Danny and Goliath

In April 2019, Danny Caine overheard a customer at Lawrence’s Raven Book Store saying that she could buy a hardcover online for much cheaper than his store was selling it.

Pick up a book, hardcover or paperback, and somewhere, usually inside the front jacket or on the back cover, you’ll find its price clearly marked. That price is set by the publisher, which also sets the discount booksellers receive when they purchase the book to resell in their store. The difference between the cover price and the discount (minus freight) is the bookstore’s profit.

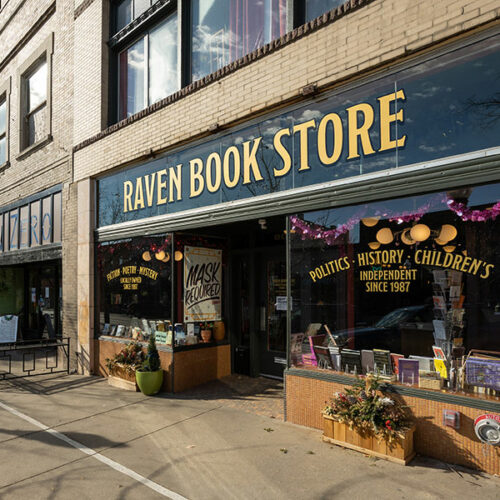

Caine, g’17, who leads the third ownership team to run The Raven since it was founded in 1987, was selling the hardcover for its list price of $26.99. The customer said she could buy it online for $15, and presumably she did.

Such exchanges between bookseller and bookbuyer no doubt happen daily in America’s 1,900 independent bookstores. A common refrain in the Amazon Age, the sentiment also rings familiar to anyone who operated an independent bookstore in the 1990s, when corporate megastores like Borders Books and Barnes & Noble reshaped the publishing industry by squeezing small booksellers across the United States—including in Lawrence. In 1996 Borders announced its intention to open a 20,000-square-foot store not merely in Lawrence, but on a downtown corner practically next door to The Raven’s 1,200-square-foot store at 8 E. Seventh St. Local champions of independent bookstores and small businesses widely bemoaned the move. Raven supporters figured the Borders announcement was the beginning of the end for their cherished store, but they rallied to support it, and as a result the occasion of Borders’ grand opening—Dec. 6, 1997—proved to be The Raven’s biggest sales day to that point. Within five years the entire Borders chain had collapsed in bankruptcy, the Lawrence store closed, and The Raven soared on.

Still, there were challenges for a small store going head-to-head with a corporate chain.

“The problem with Borders was that it was 150 feet from our front door,” says Pat Kehde, g’80, who founded The Raven with Mary Lou Wright. “And so people would come in and say, ‘Do you have this book?’ No, but we can order it for you. They’d say, ‘Well, no, I’ll just get it at Borders.’ OK. What could we say?”

What could they say, indeed. Running an independent bookstore (or any small business) means dealing with a formidable to-do list. In The Raven’s case, there are books to order, boxes to unpack, shelves to stock, special orders to track, customers to ring up, plants to water, phones to answer and cats to feed. A business owner could be forgiven—encountering snark about the bargain and convenience of online shopping—for swallowing hard, forcing a smile and politely saying, “Thanks for stopping by,” before moving on to whichever task demands attention next.

What Caine did instead was compose and post to the store’s Twitter platform a thoughtful response that began, “Our mission is not to shame anyone for their shopping practices, but we do feel a responsibility to educate about what it means when a new hardcover is available for $15 online.” The thread explained the wholesale discount that publishers offer a small shop like The Raven (46% off the cover price), and how larger booksellers like Amazon get larger discounts and use revenue from other, higher-margin products to make up for losses they incur when selling books below their already deeply discounted cost. To sell a $26.99 book for $15 would net his store 43 cents, Caine noted. “We have 10,000 books in stock. If we sold every one of them with a 43-cent markup, we’d make enough to keep the store open for about six days,” he wrote. While conceding that it may be fair for high-volume booksellers to reap higher discounts, he also reminded readers of all the things that giant online retailers have no interest in doing: bringing national authors to town and working with local writers, emerging artists and local cultural organizations to enrich community life, for example. Creating a safe, welcoming space for people to while away an hour or three. Feeding store cats. Or paying taxes.

