‘Ancient Apocalypse’ and the consequence of conspiracy

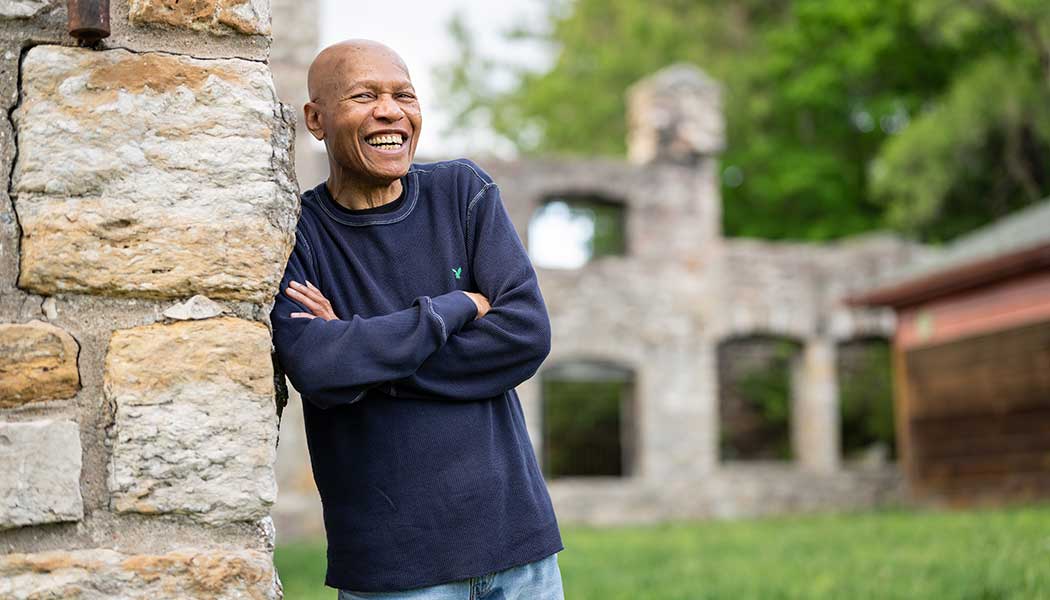

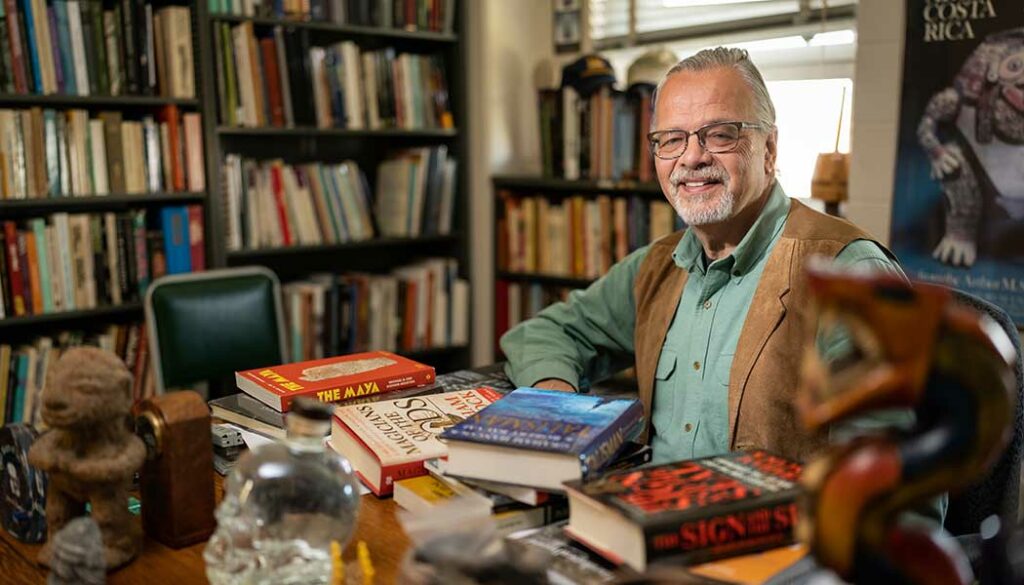

When Professor John Hoopes arrived at KU in fall 1989, one of his first projects was to establish a critical-thinking course similar to one he had helped launch earlier in the decade as a Harvard graduate student. Hoopes has taught “Archaeological Myths and Realities” ever since, initially as a 400-level course designed for anthropology majors, and currently as a 200-level course open to all students seeking to fulfill a KU core requirement for critical thinking.

Three-plus decades later, the course is more relevant than ever.

While teaching his students foundations of critical thinking, especially as applied to the complex worlds of scientific research and outreach, Hoopes is also engaged in a public quest to thwart what he sees as a particularly dangerous example of pseudoscience: the Netflix hit series “Ancient Apocalypse.”

