A Man Walks Into a Bar

The day he turned 28, Sean Powers made a promise to himself. Three actually.

He would quit drinking, maybe for a year, maybe forever. He would hike the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2,654-mile beast of a wilderness challenge that snakes through California, Oregon and Washington in some of the highest mountains of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada ranges. And he would try his hand (finally!) at stand-up comedy.

All at the same time.

Forsaking booze while trekking through remote areas where resupply opportunities are intermittent and physical challenges constant, where sheer drops and ice chutes and avalanches are real possibilities instead of action movie boilerplate, where trailside liquor stores with hike-through windows number exactly zero—yeah, that makes sense.

But stand-up?

Schlepping a heavy pack on blistered feet for months through wind, rain and the occasional high-altitude snowstorm might not strike you as a mother lode of pure comedy gold, but for a young adult deep in the throes of a quarter-life crisis who’d already embraced risk-taking as a viable life strategy, the unconventional pairing looked like an elegant solution to a dilemma.

Powers, j’14, worked in advertising sales at the University Daily Kansan all four years on the Hill, rising to become the student paper’s director of sales as a junior and business manager as a senior. After graduation he landed a job as account executive at a major-market TV news station, Denver’s ABC affiliate Channel 7. Within a year, he’d chucked the promising career and moved to Guatemala to teach economics and history to high school students.

The reason?

“Love,” Powers explains. “I met a girl at KU.”

They lived together in Denver until she took a teaching job in Central America, and when he helped her move and learned more about international teaching, it appealed to him.

“I got this feeling in my stomach that I got when I first heard about KU, when I first heard about the journalism school, about the Kansan. And the same feeling I got when I heard about international teaching is the same one I got with the Pacific Crest Trail and comedy.”

That feeling, Powers says, is the first thrilling spark of an adventure blazing into being.

“It’s your gut telling you, ‘Hey, this is scary. This is going to be a long road. This is going to be a risk,’ but a bigger part of you overrides the risk and says, ‘Yes, but it will be fun doing it.’”

He taught for three years in Guatemala before taking a teaching gig at a middle school in Colombia. He was there when COVID-19 prompted a strict lockdown that turned Bogotá into a ghost town.

“It was devastating because the kids are just demoralized; they’re sitting in their rooms, separated from friends,” Powers recalls. “And I wasn’t able to give them the answers, to say it’s going to be OK.”

To inject some fun into their online classes, he began making playful lesson intros that tapped a love of comedy dating to his own childhood, when he’d come home from elementary school every day and—unbeknownst to his parents—watch Comedy Central.

His students loved it, and the work reawakened his ardor for setups and punchlines and making people laugh.

“I put all this effort into making an entertaining experience just to be part of some seventh-grader’s afternoon,” Powers says. “I was like, I could put this energy into building my own brand as a comedian. Why not do that?”

COVID eventually forced him to leave Colombia. He lined up a teaching job in Bangladesh, but employers were slow to resolve transportation, health care, pay and safety issues. With Plan A looking shaky, he focused more closely on his perennial Plan Bs: He’d long wanted to hike the Pacific Crest Trail; he’d long wanted to see if he had what it takes to tell jokes onstage in front of strangers.

Trouble was, the pandemic had shut down both the trail and stand-up comedy. In October 2020 the Pacific Crest Trail Association postponed a decision on releasing hiking permits for the coming year. Comedy clubs in Powers’ hometown, Minneapolis, Minnesota, were dark. Therein lay the dilemma: The very crisis that had inspired him to act was making it impossible to do so. What was a wannabe thru-hiker/joke-cracker to do?

“I came up with an idea: If I get the permit for the PCT, why don’t I just walk and work towards a show? Why don’t I just write all my material from day one on the trail and try to have a show by the end?”

He began studying a book by Stephen Rosenfield of the American Comedy Institute (ACI), “probably the best-known comedy teacher in the country” according to The New York Times. Soon he reached out to Rosenfield with a question: If I come to New York, will you teach me?

“He said, ‘You don’t have to come to New York; we’re on Zoom.’”

Powers took Rosenfield’s online class and discovered a world of stand-up Zoom rooms where aspiring comedians try out new material—for one another, as a rule, rather than for appreciative audiences primed by a club’s two-drink minimum.