Caine’s Twitter tutorial went viral, generating more than 20,000 retweets and quotes and nearly 50,000 likes. Booklovers nationwide chimed in to bemoan the loss of their own local stores, to pledge their determination to order from The Raven’s website, and to share their own observations about the prospects for independent bookstores and their customers if e-commerce giants are allowed to dominate. Cautioned one Twitter user, “If people keep it up, one day that big online retailer selling hardcovers for $15 will be choosing all the books. They will be publisher, editor, distributor. Total control.”

Caine says he was already talking about these issues with other booksellers and had been thinking about how to broaden the discussion to include people outside the industry. Then came the surprising response to his tweets. “I was telling the story of a single incident that happened in the store, and all of a sudden it became relevant,” he says. “That was the first time I realized there was an audience for it. There was a community it resonated with, and just through the sheer luck or randomness of what goes viral, they were listening to me. So it was like, well, there needs to be someone saying this, and if it’s going to be me I better do it right. For the first time, I felt a lot of eyes on me and a lot of eyes on The Raven, and it was important to not waste the chance.”

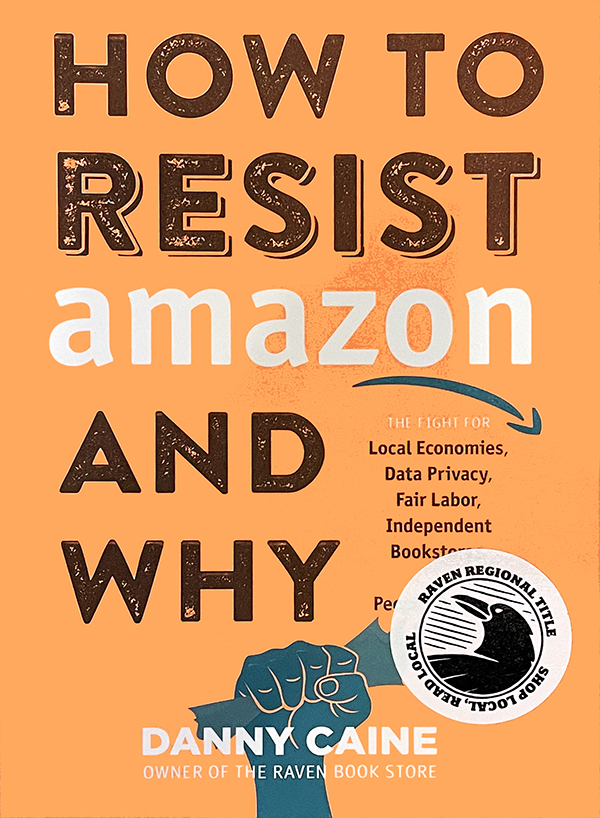

So began an unlikely march to national prominence for a local shop and its somewhat unlikely proprietor, a poet who first dreamed of owning The Raven while working there part time as an MFA student at KU, a newcomer to Lawrence and to the boom-and-bust world of retail who decided to use his store’s social media bullhorn to point out the drawbacks of our wholehearted embrace of online shopping. Along the way, Caine wrote a book, How to Resist Amazon and Why: The Fight For Local Economies, Data Privacy, Fair Labor, Independent Bookstores, and a People-Powered Future, an ambitious survey of Amazon’s dominance of online retail and infrastructure and the tangle of issues it raises in both the virtual and real worlds. As the pandemic transformed how we shop and fattened Amazon’s bottom line, The Raven not only survived the economic upheaval, but also actually beat its competitor (for a while) at its own game, coming out of a yearlong COVID shutdown stronger than it went in, with a greatly expanded trade in online orders and a new, larger store in the bustling hub of Lawrence’s Massachusetts Street. That it would do so while dealing head-on with controversies and the competing interests of an array of “stakeholders”—city leaders, merchants, developers, publishers, consumers, corporate competitors—puts it squarely within a legacy of community engagement that dates back to The Raven’s face-off with Borders, and earlier still, to the store’s earliest days.