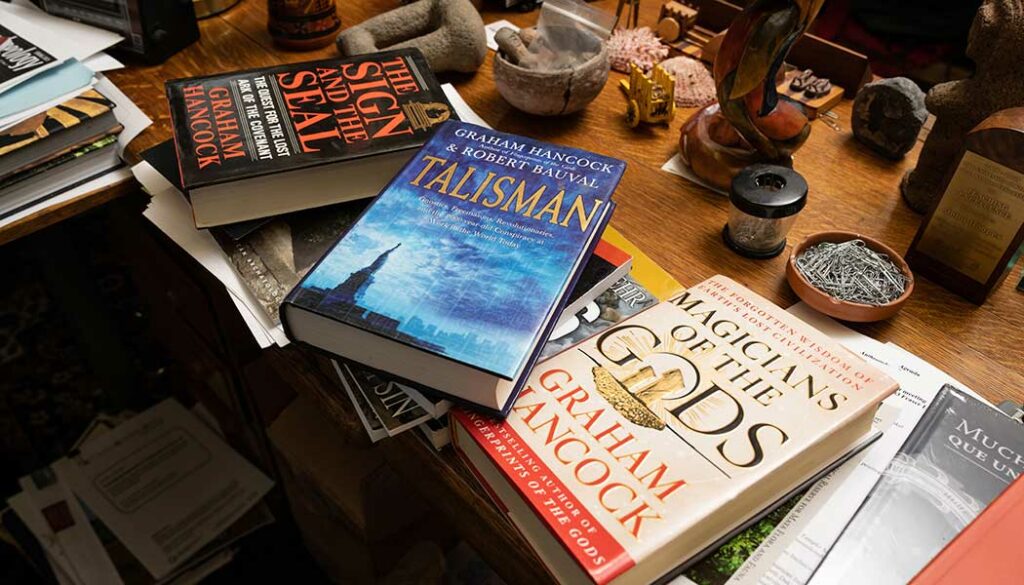

The show’s creator and host, prolific British author Graham Hancock, has been on Hoopes’ radar since Hancock’s 1990s appearances on the late-night conspiracy outpost “Coast to Coast AM” with Art Bell and George Noory. Influential podcaster Joe Rogan has shared his platform with Hancock 20 times since 2013, and, thanks in part to that exposure, Hancock’s “Ancient Apocalypse” became one of the top 10 Netflix shows in 31 countries shortly after its November 2022 launch.

“Hancock should be studied by journalists, because he is such a master manipulator,” Hoopes says, explaining exactly how his coursework applies to real-world scenarios. “If you want to understand how to produce effective propaganda, watching how he does it is very instructive. He makes a systematic use of logical fallacies. He knows which ones most people are not going to be able to recognize, whether it’s cherry picking, or whether it’s setting up a straw man, or whether it’s making a bold statement or hasty generalization. All of these are techniques that he uses.”

To introduce his students to the concepts of critical and clear thinking in the sciences, Hoopes first turns to a deep read of Carl Sagan’s classic The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, which includes Sagan recalling an encounter with an intelligent, well-read taxi driver who had an interest in, but no understanding of, Sagan’s work in astronomy: “All over the world,” Sagan wrote, “there are enormous numbers of smart, even gifted, people who harbor a passion for science. But that passion is unrequited.”

Education was failing its mission of teaching science and critical thinking, Sagan argued, enabling “spurious accounts that snare the gullible. … Skeptical treatments are much harder to find. Skepticism does not sell well.”

And that, Hoopes says, is “the linchpin of what we’re talking about here.”

Hoopes grew up in Baltimore with a typical boyhood interest in fantastic stories of ancient alien astronauts, the Bermuda Triangle, healing powers of pyramids and crystals. He even wrote a 10th grade research paper on the “lost continent of Atlantis,” and acknowledges that his passion for archaeology was spurred, at least in part, by his “interest in some of these alternative theories.”

But fanciful tales carried along on dreamy currents that defined the Age of Aquarius long ago outlived their innocent emergence; what once was playful has since grown the whiskers of unsightly aging.

“It was in 1973 when I went to see the film ‘Chariots of the Gods’ in a movie theatre,” Hoopes says. “That was 50 years ago. Here we are 50 years later and this stuff is bigger than it ever was. It didn’t go away, and I think it’s having pernicious effects.”

Hoopes majored in archaeology at Yale College. He spent six months after graduating on archaeological projects in Ecuador—his specialty is the archaeology of southern Central America and northern South America—and he worked as a professional archaeologist at varied sites that included subway construction in Washington, D.C., and pipeline easements for oil and gas projects in the New Mexico desert.