“Usually it’s four or five other comics waiting to perform, not really listening to you,” Powers says. “It’s a terrible, terrible environment, but it teaches you cadence. You get better. And if you can make them laugh, chances are your stuff is actually funny.”

A lively online gathering in Bellingham, Washington, the Ember Open Mic, was a welcome exception—a spirited, fun mix of comedians and fans that felt more like comedy heaven than Zoom purgatory.

“They had music and they’d get 30, 40 audience members who were interested, engaged. It felt like performing.” He showed up every Saturday night, and after several weeks he pitched an idea.

“I said, ‘Look, I want to hike the Pacific Crest Trail. Has anyone heard of that?’” Powers recalls. “Most of them hadn’t.”

He explained that the trail spans the United States from Mexico to Canada and near its northern terminus passes within a few dozen miles of Bellingham. He’d make the hike, writing material as he went and trying it out in pop-up shows along the way, then headline a performance in Bellingham at trail’s end. Not only did the idea give him a framework for generating a show, it gave him a hook for promoting it. “I said, ‘Why don’t I walk to my first show?’”

By spring 2021 Powers had hiking permits in hand, resupply boxes packed and ready to mail ahead to towns along the trail, and more new gear (he’d joke onstage later) than an REI mannequin.

He set out April 17 on a journey that would take 136 days to complete, with

as many emotional ups and downs as the desert-to-mountain course he traversed. One moment he was plunging down an ice chute in terror; another he was waiting in line at a small-town post office to pick up a box packed with custom toilet paper and stage props.

“It was,” Powers says of the epic trek, “a lot like comedy. You fall flat, but you have to keep going.”

The Walk of Shame had begun.

You gotta get a gimmick if you want to get ahead. So goes the old show-business saw.

As gimmicks go, building one’s comedic chops by hiking 2,654 miles while writing jokes and testing them on fellow hikers along the trail turns out to be a pretty original one.

“I’ve never heard anything like it,” says Nathan Romano, organizer of Ember Open Mic and co-founder—with his wife, Cecilee Romano—of Bellingham Entertainment, a comedy production company. They agreed to help Powers promote two Bellingham shows.

“I was definitely intrigued,” Romano says. “I will say I didn’t know how realistic it was, in terms of actually happening, but I believed in it 100%.”

Headlining a show so early in one’s stand-up career “is unheard of, as far as drawing a crowd that’s big enough and then having the confidence to stand in front of a hundred people and perform something you came up with,” according to Romano. “There’s people I started doing stand-up with 11 years ago, and none of us have headlined our own show.”

There were many ways the whole venture could go south. Wildfires or other acts of nature could shut down the trail. COVID restrictions could shut down Bellingham. And there was the small detail of the miles Powers had to cover: Nearly 3,000 in four months of often dusk-to-dawn hiking.

“It’s hard to relate that to someone who doesn’t thru-hike,” Romano says. “It’s hard to picture that mentally. Looking at a map, it looks small: There’s Mexico, there’s Canada. But using your two feet to walk it? I don’t know if there’s a way to impart that distance to people. It’s huge.”

Thru-hiking, as the end-to-end backpacking of long trails like the Pacific Crest, Continental Divide and Appalachian is called, has its own culture, and one of its quirks is the bestowing of trail names on hikers. A couple of weeks into the trip, Powers already had acquired his.

Trail names are often based on a physical characteristic or an embarrassing story, and they must be given by another hiker, not self-selected, although you can refuse a proposed name. “So trail names are like bullying,” Powers quips, “but you get to choose how.” His trail name—a mispronunciation of his first name—was Shame. He embraced it.

“Everyone wants a fun trail name,” he says. “Sunshine. Skittles. Butterfingers. Twinkletoes. Yogi Bear. Shame! It’s very different. I grew up Irish Catholic in the Midwest. I am Shame!” Best of all, it made people laugh. One day during a trail performance, he had an idea: “I’ll call my comedy show ‘The Walk of Shame.’”

