In Her Words

Rebekah Taussig believes the words we use and the stories we tell matter.

For as long as she can remember, Taussig has described her experiences through “angsty, cliché poetry” as a child and “agonizing, relentless journaling” as a teenager. In her 20s she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English, creative writing and literature from the University of Missouri-Kansas City before heading to Mount Oread, where she focused on life writing and memoirs along with disability studies as a doctoral candidate at KU.

Both life writing and disability studies are near and dear to Taussig. Born in Manhattan, Kansas, in the mid ’80s, she was 14 months old when she was diagnosed with a malignant cancer that attacked her spine. Two years of treatments—chemotherapy, radiation, surgeries—gradually took a toll on her young body, leaving her paralyzed from the waist down.

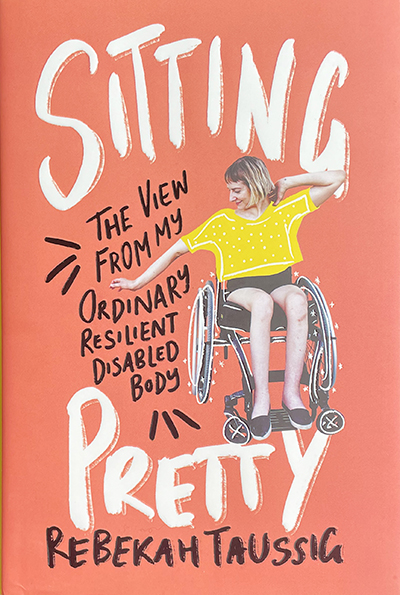

This life-changing event and the experiences that followed form the foundation of her book, Sitting Pretty: The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body, a collection of essays published in August by HarperOne. Taussig, PhD’17, candidly describes growing up in a body unlike those around her, revealing the challenges and complications that she and others with disabilities face each day. The book is a natural extension of the mini-memoirs she began sharing five years ago with more than 44,000 followers on Instagram.

“I think that for a long, long time I have been trying to make sense of the world around me through words,” she says. “That’s just a part of how my brain works. And language is sort of like a way of exploring the world. I’ve had that impulse for a long time.”

The youngest of six children, Taussig moved to Kansas City with her family when she was in elementary school. As she details in Sitting Pretty, her parents, though loving and supportive, made no special accommodations for her in their modest home. Taussig continued to sleep on the top bunk in a bedroom on the top floor the house, pulling her body up without the assistance of ramps or handrails. Several years passed before she received her first wheelchair. All of that, Taussig explains, shaped her youth.

“On the one hand, it made me pretty scrappy and kind of adaptable,” she says. “It made me creative and imaginative in that way. I also think it made me less self-conscious; I was just one of six and just another kid in the whole mix. There wasn’t a lot of spotlight on my disability.

“But I also think that because there was not a lot of careful attention paid to that part of my experience that I went a very long time without actually processing some of the things that were difficult or challenging about it. I kind of blustered into adulthood with a whole part of myself that I wasn’t very aware of.”

As a young girl, Taussig recalls feeling valuable and fully capable of contributing to the group, aware of her disability but not defined by it. “I floated in my own bubble,” she writes, “a universe where everything glistened and glowed and I wore a crown sparkling with jewels. I believed everything I did—the way I moved my body, the way I looked, the roundabout paths I took—was right.”

But as years passed, she grew to perceive herself as a burden on those around her: ugly, weak and helpless. Fueled in part by the fact that she didn’t see girls or women like herself featured on TV, in magazines or in ads, she feared she was “not among those who would be needed, admired, wanted, loved, dated, or married.”

Though she had put pen to paper in some form for years, Taussig discovered a greater sense of direction during a KU creative nonfiction writing class taught by novelist Laura Moriarty, s’93, g’99, who later became her adviser.

“We had the opportunity to write about ourselves, about our own lives,” Taussig recalls. “And I think I basically crammed my whole life story into a 10-page essay, which was never going to be an essay in itself, but she saw what I was doing. … It seemed like something pretty special was happening in that bit of beginning writing.”

Seeing great promise in Taussig’s work, Moriarty encouraged her to continue writing about what she knew best: her own life experience. “I could see that she wanted to do it and that she would be really good at it,” says Moriarty, professor of creative writing and fiction. “Also, it would be really important work that would be valuable to other people. The thing I think is so interesting about Rebekah’s story is it’s universal, it’s specific.”