Although he earned only $250 a week, Hoopes “lived on a shoestring” to save half of every paycheck, and in summer 1982 he was hired to assist Harvard archaeologist Stephen Williams in developing the course “Fantastic Archaeology.” Williams’ idea was to use popular pseudoscience topics such as the Great Pyramid of Giza, Easter Island, lost continents, ancient astronauts and Stonehenge—the same stuff that had thrilled Hoopes’ reading as a boy—to teach his students skills in critical thinking, while at the same time conducting his own research into the backgrounds of those who accumulated wealth by peddling lies.

Williams even clashed academic swords with a Harvard colleague, a professor of comparative zoology, who had fallen under the spell of what he thought to be stone inscriptions carved across North America by mysterious travelers from the mists of time who had somehow crossed the Atlantic Ocean; another Harvard colleague was selling popular books on similar tales of an unknown ancient America.

Hoopes continued developing the course as a graduate assistant while working toward his doctorate, and he found inspiration in his mentor’s dedication to teaching young scholars how to think.

“I think he understood that the authors were challenging authority, and, back then, that was a very appealing thing,” Hoopes recalls. “He saw how some very weird stuff resonated with the general public, and he found it insane that these books that were based on fantasy were getting so much attention.”

Hoopes believes the mission of his critical-thinking course is vital to a college curriculum, and he argues that it should be an academic staple for students in elementary and secondary schools. Sadly, that is not—and never has been—an easy sell.

“The problem is that in a capitalistic, consumer-based society, the powers that be benefit from having a population that is not good at critical thinking,” Hoopes says. “The same kinds of logical fallacies that you see in Graham Hancock’s series are ones used in the commercials that you watch on a regular basis, and these deceptive advertising methods are something that the economy sort of depends on.”

As hucksters spin their tales for consumers who lack the skills to resist such deft salesmanship, a strange contradiction takes root: A belief in the unbelievable somehow fosters distrust of the provable. Conspiracies, Hoopes contends, are both real and dangerous, and their existence is why pseudoscience that has far broader exposure than authentic science needs to be called out, exposed and ridiculed.

Hoopes has dutifully done just that, especially since the sudden rise of predictions for a 2012 apocalypse based on absurd readings of Maya calendars (“The Gloom of Doom,” issue No. 4, 2010). Pop-culture conspiracy theories—whether a Maya death knell, the lost civilization trumpeted on “Ancient Apocalypse,” or JFK assassination tropes still championed by educated Americans who otherwise proclaim themselves immune from such maddening hysteria—have real-world consequences.

“They absolutely do,” Hoopes says, “and it’s all a distraction from real conspiracies to keep knowledge from the American public.”

Hidden within the chaos of the fanciful, there are also ominous conspiracies to “hide the truth of the treatment of Native Americans in American history,” including the Indian Removal Act, forced migration on the Trail of Tears, dishonored treaties, stolen lands. Hoopes also mourns an “active conspiracy to remove Black history from the American curriculum by labeling it ‘critical race theory,’ when that’s not what it is,” while “claiming that’s not something that should be taught because it makes white students feel bad about their own heritage.”

There’s also the ongoing conspiracy, as Hoopes sees it, “not to tell the truth about the reality of LGBT people who’ve existed for millennia in every culture on the planet, and that there have been trans people throughout history, and gender is a spectrum, not a duality. There’s a struggle to tell that story, as well, because there’s a conspiracy to hide it.”

When audiences tune in by the millions to watch television shows such as “Ancient Apocalypse,” which purports to link global advancements made within the past millennia or two to what Hancock describes as a far older “civilization that was lost in the great cataclysms of flood and fire that we know occurred near the end of the last Ice Age,” they can find themselves enamored of, and comfortable with, the notion that scientists, experts, are hiding the real truth.

Hoopes, whom Hancock has called “the most vehement and insulting of all archaeologists,” terms it the “cultic milieu of conspiracy theory,” which, once embraced, opens the door to such real-world dangers as vaccination conspiracies and climate change and election denial.

“All of those things,” Hoopes says,“go together.”

Shortly after “Ancient Apocalypse” made its Nov. 11, 2022, debut, it shot to the top of Netflix’s rankings, which helps explain the swift reaction against it. On Nov. 23, the prominent U.K. newspaper The Guardian bemoaned “the danger of a show” that “whispers to the conspiracy theorist in all of us,” while also slyly noting that the senior manager of unscripted originals at Netflix “happens to be Hancock’s son. Honestly, what are the chances?”

The Society for American Archaeology on Nov. 30 published an open letter (which Hoopes helped edit) to both Netflix and ITN, the eight-part show’s production company, denouncing the “docuseries” label as unwarranted for a program “based on false claims.” The letter also cited Hancock’s “willfully seeking to cause harm” to serious archaeologists with aggressive rhetoric, and, most damning, called out the show’s foundational theory for its “long-standing association with racist, white supremacist ideologies” that “does injustice to Indigenous peoples and emboldens extremists.”