For the first thousand miles he put on trail shows almost daily. Hikers tend to gather in communal campsites by night, and using an oversize inflatable mic he’d brought as a prop, Powers would stand before PCTers and riff on the absurdities of life on the trail and life in general. He enlisted fellow backpackers to film skits to promote the shows. One introduced an alter ego, Shame LeGüf, a cranky, chain-smoking mime rejected in his native France and forced to walk to the only city that accepts his art, Bellingham. Another posits a world ruled by Bigfoots, who search for an elusive, mythical human who prowls the wilderness.

He started handing out matchbooks emblazoned with his logo, part gift, part marketing piece, until he hit on a better idea.

“People would take matches, but I was like, OK, what is something that everybody really wants? Oh my God, toilet paper! Everyone wants toilet paper. I told my sister this idea. She was like, ‘Hey, your birthday’s coming up. Let me do this for your gift. Let’s put your logo on toilet paper.’ So she shipped it to me and I started giving that to people instead of matches. It’s got my face on it.”

While other hikers are getting care packages stuffed with Mom’s cookies and fresh socks, Powers says, “I’m getting shipped toilet paper, a Bigfoot mask and mime makeup.”

That marketing savvy—a skill developed in his sales roles at the Kansan, Powers points out—would prove valuable.

“The fact that he walked such a great distance … really helped people want to find out more,” Romano says. Bellingham Entertainment’s other shows had drawn pushback from people who felt it unwise to put on events amid a pandemic. “With Sean, people were willing to venture out, local magazines were willing to write about it, and we were able to get sponsors … because this was such a big, unheard of thing he was doing.”

Gimmicks, of course, are designed to draw attention, to heighten interest by playing to our fascination with the novel. For that reason they’re often derided as hollow stunts with little substance beneath the flashy surface. But Powers discovered that writing a stand-up routine while hiking the PCT was no mere contrivance: The comedy affected his trek and the trek affected his comedy.

For the first weeks on the trail, he explains, the adventure is fresh and the months and miles stretching before you seem like a gift. “You’re having so much fun, and every day is incredible. And then after several weeks, after you get out of the high Sierras around mile 1,000, it really starts to hit you that you’re not even halfway through this hike yet. It starts to dawn on you, am I making the right decision? I’ve got three more months to go. Why am I doing this?”

Hiking starts to seem less like a lark and more like a job, “not a 9-to-5 job but a 5:30-in-the-morning-to-7-at-night job,” he says. Strenuous days, when comforts are few, food is scarce, or weather is nasty, take a physical and mental toll.

“Comedy gave me a sense of purpose; the pressure I put on myself to come up with a show helped get me through some pretty hard days, gave me something creative to think about. You’re trying to process not just what’s happening, but how is it relatable? How can I articulate this to other thru-hikers, to people who just like the outdoors, to somebody who doesn’t know what a thru-hike is? And how do I make it funny?”

Such discomfort, angst and suffering aren’t just bearable for comedians, notes Stephen Rosenfield. They’re essential.

“The golden land for a comedian is putting yourself in a struggle, because that’s where the laughs are,” the ACI founder says. “In comedy, you want the short end of the stick.”

Powers possesses something that is the most essential asset for a performer, Rosenfield believes. “It’s what I call joyous communication. Sean has a great time being up there talking to the people sitting out there in front of him. It doesn’t mean you’re happy, because a happy comedian is a contradiction of terms. It means that you are happy to express how mad you are or angry or frustrated about something. You can’t succeed in this business without being capable of expressing that to an audience. And he clearly has it.”

Those sitting in front of him at trail shows could be just a few folks gathered around a campfire, or (as happened one memorable night at a national park after the power failed, leaving Shame the only show in town) dozens of entertainment-starved trekkers.

“It helped me broaden my voice,” he says of the PCT performances, “because I’m not just pitching my comedy to the Midwest or the West Coast. Every night you’re meeting people from a different part of the world, and if you’re open to it, they’ll give you feedback.”

Strangers even sought him out to ask if he had any new jokes to share. Then there was his “trail family,” hikers who moved at the same pace as Powers, and thus saw— and heard—a lot of him day after day.

“After a while, they’re like, ‘Dude, stop with the jokes! We’ll give you extra Power Bars if you’ll just shut up.’ I may be the only comedian ever paid not to perform.”

Sean Powers: The world’s first sit-down comedian.

By late August, with Powers nearing the end of his hike and with shows scheduled for Sept. 23 and 24 in Bellingham, Nathan Romano went out to the PCT to film a promo with him.