After taking Moriarty’s class, Taussig began sharing her stories on Instagram. She found the social media platform not only gave her an outlet but also connected her with people who shared similar experiences or wanted to learn from hers. To this day, she’s surprised by the overwhelmingly positive response. “Immediately I was like, ‘What? Why would anyone care?’” Taussig says with a laugh. “I still feel that way a little bit. But yeah, I didn’t really expect that at all. If anything, it emphasized to me that these are ideas that we are kind of thirsty for and a way of thinking that resonates with a lot of people—like, it’s not just me, even though I grew up thinking that surely it was just me who felt this way or experienced things like this.”

Though Taussig had occasionally toyed with the idea of writing a book, the task truly took shape as she encountered limitations on Instagram. “I would sit down to write something in a Google doc, thinking this was going to be something I’m going to post, and then it would be inevitably be like three times too long to fit into that space,” she says, “so I would agonize and hack it to bits and cut two-thirds of it until it fit into that space. I think I was just realizing that I needed to stretch out a bit more, that I needed something like a chapter to explore an idea instead of 2,000 characters.”

In Sitting Pretty, Taussig examines her experiences in great detail: cringeworthy encounters with friends, loved ones and well-meaning strangers; frustrating moments teaching writing and disability studies to high school students at Pembroke Hill School, a rewarding yet often excruciating role she held for the past three years; challenges with accessibility, affordable housing and health care; and the prevalence of ableism, which she explains isn’t limited to “discrimination in favor of able-bodied people,” as Oxford English Dictionary defines it.

“It’s more about systems and structures and values and ideology than it is about a single moment in time,” Taussig says. “I think a lot of times that’s what ableism is reduced to. Like, ‘You said that word, you’re ableist,’ or ‘You took that parking spot, you’re ableist.’ And maybe that’s true, but I think if we reduce ableism to that, we’re missing so much more of what needs to be addressed and changed.”

Moriarty believes that part of what makes Taussig’s writing so appealing is her ability to look at her own story objectively while still considering others’ perspectives, a skill Taussig honed on Instagram and continues in Sitting Pretty. “She takes a hard look at things that are difficult and she doesn’t sugarcoat them or say, ‘That’s OK,’ but she finds her own way through them,” Moriarty says. “She rejects the typical story. She rejects it and strongly emphasizes her own. And that is what is so valuable to me as a reader with her work.”

Since the release of Sitting Pretty, Taussig has gained national attention, appearing in Forbes and The Guardian as well as Time magazine, which featured an excerpt from the book. In October, she was invited to participate in KU’s virtual celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, featuring internationally recognized disability rights leader and longtime activist Judy Heumann. Taussig moderated “Where are the Disabled Artists?” a conversation with Heumann and other notable guests about the representation of disability in the media.

As the Zoom discussion began, Heumann held up a copy of Sitting Pretty. “Go out and buy it,” she said enthusiastically. “I did.”

Last May, shortly before the release of Sitting Pretty, Taussig began a new chapter in her life story: she and her husband, Micah, welcomed their son, Otto, into the world. Though motherhood is new, Taussig found herself prepared for it in an unexpected way. “One thing that has really surprised me about motherhood is just how familiar a lot of the feelings and experiences are to disability in a way that I never would have anticipated,” she says. “I feel like my way of being in the world as a disabled person feels very similar to what it feels like to be a mom, which is so weird. Like, who would have ever thought that those experiences would be parallel?”

Much like her experience as part of the community with disabilities, Taussig discovered a sense of solidarity with fellow mothers, bonding over shared frustrations, fears and fatigue. But Taussig also grapples with a different challenge: how she’s perceived as a mother in a wheelchair.

“When someone sees me as helpless as an independent individual and they rush up to help me or think it’s amazing that I’m doing whatever I’m doing, the most that I feel is annoyed,” she says. “You know, like, ‘Oh my gosh, OK, yes, I’m fine. I don’t actually need your help.’ But when somebody sees me as helpless when I’m with my baby, suddenly there is a very real threat there, because not only do you see me as helpless, but now I’m the caretaker of another little human. And if you think I’m helpless, then you think I can’t take care of my kid, and that is a new kind of problem. That is a new thing to have to prove.”

As Taussig has shown repeatedly throughout her life, she finds a way to confront these uncomfortable, painful moments with humor, grace and understanding.

And she challenges others to do the same.