“Contrary to Hancock’s claims, archaeology does not willfully ignore credible evidence nor does it seek to suppress it in a conspiratorial fashion,” the letter continues. “The assertions Hancock makes have a history of promoting dangerous racist thinking. His claim for an advanced, global civilization that existed during the Ice Age and was destroyed by comets is not new. This theory has been presented, debated, and refuted for at least 140 years. [The theory] steals credit for Indigenous accomplishments from Indigenous peoples and reinforces white supremacy. …

Hancock’s narrative emboldens extreme voices that misrepresent archaeological knowledge in order to spread false historical narratives that are overtly misogynistic, chauvinistic, racist, and anti-Semitic.”

Also within days of the series’ debut, The Conversation, a popular-audience online academic journal, proclaimed that “Netflix’s enormously popular new show … is an all-out attack on archaeologists.” The article’s author, Flint Dibble, research fellow at Cardiff University, wrote, “This sort of ‘race science’ is outdated and long since debunked, especially given the strong links between Atlantis and Aryans proposed by several Nazi ‘archaeologists.’ These are the reasons why archaeologists will continue to respond to Hancock. It isn’t that we ‘hate him’ as he claims, it is simply that we strongly believe he is wrong.”

Also joining the argument from the outset was Hoopes, who almost daily used his active Twitter platform to denounce Hancock. “Hancock’s series on Netflix was not to debate archaeologists, but to use or dismiss them as he saw fit,” Hoopes wrote Jan. 5. “He also features various non-archaeologists and pseudoarchaeologists talking about archaeological phenomena. It’s a mess.”

Hancock on Jan. 30 responded with a 16-page letter posted to his enormously popular blog, in which he states that “Ancient Apocalypse” continues the mission of his earlier books “to honour indigenous voices and perspectives in ways that the SAA, despite much virtue-signalling,does not.”

Hancock’s protests did nothing to slow worldwide archaeologists’ unified surge against “Ancient Apocalypse,” which the community of scholars had identified as a particular danger to their science because of the show’s global popularity, reaching audiences lacking in both academic resources and critical-thinking skills that would allow them to see the “docuseries” for what it really is, at least in Hoopes’ estimation: “speculative nonfiction.”

Hoopes is careful to note that his zeal for critical-thinking skills and his passionate dislike for “Ancient Apocalypse” should not be mistaken for a lack of interest in fantastic archaeology-based or science-adjacent stories of adventure and intrigue.

“There’s a very important place for speculative fiction,” Hoopes says, citing

as examples Jean Auel’s wildly popular 1980 novel, The Clan of the Cave Bear,

and J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, both clearly labeled as fiction.

Precisely in step with the emergence of the internet, with its immense power to generate enthusiasm for deliberate falsehoods, a pair of Charlton Heston-narrated specials—“The Mystery of the Sphinx,” in 1993, and 1996’s “The Mysterious Origins of Man”—proved big hits for network TV. The specials established a template for purveyors of pseudoscience to sidestep identifying their works as fiction.

But if such conspiracy-theory fueled TV filler can continually grab our collective attention, why can’t the real stuff sell, too? Why aren’t we enraptured by true tales about our ancient forebears and their very real human adventures, their loves and lives and foibles and fearlessness?

The problem, as Hoopes sees it, is that scientists “are very humble, in terms of what archaeology can tell us. And there are all kinds of parts of these stories that people want to know that we just don’t have the answers for.” Where Hancock would deftly insert a dramatic but what if …, actual scientists sharing the truth as they know it would instead be compelled to end the narrative. The “but what if” should happen in laboratories and on field expeditions, not popular TV shows.

“Archaeologists are reluctant to go beyond what the data says,” Hoopes says. “We can speculate ourselves, but we’re hesitant in saying things that we know will probably change, that we know new data will alter. That may be one of the reasons why we tend to not go there, and at the same time, that’s the big hook for people watching these shows: It could be this; it could be this other thing.

“We as archaeologists need to be better about inviting the general public into that level of adventure, and imagination, and creativity, about possible answers to things in the past. And then say, ‘Well, how could we answer this? What information do we need to know this? How can we find that information? How can we use technology? How can we use a new approach to be able to recover these things that we’d really like to know that we don’t know yet?’”

Theories about humanity’s ancient past need not be conspiracies. In the right hands, they never were.

Editor’s note: Professor John Hoopes and two international colleagues recently co-authored a thorough examination of pseudoarchaeology’s long history and caustic influence: Apocalypse Not: Archaeologists Respond to Pseudoarchaeology, published in the May issue of The SAA Archaeological Record.

Chris Lazzarino is associate editor of Kansas Alumni magazine.

Photos by Steve Puppe

/