“I wanted to meet Sean for the first time while he was still on the trail,” Romano says. “As we were shooting, he kept talking about his next project, and I tried to tell him, ‘Hey, you’re at the tail end of this huge project, maybe just take a moment and sort of sit with the fact that you’ve done this amazing thing. Because to me it seemed like he was so used to walking the 30 or 40 miles each day, with the twist of writing comedy and performing comedy the whole way, that it wasn’t really such a big accomplishment. I tried to remind him that this is not something that a lot of people do.”

Powers, he notes, has a lot of ideas—and a lot of ambition to follow through on them. “He’s definitely an outlier in that regard,” Romano says. “But I guess the other side of that is, there might be some self-doubt: Am I able to do this thing? I think at some point the gravity of it really set in that once this long five-month trail is over, I have to headline a comedy show, and I’ve never done my own comedy show.”

On Aug. 30, Powers reached Monument 78, the wooden pillar at the Canadian border that marks the official end of the PCT. “I feel like I’m a little kid waking up on Christmas day, and I can’t wait to see this monument, even though it’s just a piece of wood on a border,” he says in a video he filmed of himself walking the last mile. “But it means so much because it signifies the experiences that I’ve had on this trail, both good and bad, that have made me, I believe, a better person.” The video shows one image from every day of his hike, and 19 weeks flash by in a blur of friends, laughter and stunning landscapes. Condensed into two-second snippets, the 136 days look deceptively easy, success predetermined. But the hurdles were legion, and they could be harrowing, as Powers discovered one day near Lake Tahoe.

Threading around a high ridge, he came upon a trail section blocked by ice. Instead of finding a way around, he tried to cross, lost his footing and plunged down the steep chute, glissading out of control across the ice toward exposed rock 150 feet below. He considered himself lucky to survive his fall with only torn clothing and abrasions, not broken bones.

“Everything could have ended in that moment because I made one stupid decision to not take five seconds to assess where I was,” Powers says. “I realized, just because you’re out of the Sierras doesn’t mean the hard part of this hike is over.”

Now, marking the end of the trail at Monument 78, he knew the next big challenge awaited.

“Everyone else is like, ‘The end of the hike! The journey’s over!’ But in my head I knew my journey doesn’t end until I finish these shows.”

On Aug. 31, he hiked back down the trail and headed to Bellingham.

So, a man walks into a bar …

Actually, it’s an old firehouse converted into a performing arts venue, but it does have a bar up front (OK, more of a cafe really) that serves beer and wine.

A man walks into The Firehouse Arts and Events Center, then, where his name is on the marquee, and thinks, “What the hell have I got myself into?”

He’s done a little stand-up—trail shows and five-minute open mics, mostly, a few warmup gigs for Bellingham comics as practice—but he’s never headlined. His parents have flown out from Minnesota to see him perform, and the place is packed with trail friends and curious strangers.

