Critical test

KU researchers developing a new, at-home assay for COVID-19

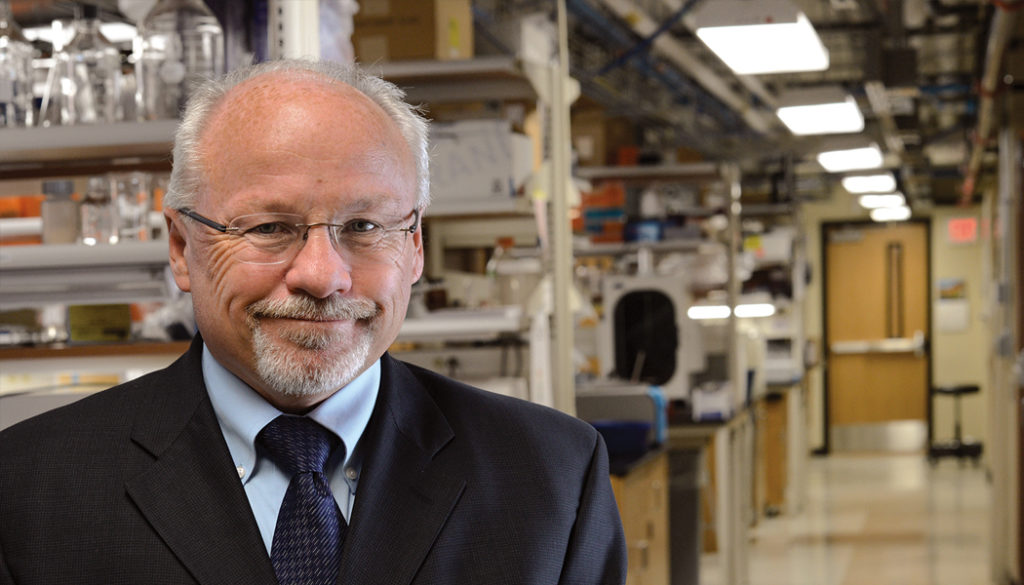

As soon as KU reopened its campus laboratories in June, months after on-campus research was suspended because of COVID-19, Steven Soper and his team of graduate students quickly began work on a test they had conceived remotely in the spring, based on technology KU researchers launched in 2018.

For several years, Soper led a team of scientists in the development of a chip-based blood test that could be programmed to detect a variety of diseases, including breast cancer, prostate cancer and blood-based cancers such as leukemia and multiple myeloma. With the onset of the pandemic, it became clear to Soper that that same technology might be used to diagnose COVID-19 infections.

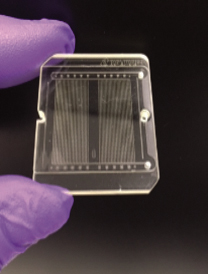

“We repurposed one of the chips we developed for isolating blood biomarkers for cancer diseases in order to isolate SARS-CoV-2 virus particles from saliva,” says Soper, PhD’90, Foundation Distinguished Professor of chemistry and mechanical engineering. “It’s almost the exact same chip.”

The chip in the new test is about the size of half a credit card and includes 1.5 million microscopic pillars; each pillar contains a piece of RNA, or ribonucleic acid, that can detect a protein found on the COVID-19 virus particle. When a contaminated saliva sample is deposited on the chip, those pillars collect the virus particles, which are then exposed to a blue light embedded in the test. The light releases the captured virus particles from the pillars, sending them through an opening just 200 nanometers in diameter, where they can be counted. An electrical signal will alert users if the virus is present. All of these complex components fit conveniently into a single handheld instrument, roughly the size of a cell phone.

“You just apply the saliva sample and it’ll tell you whether you have COVID-19 or not—at home,” Soper explains. “It’s very easy to use, and it takes less than 15 minutes to supply the result.”

The fact that the test can be performed at home, with an accurate result in minutes, imparts a huge advantage over other viral tests currently used to diagnose COVID-19 infections. The commonly used PCR test, while highly accurate, requires submission to a laboratory and results are often not available for several days. Serologic tests, which identify antibodies to COVID-19 in a blood sample, detect only past infection. The test developed at KU not only recognizes active infection but also the extent of a person’s viral load, key factors in determining whether an individual is at risk of exposing others.

Thanks to funding provided by the National Institutes of Health, Soper and his team of about a dozen graduate students in bioengineering and chemistry are currently completing the final stages of validation for the test and will work closely with KU Medical Center in December to conduct clinical trials.

“I think it’s crazy, just seeing how quickly it’s gone,” says Katie Childers, a Self Graduate Fellow and doctoral student in bioengineering, who has been working on this project since March. “Complete props to all of my fellow colleagues and lab mates. They have been in the lab day in and day out for hours over the summer and throughout this whole fall semester. Seeing how quickly it’s coming together is shocking, but looking back at how much time and effort and passion has been put into the project, it’s not as surprising. Just knowing how long research generally takes, it’s really been impressive to be a part of this and to see the outcome.”

As with the blood-based chip test KU launched a few years ago, Soper plans to market the new test through BioFluidica, a San Diego-based company that has an advanced research lab in Lawrence, pending emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration.

“With that in place, we might be able to get this out in late first quarter of 2021,” he says.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Biofluidica is based in San Francisco, rather than San Diego. We regret the error.

RELATED ARTICLES

/