.6 million in external funding for research. The center has grown to include investigators and graduate students from diverse KU departments including behavioral science, psychology, communications, social welfare, and architecture and design. The success has inspired Cofrin and Logan to make additional investments, including an endowed chair to be filled in the 2023-’24 academic year, and an endowed operations fund to sustain the center.

The center, which is part of the KU Life Span Institute, is tucked into an office suite on the third floor of the Dole Human Development Center. The walls are adorned with colorful pencil drawings contributed by participants in the center’s local art programs. The laboratory down the hall is the center’s most distinctive feature.

Known as the “bar lab,” the room resembles the neon-lit hangouts on Mass Street, complete with the TV screen for watching basketball games. Plush swivel stools line high-top tables and the large bar, which features plenty of beer taps. Behind the bar are glass shelves stocked with bottles of liquor and wine—or so it appears. Creative mixes of food coloring and water give the contents in the brand-name bottles their authentic look.

Everything about the room is meant to feel like a bar, which is the point of an alcohol administration laboratory, says Michael Amlung, Cofrin Logan’s associate director for training and associate professor of applied behavioral science. The KU bar lab is one of three he has helped develop in the past 10 years.

In the lab, participants are exposed to environmental cues under controlled circumstances. Researchers can study individual motivation to use alcohol, how much participants value alcohol, and the decisions they make about drinking.

Recently, Amlung and his research team added an e-cigarette environment laboratory across the hall. Like the vape shops that dot strip malls nationwide, it includes neon lighting, a vaporizer and tiered rows of vaping devices and nicotine cartridges.

“If we are going to study motivation to use e-cigarettes, we need to temporarily break down the four walls of the lab and try as best we can to make the lab a better approximation of the real world,” Amlung says.

Adding vaping cues to alcohol use also reflects the reality that people often use more than one substance and that there are influences for both. It’s unreasonable to think people can completely avoid all environments that have alcohol and e-cigarettes, Amlung says. Restaurants, grocery stores, gas stations, sporting events and movie theaters can supply those cues.

“We can help people to better recognize when they are experiencing those urges and arm them with skills to adjust their response, so that they aren’t immediately going straight for the urge to use,” he says.

The bar lab studies are just a portion of the research happening among the teams of investigators, postdoctoral researchers and graduate students at the center. Some study the neural mechanisms associated with health behaviors, or explore novel interventions for particularly high-risk populations, such as KU students. For example, investigator Tera Fazzino, associate director of the center and assistant professor of psychology, works with freshmen in University 101 classes to study an intervention based on what students value.

“The insights we gain in this area of research are not about pushing substances away, but about embracing what helps us live enriching lives,” Yi says. “It’s about how we approach life in a way that is consistent with our values and priorities, so we make those a bigger part of our lives, which then tilts the scales so that you’re less likely to engage in problematic misuse.”

Gayla Guthrie remembers her brother Patrick Guthrie, ’99, for his wicked sense of humor and his intense love of his family and KU.

He turned his passions for rock music and culinary creativity into a two-decade career in the restaurant industry. The long hours, job insecurity and exposure to alcohol fueled his substance use problem, which he kept hidden until 2015, when he told his family he was struggling. Several years of treatment, recovery and multiple relapses followed.

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Patrick had just completed another 28-day inpatient treatment program. While his sister had to limit contact with him because of her family’s health vulnerabilities, Gayla always answered his calls, spoke with treatment providers on his behalf and tried to connect him with resources. Patrick ultimately died of complications from alcohol use in June 2020.

Gayla says her brother fundamentally knew that more research is needed to form a better understanding of substance use. That interest prompted the family to create the Patrick Guthrie Hawks for Hope research awards at the Cofrin Logan Center in his memory.

“We need to break through the stigma, shame, guilt and embarrassment that are so prevalent and treat addiction like the disease that it is, like we treat cancer and other life-threatening illnesses,” Gayla says.

Patrick was among the nearly 100,000 people in the United States whose deaths were attributed to alcohol in 2020. The figure was a 25% increase from the previous year. Similarly, from 2019 to 2020, opioid overdose deaths increased 38%, and deaths involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl increased 55%.

Some scientists are exploring possible connections between the pandemic and substance use. They include University of Washington research professor Christine Lee, a national leader in the field who spoke during the Cofrin Logan Center’s seminar series in 2021. She says the changes for young adults that occurred during the pandemic affected mental health and substance use.

