Beat of a different drum: Brandon Sanders makes midlife musical debut

Issue 4, 2023

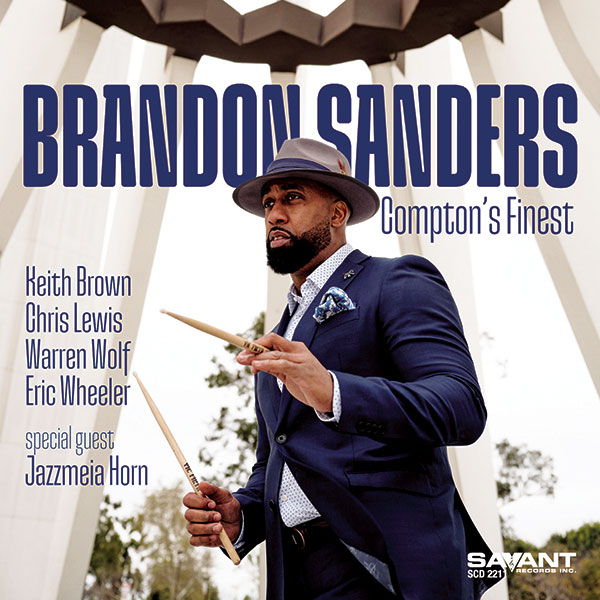

The opening bars of “Compton’s Finest,” the debut album from Kansas City-born jazz musician Brandon Sanders, sends a message borne on a triumphant drumbeat its creator calls Latinesque.

The rhythm is syncopated, the tempo snappy. A cymbal bell rings steady as rain, punctuated by a clap of the snare rim and a thunder roll on the small and floor toms. For 10 seconds Sanders’ beat stands alone, before his bandmates on tenor sax, piano, bass and vibraphone jump in for a swinging take on the jazz classic “Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise.” The intro is an eight-bar mission statement, a declaration of intent in 4/4 time: This is a drummer’s record.

“That rhythm is letting you know, ‘OK, here comes something,’” says Sanders, c’94, g’98, who at 52 has released his first recording after spending three decades learning to play the drums, which he picked up at the relatively late age of 25. “You’re letting people know that you’re a drummer,” he says, “without taking a crazy solo.”

Released by Savant Records on Aug. 25, “Compton’s Finest” presents two original tunes (the blues-inflected title cut and the hard bop “SJB”) and six covers, including jazz standards “Body and Soul,” “Monk’s Dream” and “In a Sentimental Mood,” along with “I Can’t Help It,” a pop tune written by Stevie Wonder and popularized by Michael Jackson. Produced by jazz drummer Willie Jones III and featuring Grammy-nominated vocalist Jazzmeia Horn on two numbers, the record is steadily gaining airplay on radio stations and streaming platforms. On Oct. 9, “Compton’s Finest” broke into JazzWeek’s top 50 at No. 14. By Oct. 30, the recording reached No. 1 and had been streamed on Spotify 684,000 times.

Music has always been part of Sanders’ life, seemingly embedded in his family DNA: His mother, father and stepfather all played instruments, and a great-aunt was an opera singer. But the path to his long-awaited debut, a journey that ran through Los Angeles, Boston and his current home base of New York City, has been marked by many twists and turns—perhaps none as fateful as the one that brought him back to Kansas and KU in the early 1990s.

Sanders spent his early childhood in Kansas City, where his grandmother, Ernestine Parker, owned a jazz club on the Kansas side called Casablanca. When he was 22 months old, he and his mother moved to Los Angeles, eventually settling in Compton, where he attended high school during the late 1980s, a time of intense gang violence. Even for a young man who wasn’t in a gang, just walking the streets could be a harrowing experience.

“I’ve been shot at twice,” Sanders says. “Not because I was looking for trouble, but trying to get to school as a kid. So I can talk about the negatives of Compton.

“But I can also talk about people like Mr. Broadus, who was a choir director; or Mr. Anderson, who was my math teacher and basketball coach. These are people in the community who said, ‘Hey, get your life together. Go to class. Tie your shoes. Make sure that you look a person in the eye. Be a gentleman. Speak clearly.’ Compton was a community of Black people doing positive things during that time—despite what you hear about.”

These role models and mentors inspired Sanders to write the song “Compton’s Finest” and make it the title of his album.

One of the most important positive people in Sanders’ life was a social worker named Mrs. Jones, who worked at the Boys & Girls Club, where he escaped the streets to play basketball and participate in gang prevention and job readiness programs. Interview prep, college essays and how to knot a necktie are among the lessons he recalls. “I always said that if I got to college, I would want to do the same thing that she did,” Sanders says.