Soon after joining the staff part time, in 2015, Caine recalls, he heard the story of that “mythical first Saturday” when Borders’ grand opening led to a Raven sales boom. “That was a lot of effort and smarts from Pat and Mary Lou,” he says. “Navigating that successfully must have been a monstrous feat. But it built into the store this David versus Goliath ethos that gave the place a feisty feel that definitely attracted me. It was like, ‘If it can survive that, what else can it survive?’”

Kehde and Wright began batting around the idea of starting a bookstore in 1984. Friends from their days at Scripps College in Claremont, California, they often played tennis together in Lawrence, where Kehde directed KU Info at the University and Wright was business manager for the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. “We began talking about the books we loved, especially mysteries, and how we would enjoy working with books and people,” Kehde wrote in a history of the store. Lawrence had no B. Dalton and no Waldenbooks, the major national chain booksellers of the era, and none of the town’s handful of small bookstores carried a good selection of mysteries or offered many author events. They saw a niche in the local market they could fill.

But first they had to help save downtown.

In the mid-’80s, after a bid to build a “cornfield mall” in Lawrence failed, developers turned their attention to Mass Street, proposing a sprawling mall that would raze several buildings and close downtown’s main drag between Sixth and Seventh streets. “They were going to build right up to the door of Liberty Hall,” is how Kehde remembers it. “The ghastliness of it was unbelievable.” She rallied the community in a successful fight to stop the project, which also contributed to the election defeat of city commissioners who backed the idea. The campaign helped reinforce city planners’ determination to treat downtown as a jewel worthy of preservation.

In 1996 The Raven owners found themselves at the center of another battle after Borders announced plans to demolish seven buildings, including a 98-year-old structure at the corner of Seventh and New Hampshire that once housed a livery stable, to make room for a store and parking lot. The location was considered within the environs of the Eldridge Hotel, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Preservationists opposed the plan. “The Borders War,” as the media dubbed it, ended in compromise: Borders agreed to incorporate the stable’s north and west exterior walls in the building, downsize square footage and decrease parking.

“The political fight, in which The Raven played a part, did not succeed in keeping Borders from the corner of Seventh Street and New Hampshire Street,” according to Kehde’s history. “But the political actions and protests had lasted for many months, and numerous articles had appeared in the Lawrence Journal-World. All the agitation was invaluable in helping raise public awareness about The Raven and other issues. Now in the minds of the public and many of our customers were ideas about the importance of supporting our local economy by shopping locally, the value of the personal relationship between shopkeeper and customer found only in locally owned stores, and the aesthetic standards for new buildings being built downtown that were consistent with the small footprint, zero setback, and other architectural standards already existing in the city’s codes.”

That year Caine was 10 and living in Solon, Ohio, “a suburban dream place,” as he calls it, “with the McMansions and the good school districts.” His local bookstore was a Borders. Not until he went to college, in Wooster, Ohio, did he discover the charms of a downtown business district with local restaurants, funky coffee shops and an independent bookstore that became his favorite hangout: Books in Stock.

“I’d go downtown and spend hours in there,” he says of the classic, overstuffed, dusty shop. “I fell in love with the place.”

In 2014, when he and his wife, Kara, g’16, came to Lawrence to rent an apartment before starting graduate school at KU, Caine fell in love with what he found here, as well.

“Mass Street cast its spell on me,” he says. “And the more I lived here, the more I realized that there’s intention behind that. You don’t have four blocks of main street that are predominantly small businesses by accident. There have been people fighting for a space for that stuff in Lawrence for decades. That’s community work, that’s advocacy, and a lot of work has to happen to make that possible. And I think that the original Raven owners were a large part of that.”

The scouting trip included a visit to The Raven, and after he moved to Lawrence that August, he was in the store often.

“I began trying to work here immediately; it was kind of a campaign,” Caine says with a laugh. “It was eight months or so of becoming a known quantity and getting to know the people who worked here and becoming part of the scene. It took awhile, but I got there.”

