‘Always on the edge’

Former CIA officer illuminates yet more corners of the shadow world

Once was a time when Bob Wallace lived within the shadows of the secret service, forging a long career as a CIA operations officer, including three tours as a chief of station. Even when he capped his career at the CIA as director of the vaunted Office of Technical Service, Wallace continued his work behind the scenes, unknown to all but his closest colleagues.

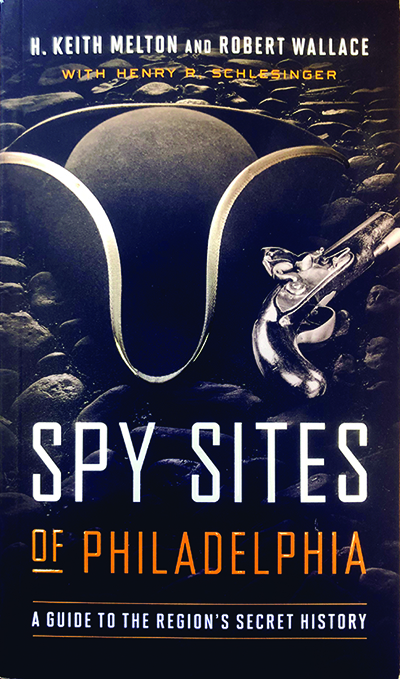

Wallace, g’68, shed his invisibility cloak when he co-wrote Spycraft [issue No. 4, 2008], the authoritative history of the CIA’s super-secret spy techs and their brilliant inventions and espionage adventures, his first public partnership with the internationally recognized intelligence historian H. Keith Melton. The latest of five Wallace-Melton book collaborations is Spy Sites of Philadelphia, which follows earlier histories of espionage from the Revolutionary War to the Cold War and beyond in New York City and Washington, D.C.

Wallace and Melton are also co-executive producers of the eight-episode Netflix docuseries “Spycraft,” based loosely on their book, for which they also appeared as expert commentators and helped filmmakers find former espionage officers who were free to speak on camera.

Spy Sites of Philadelphia By H. Keith Melton and Robert Wallace Georgetown University Press, $24.95

“Since the Second World War, we have had this established intelligence apparatus, the intelligence community, the well-organized agencies, and I think that presents a false picture of what the history of American intelligence is really like,” Wallace says of the appreciation he’s gained for the history of global espionage since leaving the CIA. “Beginning with the Revolutionary War, through the Civil War, World War I, and even through much of World War II, a lot of the best intelligence work was done by people I would call ‘citizen spies.’ There was not a professional intelligence service. There wasn’t an organization that trained people to be intelligence officers or spies. These individuals just kind of came to it on their own, and they made do.”

As with the previous installments of the Spy Sites series—all gorgeously illustrated, thoroughly researched and presented with hundreds of short entries illuminating people and places otherwise forgotten or even unknown to history—Wallace and Melton’s latest book tells stories that originate in and around one locale, yet serve the larger sweep of American history.

As they demonstrate throughout the Spy Sites books, the national destiny turned time and again on unlikely heroes risking their lives in unexpected adventures.

“You can’t tell who the spy is,” Wallace says. “They could come from any walk of life. The spy really can be the person next door. Spy operations occur wherever the spy can conduct the operation, not where you think it might be. Spies aren’t met just in dark corners and back rooms of bars. They’re out there in plain sight and you never see them.”

After earning his master’s degree in political science, Wallace enlisted in the Army and served harrowing tours as a Ranger in Vietnam; he was a Congressional aide when the CIA finally took notice of the application he’d submitted before leaving KU. More than 25 years later, Spycraft required years to pass muster at the CIA’s publication review board, yet the agency eventually signaled its enthusiastic, hard-won support by approving a foreword by former director George Tenet.

Wallace hesitates to agree that intelligence work can, at times, be characterized as fun, instead describing it as an “adrenaline-producing” career path, a keystone to America’s founding and ongoing existence.

“Whenever the nation was facing a crisis, intelligence was a vital element in resolving it, to the good or the bad. If we got it resolved well, intelligence played a critical role. If it didn’t get solved well, or addressed well, intelligence probably didn’t do its job well,” Wallace says. “The fun side of it is kind of parallel to the idea that spies all believe that what we are doing is important. There’s a high level of satisfaction in doing it well.

“You’re a race car driver, in a sense. You’re right on the edge, always on the edge. You’re trying to push it to the maximum. You also know that if you go over the maximum, you wreck the car and you kill yourself. When you go over, an intelligence failure frequently has severe consequences. It’s not a mistake that can be erased.”

RELATED ARTICLES

/