A stint at Mt. San Antonio College, where he played for the basketball team, didn’t take. “I was still trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life,” he recalls. “Even though I was in school, I wasn’t really in school, you know what I mean? I was hanging out with the wrong crowd. And those guys, that crowd, could have been destructive to my life if I would’ve continued.”

Throughout childhood, he had returned to Kansas City to spend summers with his grandmother. Sensing his drift at 19, she urged him to move back to attend college.

“She said, ‘I already spent two hours in the admissions line filling out all the paperwork for you to come to KU. But I’m telling you, if you come, you’ve got to set your priorities straight.’

“And I’m thinking to myself, ‘I don’t want to go to Kansas. It’s boring there,’” Sanders says, laughing. “And she said, ‘Maybe you could try out for Kansas basketball.’”

He did come and he did try out, earning a spot on the Jayhawks’ practice squad. That experience—along with a class on jazz he took his first year on the Hill—helped ease what was turning out to be a tough transition for a young man used to bright lights, big city.

Sanders’ mother studied classical violin in high school, and his biological father was a trumpet player. His stepfather, a Vietnam veteran, played trombone in the Army and collected jazz albums. Thanks to him and Sanders’ grandmother (who shared with young Brandon records, photographs and stories of Jimmy Smith, Grant Green, Lou Donaldson and other musicians who’d played at her club), jazz was the soundtrack of his youth. But his understanding of the genre got a major boost when he signed up for a history of jazz class taught by KU professor and renowned music expert Dick Wright.

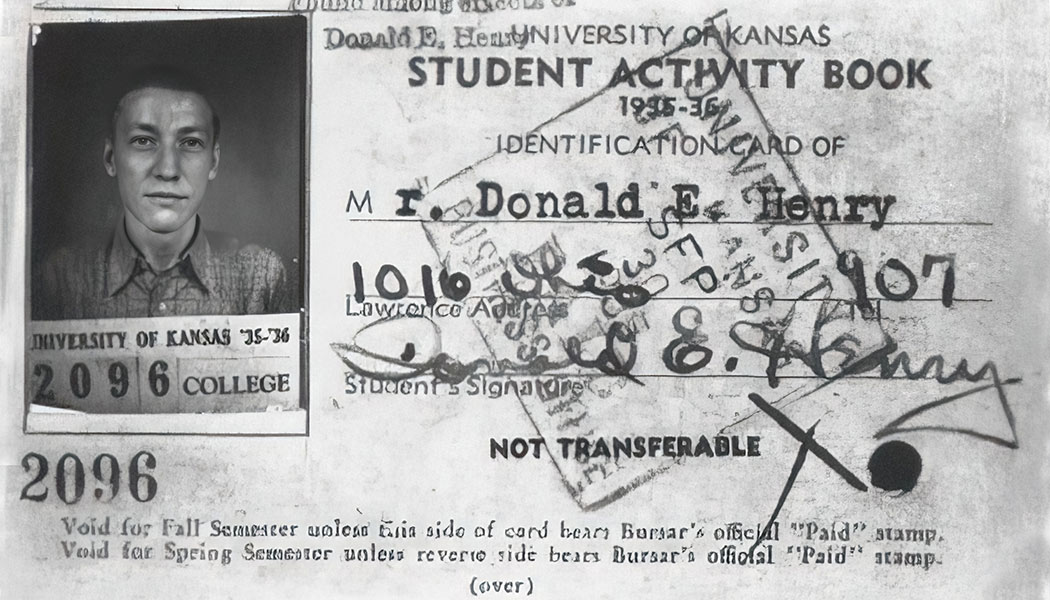

Wright, f’53, g’56, was host of the long-running KANU radio show “The Jazz Scene” and curator of the KU jazz archives, eventually donating some 20,000 records from his personal collection to a trove now considered one of the most complete of its kind in the Midwest. His Murphy Hall office stuffed with records and a pair of turntables exerted a powerful tug on Sanders.

“I was so fascinated with Mr. Wright’s record collection that I would sleep on the floor outside his office in the morning to be the first one in when he started office hours at 8:30,” he recalls. “You know how students sleep in Allen Field House before a game? That was me waiting for Mr. Wright.”

They formed a friendship that lasted until Wright died in 1999. Sanders took every class Wright taught and a few more they invented; he spent hours pulling records from shelves, spurring long talks the student often extended by walking the professor across campus to his next class or appointment. He drove Wright and his wife, Maxine, to Kansas City when Wright interviewed visiting musicians onstage as part of the Folly Theater Jazz Series. And Wright made cassettes and CDs for Sanders that helped deepen his acolyte’s appreciation for the music.