By then Heidi Raak owned the business, having bought it from Kehde and Wright in 2008. Kehde still worked a few days a week, and she and Caine often shared the Saturday morning shift. In How To Resist Amazon and Why, a chapter called “On Delights” lists some of the sweet moments of bookstore life, including this charmer:

“When you have the Saturday opening shift and the store is quiet and the cats are eating and the sunlight slants in through the windows. A sunny Saturday morning is the best time to work at a bookstore. When I was still part time at The Raven and I had the Saturday morning shift I used to dream about owning the store.”

“I mean, for a graduate student, he was a different cat, you know?” Kehde says. “For him to be reading and talking books to people and also going to graduate school and doing all the reading you have to do and writing papers and all that. But he’s a guy with a lot of energy and a lot of love for the written word. And that’s really where it begins, I think.”

“Many people who love books and want to think about making a life in books at the very least kind of idly dream about working in a bookstore or owning a bookstore,” Caine says. “And The Raven turned into an opportunity, pretty quickly, for that dream to become real. It was a fantasy, but then it became a goal.”

After doing his research (including a visit to bookstore boot camp that sounds a lot like one Kehde attended in the 1980s) he decided, in summer 2017, to go for it.

“My plan was that, on the surface, you shouldn’t notice much difference, because the in-store stuff was working. I wanted to keep what the customer sees as close to The Raven’s history as I could, while making everything underneath more efficient for the staff, to kind of introduce the capacity to get busier and grow.”

Growth came, much of it driven by Caine’s savvy approach to social media. In 2019, for example, the store experienced what he called “a bit of Christmas in July” after Shea Serrano, a bestselling author whose 300,000 Twitter followers form a stalwart “fan army,” tweeted his support of striking Amazon workers and challenged fans to nominate a local store to receive book orders on Prime Day. Caine nominated The Raven, Serrano made the first purchase himself, and orders flooded in. The store racked up more online sales in a day than in all of 2018. Afterward, Caine felt inspired to turn a secondhand trophy into a tribute to Serrano and fans—which led to more social media buzz and (he hoped) more visits offline.

“We’re happy to sell books online, but the best Raven experience is in-store,” Caine told Kansas Alumni. “Come see the trophy, but once you’re here you’ve got the book smell, and the cats and all the comfy chairs.”

That was July 2019. In September the Midwest Independent Booksellers Association gave Caine its Bookseller of the Year Award, praising his work to organize inclusive events that give a platform to under-represented writers and bring the entire community together—singling out, among other things, his collaboration on a speakers series with The Commons at KU and his planned launch of Lawrence’s first large-scale literary series, Paper Plains, scheduled for April 2020. Then in March COVID changed everything.

The Raven closed its doors for 15 months, but found creative ways to keep its booksellers employed while keeping them safe. Online sales (again driven by the store’s strong social media presence) ramped up, and Caine pushed aside shelves and emptied tables to convert the browsing floor to a shipping hub. He set up a shelf outside to offer free books donated by the Lawrence Public Library, and started curbside pickup and, later, a walk-up window where readers and booksellers could interact. He even began offering free same-day delivery in Lawrence, using his own car to make the drops, at a time when Amazon had declared books “nonessential” and stopped delivering them at all.

“It’s kind of fun to drive around town every afternoon like a book Santa Claus,” Caine said. “People need stuff to read. I don’t know if books are essential, but they certainly help when you’re stuck at home and bored. Stuck at home with nothing to read is a special kind of nightmare.”

Sally Zogry, executive director of Downtown Lawrence Inc., says Caine was at the forefront of downtown merchants’ adaptation to COVID, just as he has been in the battle against the e-commerce giants.

“He has such confidence, such a firm belief in the importance of small, locally owned businesses to stand up against the Amazons and the other large retailers, both online and brick-and-mortar,” Zogry says. “There are those folks who just kind of throw up their hands, and why not, right? ‘How am I ever going to compete with that?’ He’s been really inspirational in the way he has told his story, and he was kind of the first to start to change the landscape of how you react to this economic shutdown that none of us have lived through before.”