“Our work indicates that young adults had concerns and stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic that were associated with specific domains of life, such as finances, work, education and relationships,” Lee says. “These stressors, in particular job distress and social or relational concerns, were associated with poorer mental health early in the pandemic, as well as through the pandemic, and greater alcohol use among college students.”

The pandemic also shaped existing research in unexpected ways. Briana McGeough, assistant professor of social welfare at KU and a Cofrin Logan Center investigator, had planned an in-person research study on a substance use peer support program.

The study was to focus on the needs of people who identify as LGBTQ+ seeking help for substance use. The LGBTQ+ community brings an additional layer to substance use and recovery; individuals may hold critical feelings about their identity because of societal expectations, discrimination, religious background or family relationships, McGeough says.

“It’s fairly common for folks to cope with these self-critical voices in intimate situations by using alcohol or methamphetamines, for example, and unfortunately that can be a barrier to having meaningful connections.”

When the pandemic forced the project to move online, the switch allowed broad geographic representation. Rural LGBTQ+ individuals, who may be more isolated, could interact with people anywhere in the nation. People with physical disabilities were drawn to the meetings as well; an online meeting didn’t present a mobility barrier, and Zoom offers a closed-caption option.

Although McGeough was reluctant to move her research of peer support online, the results have been heartening, she says.

“It’s been overwhelming in terms of how beautifully people support each other. One participant said, ‘I’ve been feeling isolated, but really connected with you all.’ And another participant was moved by that and began weeping. There was a concern that people weren’t going to feel a connection with each other, but they are. From my perspective, that is one of the most important things.”

She’s quick to acknowledge that while moving meetings online may benefit some individuals, it can leave out youths and others who aren’t “out” at home, which may be the only place they can tune in. It also leaves out people with poor Wi-Fi connections or access to the technology.

As the pandemic shuttered businesses, altered child care routines and pushed schools online, it also halted community programs such as those offered by the Cofrin Logan Center. Now arts programs offered by the center’s artist-in-residence, John Sebelius, are back to meeting in person.

On a Monday afternoon at Bert Nash Community Mental Health Center, Sebelius, g’12, enters a room on the main floor and places colored pencils and paper on the tables and desks squeezed into the space. Class participants, who range from millennials to boomers, file in and take their seats. Each is or has been a client of Bert Nash, which offers a variety of mental health, wellness and outreach services.

Sebelius explains the session’s one-hour activity: Draw the home they imagine for themselves three years in the future. It could be a beach shack, a cabin in the woods, or under the ocean, but the key instruction is to make it as detailed as possible. The artists, who may not have had an encouraging experience with artmaking in 10 or 20 years or more, are then asked to identify who lives in the imagined home. What pets do they have? Are there carpet or wood floors? There are no limits, he emphasizes.

As Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldier” ripples from a Bluetooth speaker, Sebelius ambles around the room, talking to the participants about their creations. One woman illustrates a scene with layers of sunny skies, the ocean below, a sandy beach, and a small purple hut in the foreground. A beach ball bounces along the waves. Another woman draws Earth and stars as viewed from the moon. In an hour, the class concludes, and people tuck artworks into bags and backpacks, or leave them for Sebelius to collect.

“We’re challenging people to daydream and physically render it on a sheet of paper,” he says.

The activity is one of a suite of options he offers at Bert Nash, at residential treatment programs in Lawrence and at Warriors’ Ascent, a Kansas City-based program for veterans and first responders struggling with post-traumatic stress or substance use. The art programs dispel myths about creating art and help participants feel comfortable with the materials such as pencils, paint and clay as means of creative expression.

At some locations, participants may be dealing not only with mental health challenges such as substance use, but also with insecure or unsafe housing. Imagining a future home can provide peace, Sebelius says. The exercise also taps into episodic future thinking, an intervention that helps people use the vision of what they want in the future to help address substance use in the present.

Director Yi, who studies episodic future thinking, works with Sebelius to conduct evaluations of the exercise before and after to determine its impact. Overall, the arts programs help people apply what they learn in peer or individual therapy to other areas of their lives, and help them stay engaged, Yi says. “The hard work in a behavioral intervention is the 23 hours a day you are not in a group or in individual therapy. We’re delivering elements of those interventions in ways that are engaging so that someone can do them in their regular, everyday life.”

