Kingdom Quarterback: Book explores KC’s past, Mahomes’ ascent

KU alumni Mark Dent and Rustin Dodd deftly weave urban history with Patrick Mahomes’ meteoric rise.

As they pondered the implications of what they’d seen in the Feb. 2, 2020, Super Bowl—a 31-20 triumph by the Kansas City Chiefs over the San Francisco 49ers—veteran journalists Mark Dent and Rustin Dodd ventured beyond overwrought hysteria surrounding all-world quarterback Patrick Mahomes and his potential Chiefs dynasty.

Dent, j’09, a Dallas-based features writer for the business and tech newsletter The Hustle, and Dodd, j’09, a New York City-based features writer for The Athletic who previously spent 10 years writing sports for The Kansas City Star, both grew up in Overland Park. They began a friendship as KU freshmen working at The University Daily Kansan and KJHK, and in the long wake of that thrilling Super Bowl victory, they knocked around a notion that somewhere within the Mahomes madness there lurked an even larger story.

“We sensed that, all right, something’s happening in Kansas City,” Dent recalls. “Like there’s this superstar athlete who has come crashing down to the Earth in a spaceship—that’s how good he is, and Kansas City, where football matters so much, is the perfect city for that.”

At the same time, the authors note, the city itself seemed to be elevating, with downtown upgrades and a new airport, while also taking the first difficult steps in confronting its segregationist history.

“We wanted to figure out how to tell all of that together,” Dent says, “and we found that there was more overlap than we even imagined when we started the project.”

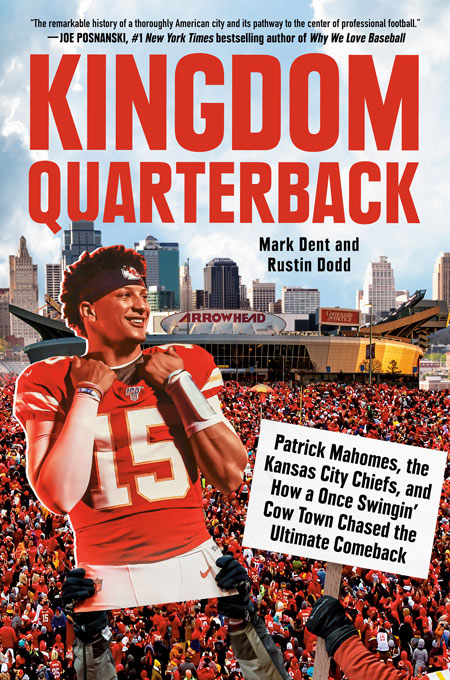

Kingdom Quarterback: Patrick Mahomes, the Kansas City Chiefs, and How a Once Swingin’ Cow Town Chased the Ultimate Comeback, published in August by the Penguin Random House imprint Dutton, achieves its lofty goals, and it’s worth noting that the unlikely concoction has been praised by prolific author Joe Posnanski, the most popular sports columnist in Kansas City before his departure for Sports Illustrated, and Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David Maraniss, who celebrated Kingdom Quarterback as “a brilliant weave of football and urban sociology, popping with illuminating detail and as smart about Kansas City as it is about the meaning of Patrick Mahomes.”

Calling Kansas City “the quintessential American town,” the authors describe their hometown as “a heartland petri dish of every pioneering impulse and social disaster, a stand-in for every town and city that is not quite somewhere, the kind of place that creates the man who creates Ted Lasso. Kansas City’s problems may not be unique, but if you want to understand what happened to the American city, you can start with the story of Kansas City.”

The modern story of Kansas City—and its past and present problems, many of which exist in other urban areas that were eager to follow Kansas City’s once-audacious example—begins with its most ardent civic booster: J.C. Nichols. Still described by some as a visionary, Nichols, c1902, designed and developed the Country Club Plaza and engineered the city’s residential expansion, all while perfecting racial covenants that blocked Black citizens from living in his subdivisions. His methods and madness were even codified by the Federal Housing Administration.

As thoroughly detailed in Kingdom Quarterback, the segregationist system now known as “redlining” pushed minority citizens into substandard neighborhoods where they were denied mortgage insurance, health care and good schools. In Kansas City, the “Troost Wall” became the dividing line, a border not even famous athletes could cross: Kingdom Quarterback tells heartbreaking stories of legendary Chiefs Mike Garrett, Bobby Bell and Curtis McClinton, d’62, all being denied housing in Nichols neighborhoods.

In a creative turn of sleuthing, the authors even dove into the history of the house Mahomes bought as he transitioned from his Plaza penthouse toward family life with his then-fiancee, Brittany Matthews. The house they chose was in Kansas City’s Sunset Hill neighborhood, a subdivision that Nichols launched in 1908.

At a time when cities were unpredictable, Nichols sought control, and began drafting rules for his subdivisions. The first one-page list included minimum construction prices, mandatory space between homes, a ban on apartments, directions for sewer lines and electric poles, and, last but certainly not least, binding and theoretically perpetual racial covenants that automatically renewed before expiring. Citing research by Tulane professor Kevin Fox Gotham, the authors write that the “federal government copied the DNA of Sunset Hill, Mission Hills, and Armour Hills and incentivized developers to paste replicas—in huge quantities at huge profits—at the edges of major metros across the country.”

As unearthed by the authors, the plat for the State Line Road ranch house purchased by Mahomes featured 16 pages of covenants, including, on page 15, what the authors describe as “the familiar all-caps clause”: OWNERSHIP BY NEGROES PROHIBITED.

“I’m hoping that people understand that Kansas City was a really influential place,” Dodd says, “in terms of the way people live and the neighborhoods they live in. There’s a deep influence from Kansas City throughout the rest of the country, and I hope people appreciate that.”

Much lighter fare, too, is found throughout the book, which also serves as the first serious biography—or perhaps biography-adjacent, since, as the authors note, Mahomes in September turns only 28—of the NFL’s most influential new superstar. Mahomes, who rarely grants one-on-one interviews, chose not to participate, but the authors did have access to his father, former professional baseball player Pat; his grandfather Johnny; as well as many former coaches and his longtime trainer. The book relates tales about the family’s early days in East Texas and the many forces that conspired to create the once-in-a-generation talent who would turn Kansas City on its ear.

“There might be some people who like to read about urban planning who might be skeptical about a book with a quarterback on the cover,” Dent says, “and maybe some sports people might say, ‘Mahomes, sure, but what do I really care about American cities?’ But they are intertwined.

“I’m sure the really artsy people are going to kill me for this, but sports are probably the most important cultural piece of most cities in America, and the way that we think about them, the way that impacts how we’re living, certainly has an effect on cities. They definitely go hand in hand.”

In Kansas City, nationwide protests after George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota coalesced around the J.C. Nichols Fountain—on J.C. Nichols Parkway. On June 30, 2020, city officials removed Nichols’ name from both, a move supported by the Nichols family and the foundation that bears his name.

“I think you can definitely take pride in Kansas City, especially in what it can become,” Dent says. “I hope that what we did, and certainly what we intended to do, was to show that there were a lot of people, including J.C. Nichols, who shaped Kansas City into something that is segregated and something that needs a lot of change.

“But I hope that we also showed that there are people right now who are really pushing for that change in ways that we didn’t really see even 20 years ago.”

Asked for his views on Nichols’ legacy, Dent pauses before replying, “I honestly don’t know what I’d say about Nichols. I want to leave that to the reader, frankly.”

Chris Lazzarino, j’86, is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Top photo by Ray Harryman/Pixabay

Bottom photo courtesy of Mark Dent

/