During the pandemic, Caine learned something about his sunny little store on Seventh Street. “When we were just selling books it worked; when we were just shipping books it worked,” he says. “But it was pretty clear that space wasn’t going to cut it for both.”

He started searching for a new location and settled on 809 Mass St. After months of renovations, The Raven moved into its beautiful new home in August, with greater accessibility (no more steps), twice the square footage, twice the walk-in traffic and sales growth that Caine characterizes as “explosive.”

“He’s gotten to this bigger space, and that’s a huge commitment, right?” Zogry says. “He’s done a beautiful job renovating it, which takes money and commitment. 2020 comes along and yet he’s still able to expand and is doing better now than he was before. That’s really pretty amazing.”

After his Twitter treatise on the high cost of cheap books took the interwebs by storm, Caine pressed his argument about the threat Amazon presents to indie bookstores, small businesses and thriving downtowns.

He began by penning an open letter to World’s Richest Man and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. (“I needed a thesis statement,” says Caine, who taught high school in Ohio between college and grad school. “If I’m going to argue, it needs to be clear exactly what I’m arguing and why, right? It’s the English teacher in me.”)

Analyzing the retail giant’s dominate-at-all-costs strategy, which has many small-business owners calling for it to be broken up, nationalized or shut down completely, Caine made a more measured request: Level the playing field by setting prices fairly, rather than selling books at a loss to hook Amazon customers on Prime subscriptions, Kindles, Alexas and other high-margin products and services.

“A Letter to Jeff Bezos from a Small Bookstore in the Middle of the Country” drew no response (Bezos never took Caine up on his invitation to tour Lawrence’s thriving downtown and enjoy a slice of pie—“my treat”—at Ladybird Diner), but it did make clear that Caine is no Luddite. While acknowledging tech’s ability to “disrupt” old ways with new efficiencies, he argued that the battle between Silicon Valley and Main Street isn’t just a low-stakes tiff between competing businesses—healthy competition is a good thing, he contends—but is a corporate power play meant to squeeze small businesses out of the marketplace, robbing towns of the benefits these local stores bring. The Raven and businesses like it are go-to donors for the goodie baskets and gift certificates that power charity silent auctions; the readings, signings and other events they host help weave the vibrant social and cultural fabric of these towns. “We’re not relics. We’re community engines,” Caine wrote. “For so many places, the loss of an indie bookstore would mean the loss of a community force. If your retail experiment disrupts us into extinction you’re not threatening quaint old ways of doing things. You’re threatening communities.”

A friend urged him to turn the letter into a zine, so he printed 50 copies to sell in the store. After he posted about it on Facebook, Microcosm Publishing, a small, eclectic house in Portland, Oregon, offered to distribute, and before long called with surprising news: The 16-page tract he put together in an afternoon was selling like crazy. Did he want to expand his ideas into a full-length book?

How to Resist Amazon and Why was published as a 128-page paperback in March 2021 and has since sold more than 10,000 copies. A love song to “the idea of the Book with a capital B,” it’s also a manifesto on the importance of small businesses, local economies, community building, fair wages and humane employment practices. Amazon is posited as both unprecedented (“There has never been a company as big, powerful, and pervasive” Caine writes) and as the newest twist in a old plot. (“Amazon is a continuation of the story begun when Walmart and other megastores began their rapid spread … the latest link in a chain of threats to the American retail small business, from shopping malls to chain megastores to online e-commerce giants, each acting in their own pernicious way to destroy the American downtown.”)

With its one-click ordering, free shipping and quick delivery, Amazon has created a friction-free buying experience that lessens the chance that shoppers will think much about the ramifications of their purchases—a big mistake, in Caine’s estimation. “Before we let Amazon become as big as it wants to be,” he argues, “we must investigate what it stands for.” With chapters on Amazon’s impact on book publishing, its aggressive pursuit of tax abatements, its treatment of warehouse workers and delivery drivers, and its deep entanglements with the U.S. Department of Defense and local police departments, How To Resist Amazon and Why is one indie bookseller’s attempt to help readers do just that.

