First Sight

Within the Spencer Museum of Art’s collection of more than 45,000 objects, discoveries always await. A new exhibition, “Debut,” showcases more than 120 works, most of which are on view for the first time since the museum opened in 1978.

Kris Ercums, curator of global contemporary & Asian art, took on the enormous task of selecting objects from a roster of nearly 1,000 little-known wonders.

Winnowing the list began with the most practical consideration: sensitivity to light. “Debut,” which opened Oct. 15 in the Sam and Connie Perkins Central Court and adjacent galleries, will continue for more than a year, through December 2022, so light-sensitive objects, such as textiles and works on paper, could not be included. While “Debut” remains on display, the museum’s closed fourth-floor galleries will be transformed in the final phase of the Spencer’s multi-year renovation.

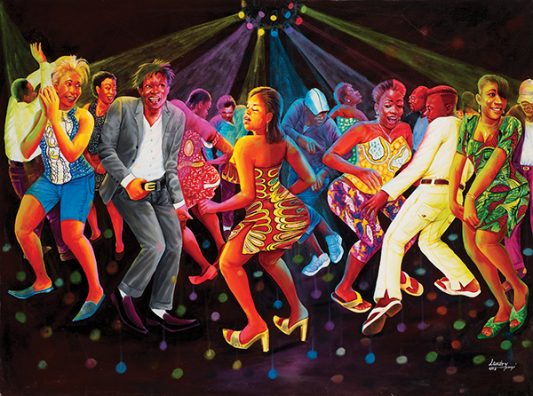

After Ercums eliminated works too fragile for the lengthy exhibition, he surveyed about 500 remaining objects, first sorting them into classical categories: landscapes, portraiture and still life. He then incorporated a variety of 20th-century works into what he calls “global currents,” arranged on the soaring walls of the Central Court like undulating waves to show contemporary art from countries around the world, “from Pakistan to Australia, Myanmar to Costa Rica, showing the real diversity of the Spencer’s collection,” he says.

Amid these never-before-seen works, Ercums and designer Trang Nguyen, head of exhibitions, thoughtfully placed familiar works from the collection—including Thomas Hart Benton’s The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of Lone Green Valley (1934), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s La Pia de’ Tolomei (1868-1880)—that have become sentimental favorites and mainstays for teaching and research. The resulting evocative, eclectic groups, Ercums says, create “new kinds of conversations that come from these more familiar works with these works that you haven’t heard from before. It was about creating new relationships and discoveries.”

“Debut” also served as the project for the Spencer’s 2020-’21 graduate interns, including students in art history, museum studies, philosophy, social welfare, Indigenous studies and education. Led by Ercums and Rachel Quist, g’17, a doctoral candidate from Brookline, Massachusetts, the interns researched the scores of objects that had no previous exhibition records. For each work, students outlined the artist’s biography, along with the work’s date of origin, materials, and cultural, social or political context. The ultimate, most demanding task was to distill their research into concise narratives for the exhibition labels that introduce the objects to the public.

Interns began by asking questions, Quist explains: “At the base level, what would they want to know about the piece, and what would audiences like to know?” During two rounds of peer review and editing over several weeks, the interns continued to refine their research and writing until their labels earned approval.

“Debut” illustrates the invigorating challenges and rewards of internships at the Spencer, where students take on hefty, meaningful projects, “not just the work no one else wants to do,” says Quist, who in the summer completed two years as the museum’s Andrew W. Mellon Foundation/Loo Family Intern in Asian art.

In addition, internships are paid positions, thanks to the support of donors and foundation grants. “It’s a rare opportunity to get a paid internship to do this kind of work,” Quist says. “Professional positions require experience working in museums, but that’s an inaccessible expectation because people can’t afford to work for free. They need to keep food on the table and the lights on. The Spencer program ensures that interns have something to live on, and everyone at the Spencer has made it clear to me that they care about my well-being.

“I gained hands-on experience with a really warm, welcoming group of people. They actually believed in my ability to take on independent projects.”

The museum’s staunch commitment to education, especially through its internship program, holds special meaning for Connie Engle Perkins, d’57, who with her husband, Sam, b’53, has devoted 60 years to collecting art—a passion inspired by Connie’s mentor, Maud Ellsworth, f ’33.

Perkins says she “jumped at the opportunity” to create a new internship for the Spencer’s thriving program. The Connie E. Perkins Endowed Internship in Contemporary Art will support young scholars’ study of the genre that first captivated Connie when Ellsworth, associate professor of art education, introduced her students to the bold, abstract works of German-American artist Josef Albers. Ellsworth also encouraged Perkins to become an art education teacher in the Olathe public schools, where Perkins in turn readily welcomed student teachers recommended by Ellsworth.

Saralyn Reece Hardy, c’76, g’94, Marilyn Stokstad Director of the museum, says the new internship will extend an important legacy. “I deeply appreciate the influence that Connie is so quick to share about the presence of Maud Ellsworth in her life. Maud was a role model for so many people, especially those who loved art.

“Connie’s understanding of the importance of education in the arts and the importance of art in a large university has been very inspiring because she has devoted her life to research of her own collection and the selection of beautiful and significant objects.”

As Connie and Sam traveled to 173 countries, they carefully acquired an extensive collection of art in all forms from many cultures. “We did our own quiet thing in collecting,” she says of their years of study and meeting with artists and gallery owners. “You get to know the artists and follow their careers.”

Their affection for the objects grew stronger with time as their acquisitions became part of their home. Over 60 years, they sold only one piece.

But this summer the couple fulfilled a longstanding promise to give their entire acclaimed collection to the Spencer. The objects arrived in time for more than a dozen to be unveiled in “Debut.”

Perkins praises the museum’s strong commitment to education through internships, academic partnerships across KU and varied public exhibitions and programs. “That is exactly why we offered our collection to the Spencer,” she says, “because they will use it for education of the future generations.”

The gifts of the collection and the internship are the culmination of the couple’s long relationship with the museum as benefactors, including their leadership gift for the first phase of the Spencer’s renovation [“Partners and patrons,” issue No. 5, 2016].

Reece Hardy praises the couple’s keen knowledge and precision as collectors. “Connie and Sam are unusual in their diligence about documentation and research and understanding of their collection,” she says. “The collection comes with their care for it.”

These newest items in “Debut” include a stunning variety of works: breathtaking sculptures in the Central Court; small, fanciful bronze figures and ceramics in the museum’s Cabinet of Curiosities; and, in front of the wall of glass that looks out onto lush Marvin Grove, exquisite, black-leather chairs that appear designed with the Spencer in mind.

As curator Kris Ercums led a tour of “Debut” during the jubilant opening reception, he assured hesitant visitors that, yes, it’s really OK to sit in the chairs. “It’s art you can interact with,” he declared with a laugh.

Just another way in which the Spencer feels like home.