“My stepfather gave me a taste, but Mr. Wright got me into studying and listening to records every day,” Sanders says. “When I came home to LA, (my stepfather) was surprised, because now I was educating him on jazz. I was listening to heavy stuff like Eric Dolphy and Charlie Mingus and Lee Morgan and Dexter Gordon. He’s like, ‘Wow, where did you hear all this?’ And I’d tease him: ‘Man, you got to get hip to Dick Wright!’”

Coming to Kansas was a rebirth (“My story is about resurrecting my life,” Sanders says) and a reset. He earned a bachelor’s in communications and a master’s in the School of Social Welfare. He worked at the Boys & Girls Club in Lawrence and Kansas City, launching a career in social work that continues today at The Masters School in Dobbs Ferry, north of New York City, where he’s a mental health counselor and tennis and basketball coach. And he picked up the drums, starting the long road to mastery that led him to Berklee College of Music in Boston in the early 2000s, a thriving performance career as a leader and sideman in New York City, and the February recording of “Compton’s Finest” at The Bunker Studio in Brooklyn.

Sanders says he plays music because of two people: his grandmother, who bought him his first drum kit and was his biggest fan until her death in 2013, and Dick Wright.

He still grieves for both.

“My life was touched so much by Mr. Wright. If it wasn’t for people like him and my grandmother …” Sanders says, his voice breaking. “The music that he poured into me, it changed my life.”

From the Latinesque drum intro of the first track to the bouncy, vibes-and-sax propelled melody of the final cut, “Compton’s Finest” ticks a box that’s extremely important to the bandleader: It swings. “I like jazz that’s swinging,” Sanders says. “My grandmother always told me that is the main goal of a jazz band, to swing. That you know you’ve got a good band when people are dancing instead of sitting.”

“Brandon has a great feel, the way he swings,” says producer Willie Jones III. Experienced at leading a band from behind a kit, Jones says it’s not about how many solos you take—an approach Sanders, who calls himself a “humble” musician, agrees with. “He doesn’t have preconceived notions about how much he should solo,” Jones notes. “He just swings, just plays the music. And if you do that, people want to play with you. It speaks volumes that the musicians on his record were like, ‘Yeah, we would love to record with you.’ Because they love the way he makes the music feel.”

Echoing his professional role as a social worker, Sanders also brings to his music a desire to inspire. “It’s about trying to lift people’s spirits,” he says of his goal as a musician. “It’s the same thing I try to do as a social worker. It’s about making sure that people leave feeling different than when they came in.”

The lively final cut—jazz great Lewis Nash in his liner notes praises it as “feel good music … with a danceable groove”—Sanders wrote for a friend who inspired him to persevere through hard times. Much like the title track, a minor blues that acknowledges the stress he experienced running a gauntlet of rival gang territories as a kid, “SJB” celebrates resilience.

Resilience is essential to making it as a jazz musician, especially following the “definitely unusual” route Sanders took.

“To start playing drums at 25 and be where he is now?” Jones says. “And I don’t mean he started playing in high school, then got serious when he was 25. He literally started from square one. And oh, by the way, he’s a counselor; he’s working a 9-to-5 and raising a family. But he loves music so much that from the time he was 25, he’s been working to better himself, developing himself as a drummer. He collects all the records, listens all the time, goes to gigs checking out all the different drummers. So, yeah, at 52, to make his debut record, it’s nothing short of incredible. And now he’s working; he’s getting gigs. He’s making up for lost time.”

Sanders’ mother told him that his grandmother would be “tickled pink” to know he had a jazz album to his name. He’d like to think Dick Wright would be, too.

“They got me into this,” he says. “When I came to Kansas City, I didn’t know what I was going to do. My grandmother paved the way, and I met people like Mr. Wright, and he introduced the music.”

Teaching a class on mindfulness at The Masters School, Sanders played a recording of the Kenny Barron composition “Voyage.” Only after the lesson was done did he reveal the recording was from “Compton’s Finest.” Now with students (and a massive record collection) of his own, he’s passing along something he learned long ago, something he reaffirms each time he picks up his sticks and prepares to “leave the shoreline,” as James Baldwin wrote of the jazz improviser’s imperative, “and strike out for the deep water.”

“I believe music is a healing force,” Sanders says. “I believe music is a beautiful thing, because it changed my life.”

“Compton’s Finest”

Savant Records, $17

Brandon Sanders—drums

Chris Lewis—tenor saxophone

Keith Brown—piano

Warren Wolf—vibraphone

Eric Wheeler—bass

Jazzmeia Horn—vocals

Steven Hill is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Portraits by Eva Kapanadze

Illustrations by Chris Millspaugh

/