“The book is really good, and it really does outline the situation, particularly the legal situation, really well,” says Dennis Johnson, co-founder and co-publisher of Melville House, an independent publishing house in Brooklyn, New York, who joined in Caine’s virtual book launch in March. “It’s not a shallow, ‘Oh, let’s fight Amazon.’ It’s actually a detailed description that I think anybody who wants to do something should read. And it does nail the fact that the problem is legal. We have laws. Amazon for 20 years didn’t pay taxes! Kids, don’t try this at home. You won’t get away with it.”

Caine is writing an expanded second edition, due out this fall, that will add 32 pages of new material, including analysis of Amazon’s environmental impact and efforts in Congress to strengthen laws addressing loss-leader pricing and other monopoly abuses the company’s critics accuse it of. His role in this national conversation, which has attracted coverage from The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times and The New Yorker magazine, continues to expand—last April he was elected to the board of directors of the American Booksellers Association, which promotes independent booksellers in the U.S.—and continues to attract praise from his peers. David Enyeart, manager of Next Chapter Booksellers in St. Paul, Minnesota, and a former member of the Midwest Independent Booksellers Association board of directors (which Caine also serves on) calls him “walking, talking, tweeting proof that booksellers in the center of the country are as vital and valuable as those anywhere else. As an advocate for his store and his profession, Danny reminds us all to speak up for what we value.”

Caine says his embrace of a national leadership role in the indie bookstore community is all about seeking strength in numbers. “One easy way to feel defeated is to feel small,” he says. “I think if we’re going to make any progress on these issues, we need to act bigger than we are. To think of yourself as part of a broader community where everybody is facing the same issues and doing the same work to thrive is a good way to not get overwhelmed.”

In Lawrence, Caine is living the values he advocates. In January, he announced a deal to sell ownership stakes to seven Raven employees, who have a combined 70 years of bookselling experience.

“The ultimate goal is longevity and whatever’s best for The Raven,” Caine says. Spreading ownership among a large group of booksellers brings long-term stability to the store, ensuring it can continue the work it’s doing now well into the future. “I spend a lot of time writing about the wrong way to treat workers; the optimist in me, who tries to focus on positive things, naturally thinks about the right way to do it, and that I should be implementing that at The Raven. I certainly think employee ownership is one answer to the labor-rights issues that are coming up more and more these days.”

The future of the battle against e-commerce giants is unclear, but it probably involves “more writing, more fighting and more bookselling,” he says. And how well suited is Danny Caine to carry on that fight?

“I think he’s pretty darn well suited, because he’s got a lot of energy, a lot of passion for it,” Pat Kehde says. “And I assume there are other people in the United States who have the same concerns and energy. I try to tell myself Amazon is just like Sears and Roebuck used to be, and that all things come to an end. The big guys will overreach. They’ll get bored with what they’re doing, and start to take trips to the moon and all that stuff.”

Despite the “feisty feel” that’s part of The Raven past and present, Caine makes it clear that resistance is not a mano a mano battle.

“The Amazon problem is not something that’s going to be solved by individuals canceling their Prime accounts,” he says. “Big corporations would be happy to have people worrying about this at an individual level, because in some ways that’s a distraction when we’re talking about corporate-level misdeeds. This is something the government needs to act on.”

In this David versus Goliath battle, the giant-killer could use a little help.

Paper Plains Literary Festival

The Raven-led celebration of literary Lawrence offers in-person events April 8-9 after going virtual in 2020 and 2021. Headliners are two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Colson Whitehead; National Book Award finalist Sarah Smarsh, c’03, j’03; and young adult writer Angeline Boulley, author of the American Indian Youth Literature Award Honor Book Firekeeper’s Daughter. Free programs will be at Liberty Hall and livestreamed online. Sponsors of the “collaborative, cross-media, diverse and inclusive literary festival celebrating authors and artists from the Plains and beyond” include the Hall Center for the Humanities, The Commons and the Spencer Museum of Art at KU, and the Lawrence Public Library, the Watkins Museum of History and Explore Lawrence. www.paperplains.org.