In addition to the arts programs, SMART Recovery, or Self-Management And Recovery Training, is a staple of the Cofrin Logan Center’s community programming. Professor Bruce Liese, who also is the center’s clinical director, launched SMART Recovery meetings at the Lawrence Public Library in 2019. He leveraged private and county funding to train additional facilitators, including peer trainees in recovery, professionals such as social workers, and KU staff. The effort multiplied into seven weekly in-person SMART Recovery meetings in the county. That year, 229 people participated in those meetings; more than 20% had attended five or more sessions.

When the pandemic shuttered the library and halted in-person meetings, Liese moved to an online format and worked with the newly trained facilitators to offer a local substance abuse hotline. Today the meetings occur both in person and online simultaneously. They draw people from across Douglas County and as far away as New York City.

Thomas is among the participants in the meetings this spring. As he was completing his undergraduate degree in Georgia, he began drinking to suppress the anxiety and panic he had endured since his teen years. Every evening he consumed as many as 10 to 12 drinks to stifle cascading and paralyzing fears about his job and future.

When he arrived at KU in fall 2021, then sober for two years, he no longer had the support systems he had at home. The pressure to achieve in his graduate program began to push his anxiety to new heights, and he began drinking heavily again.

“Even though I kept saying, ‘I’m going to quit, I’m going to quit,’ I would keep having these mental health issues,” he says.

The University’s student mental health services often have a backlog of requests, and it took many weeks for Thomas to be seen by a psychiatrist. In the meantime, an online search of area programs pointed him to SMART Recovery. The meetings provided positive encouragement when he needed it right away, he says.

“It makes you feel supported and less ashamed. It’s no longer, ‘Oh, there’s something that’s really wrong with me.’” Sober since that first week in February, Thomas continues to attend the meetings.

Offering free community programs is part of the Cofrin Logan Center’s commitment to reaching people where they are, no matter their identity, Amlung says. Substance use affects people from all socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, cultural, religious and national backgrounds and identities.

“It also disproportionally affects some groups more than others,” he says. “So while it can affect everyone, there are certain groups of people that are at a greater likelihood of experiencing the negative impacts because of systemic racism, discrimination and policy. What’s exciting about the Cofrin Logan Center is we are trying to use the science to reach some of those groups that are traditionally underserved.”

Yi says that’s one reason why the community programs are so important to the science. People participating in art programs such as the imagined future home exercise can help scientists be informed about how an intervention works in a person’s daily life.

“There has to be a dialogue between research and the real world,” he says. “And it goes both ways: The community can inform the intervention.”

Jolie Lippitt could help make those connections. She is an enrolled member of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, with roots in the Ho-Chunk and the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa nations. When she first worked for Heartland RADAC, she commuted from Topeka to serve in Lawrence, which is home to more Indigenous people than the surrounding areas.

Now sober for 11 years and the single mother of 9-year-old Sky, Lippitt smiles big and warm in a way that disarms her clients and strangers alike. Her easy laughter belies the trauma in her past. Lippitt says she can be the person that she didn’t see growing up: “I often remind myself to ‘be who you needed when you were younger.’

“I help other people, through my own experience, bring into fruition what they want to do with themselves.”

She combines her experiences with the training she completed in February through the county’s Peer Fellows program, which included education sessions led by KU professor Liese.

Bob Tryanski, Douglas County director of behavioral health projects, says four years ago the county recognized that its outreach lacked a critical element, so it joined forces with the Cofrin Logan Center, Bert Nash, Heartland RADAC, LMH Health and other agencies. “It was clear that we needed people with lived experience who want to help people with their lived experiences, and we don’t have a workforce to do the work in systems of care,” he says. “The idea is to create a different type of first responder.”

Lippitt says Liese is an example of someone she wouldn’t otherwise have met because she hasn’t been through university training.

“People like me can get the professional training that the ‘school of hard knocks’ didn’t teach me,” she says of the program. “Peer Fellows absolutely and intentionally exists to create space and create a platform for marginalized people to get trained and be able to connect with communities not only that they serve, but the communities where they are from. There’s power in that.”

Lippitt now serves clients in the Topeka area. She tries to explain that the goal is the restoration of life, with an aim to go from surviving to thriving, and that the process is not linear.

“It takes time,” she says. “Recovery is the process of not giving up.”

Humphrey, j’96, c’03, g’10, is director of external affairs at the KU Life Span Institute.