Formula fun

Love of flying is focus of air racer's work and play

Kent Jackson’s best days away from his law office aren’t relaxing.

They’re flying an undersized aircraft barely large enough for his 5-foot-9-inch frame, at up to 250 mph. He’ll end up banking into crowded turns barely 50 feet off the ground.

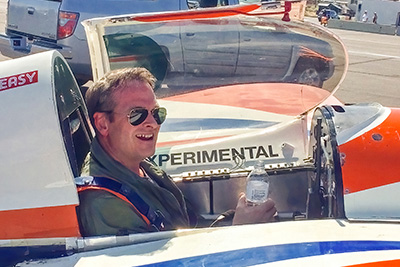

Jackson, c’85, l’88, is one of America’s top pilots in Formula One Air Racing. He took fourth place at the 2021 National Championship in Reno. He’s also done well at international races.

Organized racing of the small planes began about 100 years ago, during America’s aviation infancy. Its early history was marred with crashes as daredevil pilots fed their love of flying and the rush of adrenaline from competition.

Jackson says things are much safer these days, but the draw of Formula One Air Racing stays the same.

“Things get really exciting when you’re passing someone who’s just a foot or two off your wing,” Jackson says. “But I love everything about flying. I can’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t completely fascinated by airplanes.”

Jackson was raised in Topeka, where his father was an ardent hunter and angler. (His sister is Kansas Alumni editor

Jennifer Jackson Sanner, j’81.) While he has enjoyed both sports, his childhood heart was more focused on things like balsa models and remote-controlled airplanes.

At 14, he joined the Topeka chapter of Aviation Explorers, a national program that helps youth learn about flying and careers in aviation.

It was love at first flight for Jackson. When he wasn’t learning about flying, he was working to afford lessons.

“I was always hustling to make money for flying. I sure mowed a lot of lawns and shoveled a lot of snow. Sports never entered my mind,” he recalls. “My life was going to school, working or learning to fly. I don’t think my family was very happy with me [learning to fly], but they saw how hard I was working and didn’t want to get in the way.”

By the time Jackson had passed his bar exams, he was a licensed flight instructor and commercial pilot. The Washington, D.C., law firm he created is called JetLaw and specializes in aviation cases. Jackson often uses his private aircraft for his business and pleasure trips. His wife, Kali Hague, is a licensed pilot and races planes cross-country.

His racing career began in 2016 when he and boyhood friend and fellow pilot Paul Newman partnered to buy “Fast and Easy,” a plane that qualified for Formula One races. He went solo the following year and purchased “Once More.” He’s still racing that plane, although it has undergone quite a few changes.

For every hour spent racing, dozens more are invested in getting peak performance from the aircraft. Like most racing pilots, Jackson does much of the work himself.

Most of the planes are originally fitted with the same 100-horsepower engines found in venerable Cessna 150s. Jackson says there are ways to double the horsepower and rpm from the engines. Changing the wings from wood to carbon fiber can seriously lighten, and toughen, the craft, which is always a goal.

And that speed must be controlled while flying almost within handshake distance of other pilots. Jackson says competitions involve three heats, each with eight airplanes taking off simultaneously.

“These craft are already small, wingspans less than 20 feet and maybe 500 to 600 pounds,” he says. “They’re a thousand pounds lighter than a Formula One race car, but we go a lot faster.”

Love of flying, which enchanted Kent Jackson at 14, remains a focus of his life at work and at play. His law firm, JetLaw, specializes in aviation cases, and his favorite pastime is maintaining and racing his Formula One plane.

Pilots do eight laps around a course that totals about 25 miles. Pylons mark the three tight corners at the end of each mile-long straightaway. Races take about six minutes.

While Jackson acknowledges “a rush” with the quick acceleration and speed of the straightaways, he also thrives on the mental side of the sport, such as planning strategies for passing opponents going into a turn.

He acknowledges there’s the potential for danger, too, but views it more with respect than fear. Improved regulations for equipment and competitions continually bring more safety to the sport. Jackson goes into every race with plans on how to make an emergency landing at any second.

“I’ve had two ‘maydays’ during races,” he says. “Both were non-events because I simply followed the plan. The racing team and I spend months planning and training for any risks that can occur.”

—Pearce, ’81, is a Lawrence freelance writer and former outdoor columnist for the Wichita Eagle

RELATED ARTICLES

/