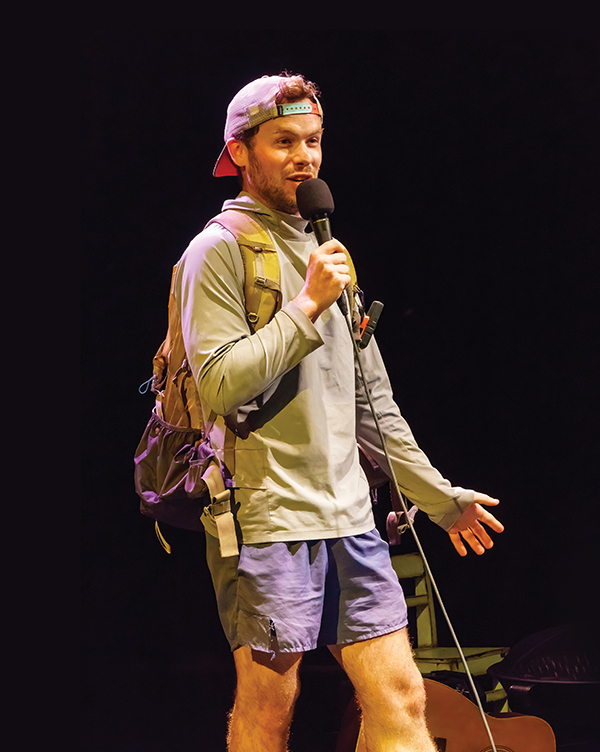

He’s nervous. He’s afraid he’ll forget his lines, and he does. Sometimes he cribs from notecards spread on a stool near a bottle of water emblazoned with his logo (available for $1 at the cafe, he pitches shamelessly). But he rolls with it, even gets a few laughs out of his mistakes. The next night goes even better. He’s more relaxed as he makes fun of jokes that don’t land (“Does this SOS button work in here?” he ad libs, fingering the emergency locator strapped to a backpack he wears while pacing a stage cluttered with hiking gear), his long-suffering parents (“Aren’t there less expensive ways to walk away from your problems, Sean? What about a bowling league?”) and himself and his PCT brethren. (“Thru-hikers are just like sociopaths,” he says, before listing all the hilarious ways this is true. “The difference is sociopaths have no feelings—and thru-hikers won’t shut the @#%! up about them.”)

Who knows if it will play in Peoria, but the Bellingham crowd eats it up. Tonight, that’s enough. As the show ends, a visibly elated Powers thanks his audience and—in a final flourish—throws his notecards in the air.

“It’s fair to say that actually headlining your own show when you have little or no experience as a performer and comedian is in fact a very unusual way to get started,” Rosenfield says, with a wry chuckle. “It is a sign of Sean’s courage, really, because I think most people would be too terrified to even attempt it. The fact that he pulled it off is great.

“He’s an adventurous soul,” the teacher adds, “and I like that.”

“He walked the trail and got to the northern terminus and that was the end of the trail,” Romano says. “But to see him throw all these cards that he’d been working on for five months in the air, to me, that was the real end. ‘I hope you liked my material. I’m done with it. Thanks for coming to the show.’”

But there are more ideas. Always more.

He’s selling an 80-minute special that mixes footage of both Bellingham shows on his website, seanpowerscomedy.com. He’s also working to develop a TV show that would feature him walking the Appalachian Trail in six sections with six comedians, each representing a different style of comedy. (Think “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee,” but with a LOT more commitment asked of the comics.) He hopes to pitch it to Netflix and other networks.

“I’m at a stage where I know that I can learn from anyone from a beginner on up and we could do this together,” he says. “Of course, I’m not going to get Jerry Seinfeld.”

“It’s really ambitious and I have no reason to doubt he will follow through,” Romano says of his friend’s plans. “If he continues on this path of hiking and adventure, along with stand-up, I think he can follow it to the end. So I’m excited to see what he’ll do next. Or maybe he’ll stop doing it altogether. I don’t know.”

Though impressed by his student’s bold spirit, Rosenfield—who’s seen ACI alumni like Jim Gaffigan and Lena Dunham make it big—cautions there are no shortcuts. “In the field of stand-up there is no such thing as an overnight success; there is years and years of apprenticeship,” he says. “Having a pipe dream and actually doing it is kind of terrific. But it’s not a career path.”

Yet Powers has shown promise by a metric Rosenfield values: the laughs-per-minute ratio. Pro level is about four, he explains. During a virtual show for his ACI class, “Sean hit that mark, which was really cool for the first time out,” he says. “So I would say that for the long run, if he ever decided that he actually wants to do this—and I don’t know if that’s the case or not—he’s showing the early signs of being capable if he wishes to.”

To be honest, Powers doesn’t really know either. His Appalachian Trail pitch is a great idea that would be murder to execute. (“I immediately envision a cameraman walking backwards for 2,000 miles,” Romano says.) His mindset might be described as committed, but realistic.

“The best advice I ever got,” Powers says, “is that happiness is the routine, it’s the plan, it’s having the foresight to think about something and execute it from beginning to end and then to go back to regular life.

“But joy is the unexpected. Joy is where adventure comes in. Joy is when the plan falls apart and you start improvising and surprise yourself.”

Learning to walk both paths at once, with a plan for happiness and an openness to adventure, that’s the goal.

“Let’s create something, let’s throw a little drama on this, let’s figure it out,” Powers says. “With both you’ll live a very balanced, happy, fun life.”

The hike is over, but the journey continues. A man walks out of a bar and into the rest of his days.